Everything about this computer is loud: The groan of the power supply is loud. The hum of the cooling fan is loud. The whir of the hard disk is loud. The clack of the mechanical keyboard is loud. It’s so loud I can barely think, the kind of noise I usually associate with an airline cabin: whoom, whoom, whoom, whoom.

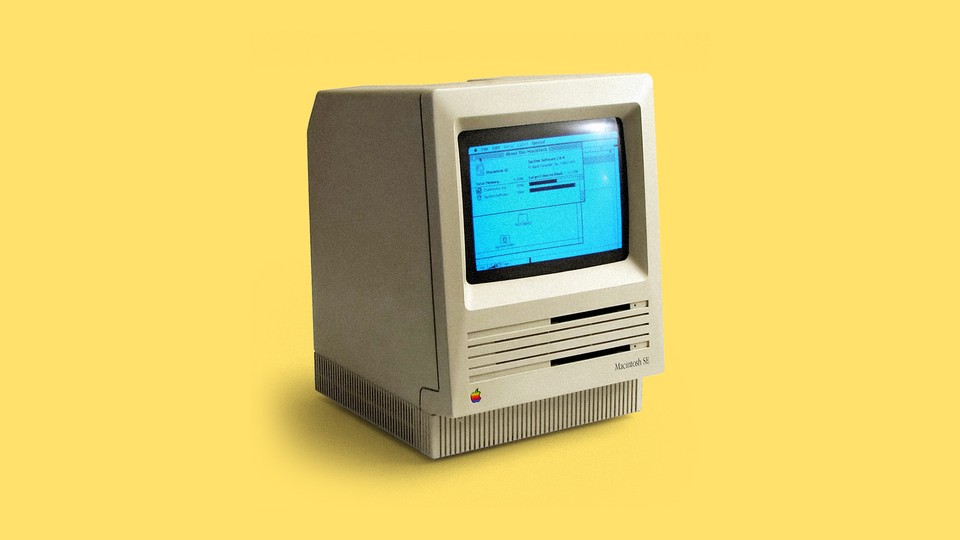

This is the experience a computer user would have had every time she booted up her Macintosh SE, a popular all-in-one computer sold by Apple from 1987 to 1990. By today’s standards the machine is a dinosaur. It boasts a nine-inch black-and-white display. Mine came with a hard disk that offers 20 megabytes of storage, but some lacked even that luxury. And the computer still would have cost a fortune: The version I have retailed for $3,900, or about $8,400 in 2019 dollars.

That’s a lot of money. It’s one of the reasons why computers weren’t as universal three decades ago as they are today, especially at home. In 1984, when the Macintosh first appeared, about 8 percent of U.S. homes had a computer; five years later, when the computer I’m writing on was sold, that figure had risen to a whopping 15 percent.

That made for a totally different relationship to the machine than we have today. Nobody used one every hour—many people wouldn’t boot them up for days at a time if the need didn’t arise. They were modest in power and application, clunking and grinding their way through family-budget spreadsheets, school papers, and games.

A computer was a tool for work, and diversion too, but it was not the best or only way to write a letter or to fritter away an hour. Computing was an accompaniment to life, rather than the sieve through which all ideas and activities must filter. That makes using this 30-year-old device a surprising joy, one worth longing for on behalf of what it was at the time, rather than for the future it inaugurated.

The original Macintosh was an adorable dwarf of a computer. About the size of a full-grown pug, its small footprint, built-in handle, and light weight made it easy to transport and stow. Perched on a single, wide paw, the machine looks perky and attentive, as if it’s there to serve you, rather than you it.

The whirring drone wasn’t an original feature. Steve Jobs insisted on shipping the Macintosh without a cooling fan, to make it run quietly, but by the time this model appeared he had been pushed out of the company, largely on account of how he’d run the Macintosh division. The introduction of Macintosh hard disks in 1985 had ended the machine’s silent service anyway; the SE got one inside the machine, and its smooth bezel was replaced by a more aggressive, vented one: a kind of goblin version of the endearing original.

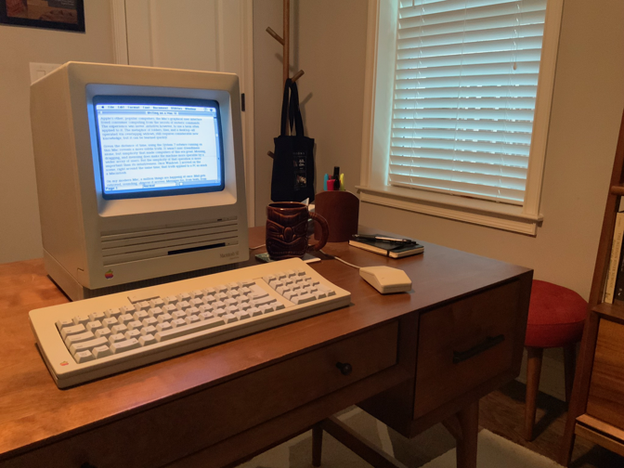

My affection persists, though. I feel comfortable addressing this little machine. Now that laptops are ubiquitous, working on a computer at a desk is an ergonomic misery. At coffee shops and co-working spaces, people hunch over them, staring down toward screens perched at table level. Laptops are even common in offices now, because their portability allows workers to take the job into the field with them—or more likely, to bring it home. Older desktop machines sat monitors higher up, either atop the machine itself, as the Apple II did, or in an all-in-one design, like my Mac SE. The result has me looking directly at the screen, no hunching required.

Then there’s the simplicity. Everyone knows that the great triumph of the Macintosh was its ease of use. Unlike DOS or Unix workstations, and even unlike Apple’s earlier computers, the Mac’s graphical user interface freed consumer computing from esoteric commands. The design was never intuitive, to use a term often applied to it: The metaphor of folders, files, and a desktop, operated via overlapping windows, still required considerable new knowledge, even if that knowledge could be learned quickly. But it wasn’t user-friendliness alone that made computers of this era great—it was simplicity. Mousing, dragging, and menuing does make the machine easier to learn how to use than punching in commands by keystroke. But after that, the plainness of its operation is more important. A 1980s Mac offers only a handful of useful features. (Once Windows 3.0 arrived on the scene, in 1990, that truth applied to a PC as much as a Macintosh.)

On my modern MacBook Pro, a million things are happening at once. Mail retrieves email, sounding regular dings as it arrives. Dispatches fire off, too, in Messages, in Skype, in Slack. Attention-seeking ads flash in the background of web pages, while nagging reminders of Microsoft Office updates bounce in the dock. News notifications spurt out from the screen’s edge, along with every other manner of notices about what’s happening on and off the machine. Computing is a Times Square of urge and stimulus.

By contrast, the Macintosh SE just can’t do much. It boots to a simple file manager, where I face but a few windows and menu options. I can manage files, configure the interface, or run programs. It feels quiet here, despite the whirring noise. At least it’s literal noise, in the ears, instead of the ethereal kind that bombards my faculties on the MacBook Pro.

There aren’t many programs worth running on this old machine, anyway. I installed Pyro, a popular screen saver of the era, and Klondike solitaire, as if I couldn’t distract myself with my iPhone instead. Even within the programs that made people spend money on computers, simplicity reigns. I’m writing in Microsoft Word 4.0, which was released for this platform in 1990. More sophisticated than MacWrite, Apple’s word processor, the program is still extremely basic—the only reason I chose Word was so I could open the file on my modern Mac to edit and file it.

There’s not much to report; it’s a word processor. A window displays the text I am typing, whose fonts and paragraphs I can style in a manner that was still novel in the 1980s. Footnotes, tables, and graphics are possible, but all I really need to do is produce words in order, a cruel reality that has plagued writers for millennia. Any program of this era would have afforded me the important changes computers added: moving an insertion point with the mouse, and seeing the text on-screen in a manner reasonably commensurate with how it would appear in print or online.

In fact, the only feature that’s missing, from a contemporary writer’s perspective, is the capacity to add hyperlinks. That idea had been around for a couple of decades by the time the Macintosh SE came out, but Tim Berners-Lee wouldn’t develop the first web browser until 1989, a year after this computer was manufactured and a year before this copy of Word was released. Of course, it doesn’t matter much, since I can’t go online with this machine (at least, not without adding a modem, and software that wouldn’t become available for another half decade or so).

The many writing tools that today promise to encourage focus and attention are just racing to catch up with a past three decades gone. Programs like WriteRoom and OmmWriter promise a spartan, distraction-free brand of productivity that was just the standard way to write on computers in 1989. Even the keyboard that came with this machine leaves out the extras: No function keys or other extras adorn its surface, which only exists for inputting text. The primitive screen also makes a difference. Today’s internet addicts sometimes set their devices to monochrome to make it less tempting to pick them up. But this Macintosh screen is already black and white, which solidifies its role as a tool for me to use rather than a sink for all my time and attention.

Even the tiny, nine-inch size offers startling benefits. When I wrote about the Freewrite, a portable, hipster word processor that can save files to the cloud, I celebrated the welcome surprise of writing in the world instead of on the computer. That device is flat, with an e-ink screen. In the hands of a touch-typist, it liberates a writer from the sense of being inside the computer, fully enveloped by its overwhelming occupation of your field of vision, and thereby of your attention and ideas. It combats a neglected terror, where what is thinkable only extends as far as what the computer can present.

The all-in-one Macintosh engenders a similar experience. The screen is big enough to see clearly from a foot away, but small enough that it doesn’t overtake my vision. I can look up from it and stare around it, into the distance. Laptops, especially smaller ones, afford something similar, but they also contain the effort of all labors and pleasures; there’s no need, nor desire, ever to look up from one. The Macintosh is portable, handle and all, because it likely would have been put away when its owner wasn’t working on it.

Then, small screens were the norm, first in dedicated word processors, and then in desktop computer monitors, too. The Mac SE’s tiny screen wouldn’t have seemed so tiny back then; even the largest ones were only a few inches bigger. Well into the 1990s, a 17-inch computer monitor would have been heavy and costly, a luxury relegated almost exclusively to professionals.

Even televisions were smaller in this era. A 13-inch TV wouldn’t have been uncommon, and a standard set measured about 25 inches. That made both the television and the computer less prominent in, but more fused with, the home (or work) environment—and, counterintuitively, it did so by receding more into the background. It’s easy to forget a machine’s context of use so long after its equipment has vanished. That history cannot be re-created in software emulation alone. Even when computers became everyday fixtures, they did so away from ordinary life: on out-of-the-way credenzas behind workplace desks or in the covert shadow of basement offices. One would have to go to it, rather than carrying it everywhere. The device was often shared, especially in the home, making it an accessory to life, rather than life itself. It’s hard not to long for that time, given the compulsive draw of constant computing today.

Even bracketing the welcome absence of the internet, with its hurtling notices and demands, the speed of this machine’s operation changes the tenor of my work. Computers used to be slow as hell. When I first got a 386 PC in the early 1990s, I would switch it on and leave the room for a while, so it could load the BIOS, then DOS, then Windows 3.1 atop it—hard disk grinding the whole time—until finally it was ready to respond to my keystrokes and mouse clicks.

The Macintosh SE I’m writing on now boots much faster than Windows ever did, but everything here is slow too. When I open a folder, the file icons all take shape like a color squad entering formation. Loading a program like Word issues a long pause, giving me enough time to view and read the splash screen—a lost software art that provided entertainment as much as feedback. Saving a file grinds the hard disk for noticeable moments, stopping me in my tracks while the cute watch icon spins.

By comparison, today’s machines are lightning-fast. Solid-state drives make boot times and file access almost immediate. Modern multicore processors can access colossal amounts of memory, all the while wasting significant computing power through inefficiency or devoting huge amounts of machine resources to facilitate high-level software development that makes it easier to write programs. Today’s machines power through most simple tasks, such as word processing, by brute force. I don’t even notice booting my modern laptop, running a program, or saving a file anymore. Those acts have evaporated into historical memory, more and more inaccessible even to those, like me, who used the first generations of personal computers often enough to know better. Computers are faster now in every way, but the time that power has captured just gets invested in more computing time.

I glance past the small form of the Macintosh and ponder that idea while this file saves. The drone of the disk and the fan seems to lull into a resonant frequency, with the desk, the chair, and my body and brain connected to them. I wait while my document writes to disk, while Word quits, and while the Mac shuts down. It’s a strange feeling; I can’t remember the last time I shut down a computer, instead of just closing it up or letting it sleep, ready to be reanimated at the touch of a button.

The high-tech industry would characterize that act as an inconvenience, probably, imposed by the primitive technology of the past. Inevitably, in the hands of engineers and investors, the machines were bound to become faster, more powerful, more influential, more ubiquitous. And indeed they did, and now they are everywhere. My laptop is always on; my tablet is ever at the ready; my smartphone is literally in my actual hand except when I’m sleeping, if indeed I ever sleep instead of staring at it.

As I flick off the power switch on the back of the Macintosh, the whine retreats in a gentle diminuendo, until it finally gives way to silence. I have accomplished a feat that is no longer possible: My computing session has ended.