Today’s wander begins at the end because it can in my book of life. And by the end, I think you’ll understand why I made that choice. But don’t scroll ahead cuze then you’ll ruin the surprise.

Our deer friends are feeding on bird seed and corn right now about ten feet from the back door. Meanwhile, the fairies are flittering about behind this doe. Do you see their twinkling wands at work?

Actually, all the lights are kitchen reflections on the door window.

This, of course, has nothing to do with the rest of the day, but I do love our deer friends and like to honor them when I can.

Now on to the nitty gritty of the rest of the story. My friend Dawn and I are Maine Master Naturalists as you may know. And because of that, we must volunteer time to teach others about the natural world. An unpaid job that is hardly a hardship because it’s so much fun.

Right now, we are in the midst of offering a program every other week for Loon Echo Land Trust in Bridgton. And the winter focus is tracking. Not easy to do without snow or mud. Wait a second. The animals are always on the move, and without the snow, we must look for signs. And so we did.

The first, a special offering left on top of a rock that Dawn actually noticed this past weekend when her son and daughter-in-law were visiting, and which she complety embarrassed him by taking photographs of it.

Out came my scat shovel today and everyone took a look. By its form, size, and location, we determined Red Fox.

Our real mission today, however, was to explore the territory of a Red Squirrel. No, this is not my friend Red, but another who has established a territory in a different space that’s also been blessed with an abundant amount of pine cones this year.

We wanted the partipants to take a close look at the scales where the seeds the squirrel sought had been stored. They got right into it.

After locating caches and middens created by said squirrel, we taught the ladies how to use a loupe, aka hand lens, by holding it close to their noses and bringing the object closer until they could focus on it.

To say it opened up a whole new world is possibly an understatement.

Discovering the tiny seeds the squirrel consumes would have been enough, but there was more. In one section of this squirrel’s habitat we found numerous mushrooms upon branches, placed there by the rodent to dry. Talk about being in a food pantry.

And then . . . and then . . . we spotted hoar frost between a couple of stacked logs . . . and surmised that our little friend was living in the space below. How cool is that? Wicked, in these parts of the woods.

What we learned is that this particular squirrel’s territory is located between two downed trees and a wetland, about the size of half a football field.

At the edge of the wetland, it was time to turn our attention from the squirrel to another rodent.

Yes, a Beaver. Once our eyes cued in, just like spotting the squirrel’s mushrooms, beaverworks made themselves known.

And so we encouraged partipants to channel their inner Beaver and try to chop down carrot trees.

Like any Beaver, they were eager to shout, “TIMBER.”

And rejoiced when their tree stumps matched the Beaver’s sculptures.

Finally, we took them along a path that led to more Beaver works, where we noted how its the cambium layer that this rodent seeks for its nutritional value. The rest is left behind, rather like a squirrel’s midden.

And so the inner Beaver channeling continued, this time with pretzel sticks and they were challenged to only remove the outer layer.

The competition was stiff, and a couple of Beavers broke their sticks so we’re not sure they’ll survive the winter.

But at least one was super successful.

While only one Beaver fells a tree, the family may help to break that downed tree into smaller pieces and there are at least three sections like this indicating that they’ve worked on it–maybe one at each spot. We don’t know for sure, but that’s the picture we like to imagine.

Below where we stood, we spotted the dam and talked about construction.

And then located the lodge. Another cool thing–more hoar frost at the top where a vent hole exists and is not covered with the mud that insulates the rest of the structure.

By evidence of the frost, we suspected the family was gathered within, probably consisting of mom and dad, at least two two-year-olds who will move on in the spring, and maybe a few youngsters.

As we walked beside a trail on our way to check out another lodge we determined wasn’t active, one among us discovered a kill site. So here’s the thing. When we first met in the parking lot, that same participant pointed to a Bald Eagle that flew just above the trees.

Could the eagle be the predator of what had been a duck? We suspected so.

The blood was fresh.

Nearby a Mallard had been quaking and we thought it was laughing at us and our enthusiasm and inquisitiveness. But perhaps it was lamenting the loss of a mate. Or at least trying to locate the mate that had become a meal–providing energy for another to carry on.

Yes, it’s sad. But this is nature. This is how it works.

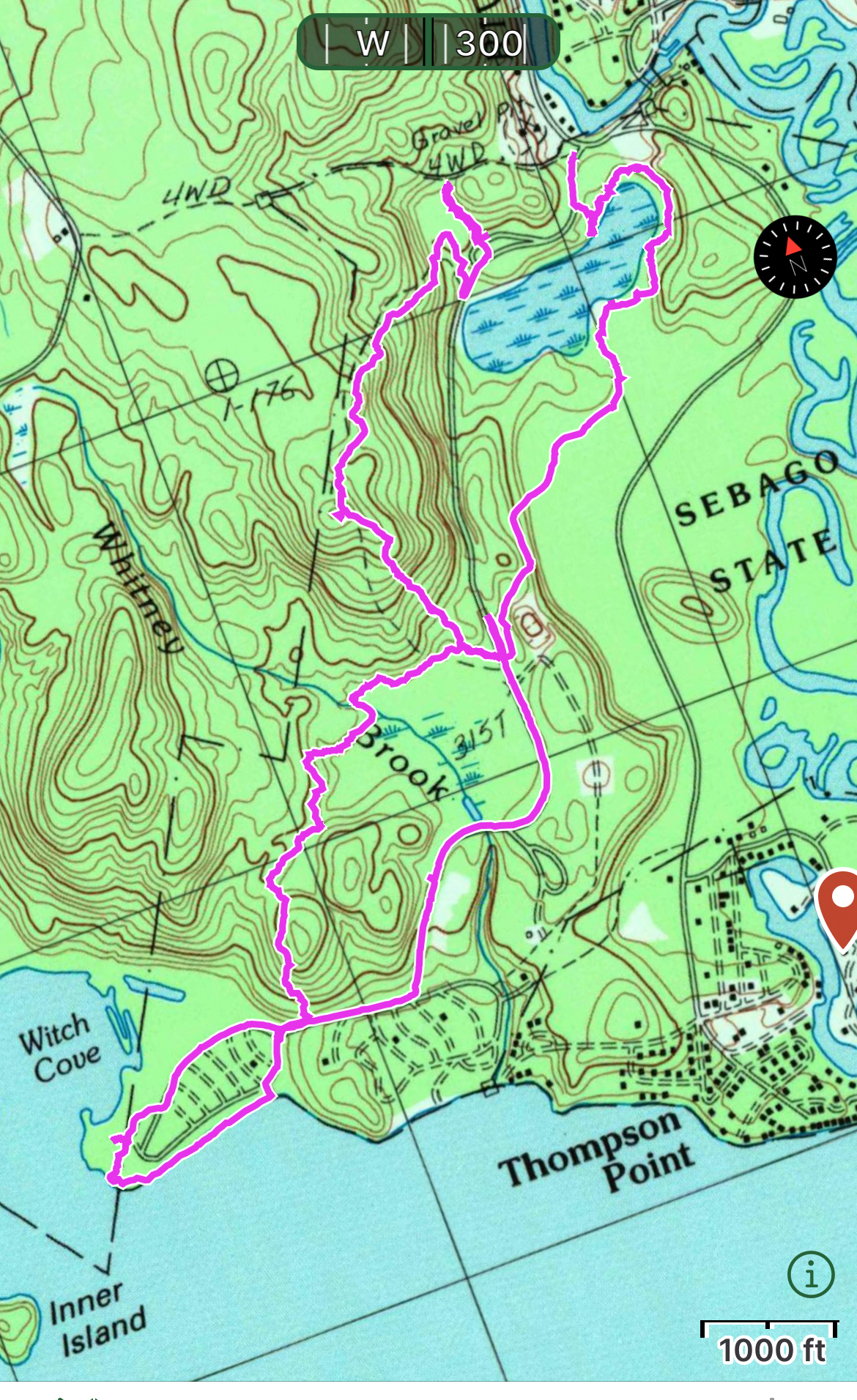

After two delightful hours of discovery and learning, we said goodbye to everyone, dropped in at Loon Echo Land Trust’s office, and then went on a reconnaissance mission at another local spot, trying to determine if we should use it for a class we’ll teach for Lake Region Lifelong Learning, another volunteer venture.

And it was there, that just after we’d talked about being in hare territory and knowing that the lack of snow meant that a hare would stand out amongst the leaves, that . . . Dawn spotted a Snowshoe Hare.

We were so excited about how the morning had unfolded and spying the hare was a grand reward.

Can you track mammals without any snow. YES!

Wednesday Wanders, oh my! So much to learn. So much to share.

You must be logged in to post a comment.