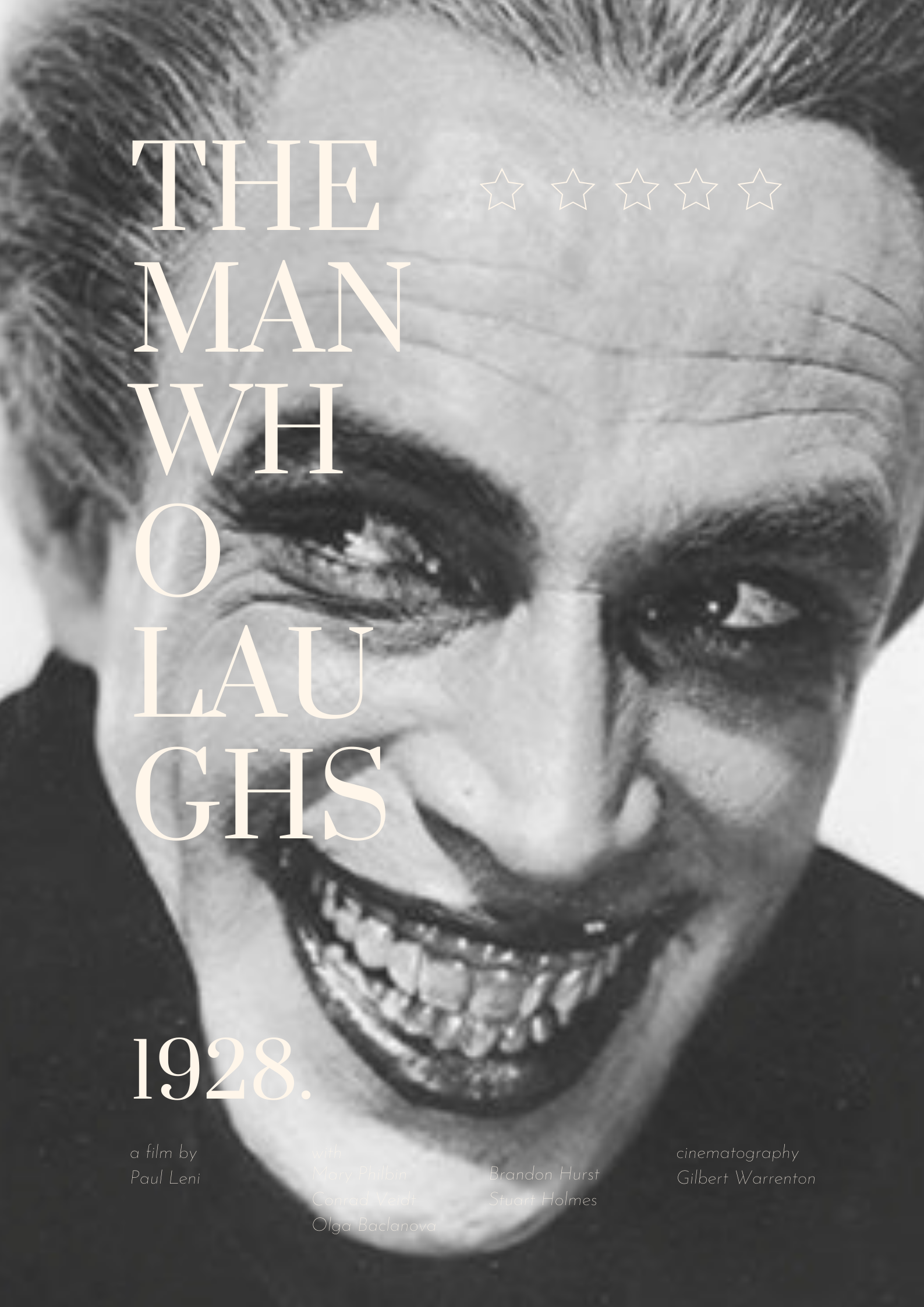

THE MAN WHO LAUGHS: A History and Deconstruction of German Expressionism and Its Application in Modern Culture

“In Gwynplaine’s narrative reality, his external ugliness is both an extension of his physical environment and the demented individuals who inhabit it and a meta-commentary on German Expressionism itself as an artform. In its final dying breath, Leni asserts that German Expressionism, like Gwynplaine, although it is difficult to understand and appreciate, is not ugly . . . Just as Hollywood insisted on creating sterile adaptations of German cultural and filmic identity in order that their films appeal to an American audience, so did the creators of the Joker sterilise the character of Gwynplaine, the incredible work of Paul Leni and Victor Hugo, and German Expressionism in order to create a marketable, easy-to-sell American cultural icon.”

✰✰✰✰✰

Paul Leni’s 1928 film, The Man Who Laughs, based on Victor Hugo’s novel of the same name, is a work which explores and castigates class conflict and caste systems through the conduit of external appearance and internal motivations and sensibilities. Leni delves into this concept especially through the character of Gwynplaine, a man who was disfigured as a child so that he wears a permanent grimace, an expression which is referred to throughout the film as one which laughs, a peculiar and darkly contradictory description for a face belonging to a man who is in constant emotional anguish throughout the overwhelming majority of the film. While Gwynplaine’s face is objectively one that is hideous and uncomfortable to watch, internally, he is gentle, kind, and misunderstood. In this regard, Gwynplaine acts as a foil to those, notably wealthy, characters who externally appear objectively beautiful or normal in comparison, though prove themselves to be internally repulsive in their mistreatment and objectification of Gwynplaine. Through these characterisations, the thesis of The Man Who Laughs becomes clear: externalities in no way reflect who a person truly is in terms of their character. This idea is one which has been revisited and inverted through modern popular culture in the DC comic book character, the Joker, a character born from an image his creators saw of Gwynplaine and on which they modeled his external appearance. Though what is ironic about this fact is that in being inspired by Gwynplaine, the creators of the Joker, a character who is extremely prevalent in the current Zeitgeist, being repeatedly reconsidered and analysed through film and literature, removed totally the nuanced meaning from their source material. The Joker, a flashy character which has surpassed the popularity of Gwynplaine, in both a modern context and considering the time at which The Man Who Laughs was released, is a concept derived from a source which is rarely credited and one which, although at its face appears complex, in comparison to Gwynplaine, is one which is entirely simplistic. While The Man Who Laughs through Gwynplaine explores the cruel nature of humanity and allows its protagonist to suffer because of circumstances that were out of his control and in no way reflect on who he is as an individual, DC’s the Joker simply presents a man who looks to be a monster on the outside, matching who he is on the inside.

In order to fully understand the character of Gwynplaine, a character who not only manifested from the German Expressionist movement but totally embodies it, one must explore the stylistic movement itself. German Expressionism as a style of cinema was introduced by Robert Weine’s 1920 film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The film debuted in Berlin and “was instantly recognized as something new in cinema” (Film History: an Introduction 103). The film proved to be extremely successful and presented to its audience a filmic interpretation of Expressionism, a style “by then well established in most other arts” (Film History 103). In his film, Weine utilised “stylized sets, with strange, distorted buildings painted on canvas backdrops and flats in a theatrical manner” (Film History 103). Additionally, the film introduced a style of acting which became a hallmark of the Expressionist film movement: “[t]he actors made no attempt at realistic performance; instead, they exhibited jerky or dancelike movements” (Film History 103). Mirroring the contemporary Expressionist style of art at the time, those who practised German Expressionism “favored extreme distortion to express an inner emotional reality rather than surface appearances” (Film History 104). In doing so, although it was extremely difficult to recreate in a filmed production, German Expressionist filmmakers drew inspiration from Expressionist painters who “avoided the subtle shadings and colors that gave realistic paintings their sense of volume and depth” (Film History 105). Furthermore, in these works, the human form mirrors its nightmarish surroundings in that “[f]igures might be elongated; faces wore grotesque, anguished expressions and might be livid green” (Film History 105).

The acting style and settings of German Expressionist films specifically referenced the Expressionist movement in theater (Film History 105). In Expressionist theater, “[t]he performances were comparably distorted. Actors shouted, screamed, gestured broadly, and moved in choreographed patterns through the stylized sets” (Film History 105). Considering this, a clear stylistic imperative becomes clear when defining the Expressionist movement: “to express feelings in the most direct and extreme fashion possible” (Film History 105-106).

In film, Expressionism can be defined in multiple ways. Some seek to define German Expressionist films as those works which “resemble The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari in using a distorted, graphic style of mise-en-scène derived from theatrical Expressionism” (Film History 106). Others have determined that the label of Expressionist film is one which is broad, and therefore Expressionist films can be considered as that which “contain some types of stylistic distortion that function in the same ways that the graphic stylization in Caligari does” (Film History 106). Though one aspect of Expressionist films which is crucial to consider is that idea that “the expressivity associated with the human figure extends into every aspect of the mise-en-scène” (Film History 106). This idea is best elaborated using the 1920s definition of Expressionist films as using “sets as ‘acting’ or as blending in with the actors’ movements” (Film History 106). This is a concept on which Conrad Veidt, the actor who played both Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs and Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and therefore not only possessed a nuanced understanding of German Expressionist acting but also helped to create this concept within the film discourse, elaborates in a quote from 1924: “If the decor has been conceived as having the same spiritual state as that which governs the character’s mentality, the actor will find in that decor a valuable aid in composing and living his part. He will blend himself into the represented milieu, and both of them will move in the same rhythm” (Film History 106).

What is important to consider when observing Expressionist acting as a modern viewer is that the acting style “was deliberately exaggerated to match the style of the settings” (Film History 107). In Expressionism, every part of the viewing experience is supposed to feel strange, unfamiliar, and unnatural. The intention in the Expressionist movement was not to create a style which mirrored reality, and therefore Expressionist acting “should be judged not by standards of realism but by how the actors’ behavior contributed to the overall mise-en-scène” (Film History 107). Expressionism aims to explore the ugly and uncomfortable, something which is best exemplified by the fact that “[i]n general, Expressionist actors worked against an effect of natural behavior, often moving jerkily, pausing, and then making sudden gestures” (Film History 107). Although these defining tenants may seem odd or comical to a modern audience, “[b]y the end of the 1910s, Expressionism had gone from being a radical experiment to being a widely accepted, even fashionable, style” (Film History 106). For this reason, even though The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was a critical and commercial success, by the time of its 1920 premiere, its stylistic elements “hardly came as a shock to critics and audiences” (Film History 106). As Weine’s triumph simultaneously proved that Expressionism as a style could be applied to film and laid out a blueprint for other Expressionist filmmakers as to how to create an Expressionist film, after The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, “[o]ther Expressionist films quickly followed” (Film History 106). It is in this context, when Expressionism had become and been an established trend and by the beginning of 1927 was a stylistic movement which had ended, that 1928’s The Man Who Laughs entered the film landscape.

In the 1920s, German films and filmmakers struggled to be respected in Hollywood. At this time, although “German film imports had mightily impressed Hollywood, studio executives had few ideas about what to do with the talent they had acquired except to force them into the same tired genres that Hollywood produced on an assembly line” (Horak 258). What proved to be a difficult style for Hollywood executives to pitch and market to American audiences and film studios also became an impossible landscape for German directors and actors to navigate as well. German creators, though they “attempted to fit into the studio system with varying degrees of success, . . . [they] were often criticized for their ‘European attitudes’ towards subject matter and production methods” (Horak 258). Hollywood’s response to this problem was to make it so that German filmmakers “[m]ainly found themselves directing costume pictures which delivered a particularly American view of old Europe with all its dukes, princesses and cute peasants” (Horak 258). This historical context is one which is immediately apparent as being influential in the creation of The Man Who Laughs when considering its narrative structure, time period, historical setting, and characters. Though what is fascinating about this film is that although it masquerades as an easily digestible and unassuming Hollywood interpretation of what Germany used to be, because it was directed by Paul Leni, who “had filmed such examples of German expressionism as Hintertreppe (Backstairs, 1921) and Das Wachsfigurenkabinett (Waxworks, 1924),” and featured as its protagonist a character played by Conrad Veidt, someone who starred in multiple German Expressionist films, The Man Who Laughs may not only “be viewed as ‘the most relentlessly Germanic film to come out of Hollywood,’” but may be considered more importantly as an act of backlash against a sterile Hollywood adaptation of German cultural and filmic identity, especially an identity as strong and profound as German Expressionism (Conrich 42). The dark and disturbing nature of the narrative and visuals of The Man Who Laughs acts as a cynical and irreverent parody of traditional Hollywood romance films, something which was referenced in its contradictory marketing campaign, where “the artwork for The Man Who Laughs depicts an anguished, and cloaked, Gwynplaine in a clench with Dea, while the pressbook advises the film is ‘the most beautiful love story ever told’” (Conrich 49).

Though what is even more fascinating and sobering about Leni’s film is its spectacular exemplification of poor luck and bad timing. Akin to its protagonist, Gwynplaine, whose life was dramatically altered by unforeseen circumstances, The Man Who Laughs was similarly negatively impacted by situations out of the control of anyone who was involved in the production of the film. Not only did The Man Who Laughs premiere at the end of the public’s fascination with the German Expressionist trend, it also was unable to anticipate the “decisive switch away from silent film to sound, following the impact of the first part-talkie The Jazz Singer (1927)” (Conrich 49). In terms of Universal, the production company which funded The Man Who Laughs, the project proved to be a disastrous failure from a monetary perspective, especially considering the fact that for them, the film was “a significant financial undertaking” (Conrich 48). The nature of the film was one which made American critics and audiences deeply uncomfortable, specifically, “[t]he morbidity of the film was noted by critics, with The Film Spectator, scathing in its review, and declaring ‘there is not a smile in the twelve reels’” (Conrich 51). Even the less caustic reviews expressed derision toward the film, as exemplified by a review of the film published by Picture-Play Magazine, where Norbert Lusk states that The Man Who Laughs “‘has a quality all its own. . . It is bitter, mordant, macabre’” (Conrich 51). The magazine Variety “suggested that ‘The Man Who Laughs will appeal to those who like quasi-morbid plot themes. To others it will seem fairly interesting, [and] a trifle unpleasant’” (Conrich 51). Those more overtly positive reviews “generally applauded the design of the film and the direction of Leni,” something which is apparent in a review of the film by the New York Times, which praised “‘Mr. Leni’s handling of the subject. . . for he revels in light and shadows’” (Conrich 51).

In terms of its overall reception, The Man Who Laughs, at the time of its release, was an outright catastrophe; “it gained poor reviews and despite an apparent ‘appeal to the Lon Chaney mob,’ it was also a commercial failure” (Conrich 51). There are many contributing reasons for this reception that made The Man Who Laughs a film which would not have performed well considering the context in which it was released, reasons which in no way reflect on Leni and Veidt’s brilliant artistry, but rather cripple their efforts. One fault lies with Universal, which had a “lack of an American first-run exhibition circuit- [and] what it had, its small chain of stateside theaters, it had begun to sell off in 1927” (Conrich 51). Another reason for the way Leni’s film was received was that “Universal had invested heavily in a silent film, which had begun preproduction three years prior to cinema’s sound revolution, and by 1928 was soon becoming an anachronism,” making The Man Who Laughs a film which was destined to critically fail even from its beginnings (Conrich 51-52).

Although The Man Who Laughs was a critical failure, in terms of it being an exemplar of German Expressionism, it totally succeeded through its masterful sets and the acting style and appearance of Conrad Veidt as Gwynplaine “to convey not just the pain of human suffering, but also (albeit less than [Victor] Hugo does) to make a strong statement about political corruption and its capacity for atrocity” (Bronski 62).

The sets used throughout The Man Who Laughs totally embody the warped and nightmarish expressivity of German Expressionism, though because they do not replicate the painterly sets of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which feature crooked buildings, jagged windows, and absurdly large furnishings, defining how the sets of The Man Who Laughs embody the German Expressionist movement becomes a difficult endeavor. What further complicates defining the set design in The Man Who Laughs as German Expressionist is that it specifically and overtly references a historical period, which, according to the film, is 17th century England, thereby providing the sets with a familiar cultural and visual frame of reference in that “the extent to which the film’s sets and mise-en-scène aimed to authenticate the period through detailed reproductions, establish it to be a costume drama and a horror-spectacular,” something which was not usually done in German Expressionist films, especially not its defining film, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Conrich 54). Despite this, the way in which Leni creates his sets simultaneously embody and revitalise the German Expressionist style. Instead of solely relying on overt, physical representations of German Expressionism in his sets, Leni marries his set construction with his camera work, making the way in which he frames his set just as important as the physical set design itself. Notably, there are few sets in this film, especially when considering those settings in which Leni’s protagonist, Gwynplaine, is present. Those narrative locations which best represent the way in which Leni manipulates his sets to insert his audience into a hellscape are the castle, Ursus’s traveling home which he shares with both Gwynplaine and Dea, and the traveling circus’s performance stage.

The castle, which looms over actors with which it shares scenes, is a ridiculously enormous and ornately lavish structure which not only acts as a physical representation of one of the film’s themes, that of class disparity and how the upper classes subjugate and humiliate the lower classes for their own amusement, but also embodies the German Expressionist style in its sheer size. The castle is never fully within frame, in either its internal rooms or its external facade, thereby forcing the perspective that it is of unimaginable magnitude. Furthermore, simple set pieces such as doors are also almost never fully in frame; rather, it is implied that their height extends past the limits of the camera’s frame. Conversely, in Ursus’s traveling home, everything appears cramped and diminutive, as both in its framing and set design it appears as though the entirety of the space is able to fit within a medium frame. This not only visually represents the wealth disparity between the characters of Ursus, Dea, and Gwynplaine in comparison to the Duchess Josiana and the Queen, but it also evokes feelings of claustrophobia, representing the idea that Gwynplaine is boxed in in terms of both his physical surroundings and the bleak romantic circumstances which define him as a character for the overwhelming majority of the film. Finally, the setting of Gwynplaine’s performance stage holds significance in regards to German Expressionism when considered in both its contexts: when the stage is filmed from Gwynplaine’s perspective so that the viewer looks out at the audience and when the stage is filmed from the perspective of both the film and the circus audience, so that Gwynplaine is in frame. Both contexts are best exemplified by the sequence at approximately the 00:47:50 mark of the film, where Gwynplaine performs for a crowd which includes the Duchess Josiana. When the fabric covering Gwynplaine’s face is removed, revealing his grotesque grimace, the camera cuts between images of Gwynplaine and the crowd. The crowd is initially framed in medium shots, so that a few laughing faces fill the frame as they, at times, stare into the camera. At approximately the 00:49:00 mark, the boisterous crowd is framed in a medium-long shot, so that nearly the entire room, filled with patrons who laugh at Gwynplaine’s deformity are within view; suddenly, the edges of the frame blur and warp, an effect which spreads over the entirety of the image as a medium-close up image of Josiana, who silently and stoically watches Gwynplaine, bleeds into the frame, merging with the crowd. This framing of Gwynplaine’s perspective of what it is like to inhabit the circus stage is made further horrific when considering it in conjunction with the way Gwynplaine and the stage are framed in this scene. When the stage is within full view, it is framed with the camera at a high and distant perspective, a medium-long shot which shows the square borders of the stage itself and its surrounding, dark walls. From this perspective, Gwynplaine appears to be trapped in a display case which exists only for the amusement of others and for his own torture as Veidt’s eyes scream in pain, directly contrasting the smile plastered on his face as he looks out into the crowd. The camera’s framing, which makes Gwynplaine appear infinitesimally small and trapped by his surroundings and the setting of the stage, with its crudely painted background that further evokes ideas of Gwynplaine’s toy store objectification, together create the sensation that Gwynplaine is unable to escape or live a fulfilling life because of his disfigurement, thereby stylistically blending the distortions of Gwynplaine’s environment with his malformed visage.

German Expressionism is most overtly represented in The Man Who Laughs through Conrad Veidt’s acting style and depiction of Gwynplaine. Throughout the film, Veidt wears an eerie false smile, capable through makeup and Veidt’s own muscular dexterity and tenacity, an experience which he describes in the film’s pressbook: “‘Although my mouth was made-up for Gwynplaine, the laughing clown, my gums especially painted, and false teeth superseded my own, I could not rely on this alone for effect. I could not paint a grin on my face; I had to put it there and keep it there myself. No pretty dancer ever worked harder to learn to kick than I did to grin. But learning to acquire a grin was not as difficult as trying to relax it! After a few months’ work it seemed to be “set” there’” (Conrich 50-51). In his depiction of Gwynplaine, with extremely limited use of his mouth to express the emotions he wished to convey, Veidt nevertheless manages to evoke profound and heart-wrenching emotions through the use of his eyes and his body, constantly pulling at and contorting the upper regions of his face and his entire figure to depict the inner turmoil essential to Gwynplaine’s characterisation. This idea is best exemplified at two deeply profound moments in the film: that moment at approximately the 00:52:00 mark of the film, where a clown tells Gwynplaine that he is lucky that he does not have to wash off his smile, and that sequence at approximately the 1:00:00 mark of the film, where Duchess Josiana attempts to force herself on Gwynplaine. In the former scene, in response to the clown’s statement, as the camera frames him in a close-up shot, Veidt creatively finds a way around his inability to move his mouth; seeing as he cannot move his lips out of a cold and exhausted smile, Veidt softens his eyes as he pulls at his bottom lip, further distorting his face into an even more harrowing and yet, simultaneously depressing expression. In the latter sequence, Veidt utilises every part of his body, making the interaction between himself and Olga Baclanova even more unbearable to watch. As Gwynplaine struggles against Josiana as she attempts to pull him on top of her, Veidt covers his mouth with one sleeve while expressing a manic fear with his wide and darting eyes; when he removes his arm from his mouth, he retracts it, as if it were broken, his claw-like hand slithering back into the recesses of his black cloak as his back arches as if he were a frightened feline.

As Mario Rodriguez states in his essay, “Physiognomy and Freakery: The Joker on Film,” “Veidt had a face well suited to these tormented dreamscapes: ‘His lanky figure, his angular facial features perfectly suited the nightmarish aesthetic of expressionism’” (“Physiognomy and Freakery”). Though what is crucial to consider is the way in which Leni both takes advantage of and subverts his audience’s revulsion towards Gwynplaine’s appearance: while Conrad Veidt’s contortion and distortion of his body and face creates in Gwynplaine a character who is terrifying externally, this is something which in no way reflects on who he is internally. As a character, Gwynplaine’s external ugliness acts as a mask which conceals his true nature, that of a kind and gentle soul. Through Leni’s framing of the way the majority of characters within the film react to Gwynplaine’s externalities, by laughing at him or treating him as a fetish object, he not only reveals the internal ugliness within the characters who externally appear normal in comparison to Gwynplaine, but he also makes a commentary on human nature and people’s ability to easily categorise or judge someone based on shallow externalities.

To both Paul Leni and Victor Hugo, ugliness is terrifying when it is hidden, when it cannot be read on someone’s face. Even though Dea, who falls in love with Gwynplaine as she is blind and cannot see his face, could be argued as a character who negates this thesis as in her inability to see Gwynplaine, she sees him through a symbolic mask derived from her imagination and blindness, in actuality, she strongly supports the idea that Leni and Hugo believe the most insidious form of repulsiveness is one that cannot be immediately seen on someone’s face. In her purity and innocence, Dea as a character embodies the ultimate non-judgemental individual, the type of person Leni and Hugo wish could be more prevalent in humanity: someone who does not judge a person for who they are internally because of how they appear externally.

It is this message which Bob Kane, Jerry Robinson, and Bill Finger, the creators of the Joker character, completely and totally neglected to acknowledge when taking inspiration from Gwynplaine. Ironically, in adopting only Gwynplaine’s external appearance and using it as the face of a character who is inherently and totally evil, thereby disregarding who Gwynplaine truly was as a character, they represent the type of people for whom Leni and Hugo express disdain. In removing Gwynplaine’s face from its context, the creators of the Joker either never cared to delve into their source material or they explored their source material and decided regardless to strip it entirely of its meaning. Though whatever the underlying reasoning for Kane, Finger, and Robinson’s decision, their refusal to acknowledge the true source of their inspiration is something insidiously plagiaristic and helps one to understand why, at its core, the character and purpose of the Joker is empty when compared to its source material, Gwynplaine.

The true source of Kane, Finger, and Robinson’s inspiration for the Joker is a fact which is difficult to discover, though upon extended research, one will discover that “Kane and Robinson agree that Finger handed Kane a photograph of Conrad Veidt from the 1928 film adaptation of Victor Hugo’s The Man Who Laughs. A clown-faced ad for a Coney Island attraction has received some credit too. But Finger kept his primary source a secret” (“Thou Shalt Not Kill” 191). Entirely unlike Gwynplaine, the Joker is a character who represents the absolute worst of humanity, so much so that in filmic and comic book narratives which feature him, characters such as Batman in the 2008 film, The Dark Knight, often neglect to refer to the Joker as an individual or human being, but rather as an entity of evil or simply as “garbage,” a label which is fitting considering that just in Alan Moore’s graphic novel, A Killing Joke, the Joker “rigs a funhouse ride to project photos of Commissioner Gordon’s raped and crippled daughter” (“Thou Shalt Not Kill” 183).

What is fascinating about both the Joker and Gwynplaine as characters is that in their characterisations, they both engage in the deconstruction of the idea of the joke, a feat undertaken by Hugo in many of his works, and the deconstruction of the idea of repulsiveness. Victor Hugo is notable as a writer because there exist “few other nineteenth-century writers who refer to laughter as frequently” (Moore 134). Something which is notable in terms of who Hugo is as a writer, Leni’s characterisation of Gwynplaine, and the multiple interpretations of the Joker character is that there is a common thread which runs through all of their works: they all, whether intentionally or unintentionally, reference the fact that while Hugo “understood something about the infantile personality of a crowd, which is apt to laugh like an enormous overgrown child,” he simultaneously understood the inverse and dark side of laughter, exemplified in his capability to “describe a laugh that was a horrible deformity” and his emphasising in his works of “the sadistic laughter of the mob” (Moore 152). Taking these aspects of Hugo’s writing into consideration, one is able to draw a more clear distinction between the characterisations of Gwynplaine and the Joker. Gwynplaine’s character is one which is tragic because he bears the brunt of the joke; he is unable to join in on the laughter of everyone else, those people who laugh at his expense, and his disfigured smile is an incessant and darkly sarcastic reminder of the fact that he will always be the joke which produces degrading laughter, rather than join in on the joke. On the other hand, the Joker, through his sadistic temperament, aims to make life and everyone else the joke, a joke which will always result in the suffering of others. While Gwynplaine in Leni’s narrative is never allowed to participate in the joke, the Joker creates the jokes, albeit those which are in no way humorous. In this regard, the Joker, though he externally resembles Gwynplaine, more closely represents the crowd and those upper class individuals who mock and jeer at Gwynplaine for his deformities. Just as those people who laugh at Gwynplaine find agony to be humorous, so does the Joker.

In both of their characterisations, Gwynplaine and the Joker are similar in that they aim to deconstruct the very idea of the joke, the idea that “[t]he unmasking function of joking consists mostly of the fact that a socially accepted or traditional meaning structure is exposed to a totally different meaning structure and that the former is looked at through the eyes of the latter” (Zijderveld 304). When considering both Gwynplaine and the Joker as characters, they are both deeply unfunny even though they carry the label of “clown.” In dissecting these characters, there is no laughter or fun to be had and there is no joke to be enjoyed. Though where the two characters diverge is in how the jokes are made and who makes them at whose expense and the narrative environments in which the two characters exist. In Gwynplaine’s narrative reality, his external ugliness is both an extension of his physical environment and the demented individuals who inhabit it and a meta-commentary on German Expressionism itself as an artform. In its final dying breath, Leni asserts that German Expressionism, like Gwynplaine, although it is difficult to understand and appreciate, is not ugly. Conversely, the Joker exists as a stark contrast to his environment of the realistic cityscape of Gotham, a representation of New York City, and the mostly good people who inhabit it. The Joker’s outrageous and frightening appearance stands out from his setting whereas Gwynplaine’s visage blends into his environment. As Gwynplaine is an extension of his freakish environment, when people in his world express aversion towards him, it comes across as cruel, considering that he is a natural derivation of the world in which they live, making their non-acceptance of him a rejection of the obvious ugliness of their world whereas the Joker is simply ugliness which society thought had been discarded, but instead persists. It is this persistence of the Joker as a character, both within his comic book universe and in the cultural Zeitgeist, where a parallel may be drawn to the context in which The Man Who Laughs was born. Just as Hollywood insisted on creating sterile adaptations of German cultural and filmic identity in order that their films appeal to an American audience, so did the creators of the Joker sterilise the character of Gwynplaine, the incredible work of Paul Leni and Victor Hugo, and German Expressionism in order to create a marketable, easy-to-sell American cultural icon.

Bibliography

Bronski, Michael. Cinéaste, vol. 33, no. 2, 2008, pp. 61–63.

JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41690638.

Conrich, Ian. “Before Sound: Universal, Silent Cinema, and the

Last of the Horror-Spectaculars.” The Horror Film, edited by Stephen Prince, Rutgers University Press, 2004, pp. 40–57. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hj2bp.5.

Horak, Jan-Christopher. “Sauerkraut & Sausages with a Little

Goulash: Germans in Hollywood, 1927.” Film History, vol. 17, no. 2/3, 2005, pp. 241–260. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3815594.

Leni, Paul, director. The Man Who Laughs. 1928.

Moore, Olin H. “Victor Hugo as a Humorist before 1840.” PMLA,

vol. 65, no. 2, 1950, pp. 133–153. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/459460.

Rodriguez, Mario. “Physiognomy and Freakery: The Joker on

Film.” Americana: The Journal of American Popular Culture, vol. 13, no. 2, 2014, doi:http://www.americanpopularculture.com/journal/articles/fall_2014/rodriguez.htm.

Thompson, Kristin, and David Bordwell. Film History: an

Introduction. 2nd ed., McGraw-Hill Education, 2002.

“Thou Shalt Not Kill.” On the Origin of Superheroes: From the Big

Bang to Action Comics No. 1, by Chris Gavaler, University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, 2015, pp. 165–202. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt20p57k9.9.

Zijderveld, Anton C. “Jokes and Their Relation to Social Reality.”

Social Research, vol. 35, no. 2, 1968, pp. 286–311. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40969908.