the autolytic debridement of venous leg ulcers - Wounds International

the autolytic debridement of venous leg ulcers - Wounds International

the autolytic debridement of venous leg ulcers - Wounds International

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Technical Guide<br />

THE AUTOLYTIC DEBRIDEMENT<br />

OF VENOUS LEG ULCERS<br />

Deborah H<strong>of</strong>man is Clinical Nurse Specialist in Wound Healing, Department <strong>of</strong> Dermatology, Churchill Hospital, Oxford<br />

Wound <strong>debridement</strong> is part <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wound healing process which may occur without intervention but,<br />

more <strong>of</strong>ten, assistance is needed. It is important to recognise <strong>the</strong> situations when <strong>debridement</strong> is not<br />

appropriate. This article will describe how to recognise dead tissue that should be removed from <strong>the</strong><br />

wound, when <strong>debridement</strong> should not be attempted and <strong>the</strong> various methods that can be used.<br />

Debridement describes any<br />

method that facilitates <strong>the</strong><br />

removal <strong>of</strong> dead (necrotic) tissue,<br />

cell debris or foreign bodies from<br />

a wound (O’Brien, 2003). It is<br />

regarded as an essential part<br />

<strong>of</strong> wound bed preparation, as<br />

it enhances <strong>the</strong> potential for a<br />

wound to heal. Dead tissue in<br />

<strong>the</strong> wound not only physically<br />

prevents <strong>the</strong> wound from<br />

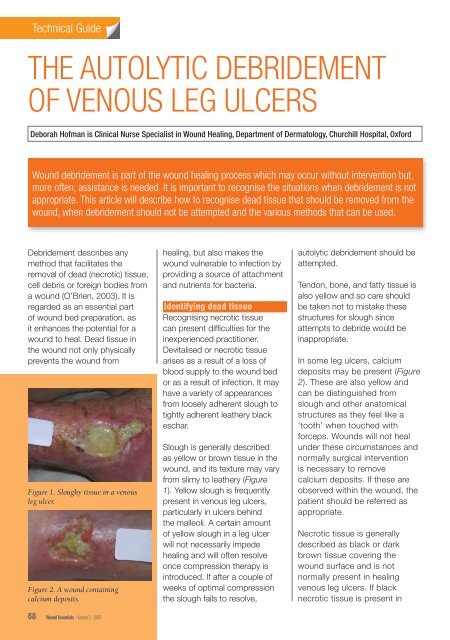

Figure 1. Sloughy tissue in a <strong>venous</strong><br />

<strong>leg</strong> ulcer.<br />

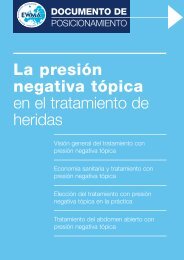

Figure 2. A wound containing<br />

calcium deposits.<br />

68 Wound Essentials • Volume 2 • 2007<br />

healing, but also makes <strong>the</strong><br />

wound vulnerable to infection by<br />

providing a source <strong>of</strong> attachment<br />

and nutrients for bacteria.<br />

Identifying dead tissue<br />

Recognising necrotic tissue<br />

can present diffi culties for <strong>the</strong><br />

inexperienced practitioner.<br />

Devitalised or necrotic tissue<br />

arises as a result <strong>of</strong> a loss <strong>of</strong><br />

blood supply to <strong>the</strong> wound bed<br />

or as a result <strong>of</strong> infection. It may<br />

have a variety <strong>of</strong> appearances<br />

from loosely adherent slough to<br />

tightly adherent lea<strong>the</strong>ry black<br />

eschar.<br />

Slough is generally described<br />

as yellow or brown tissue in <strong>the</strong><br />

wound, and its texture may vary<br />

from slimy to lea<strong>the</strong>ry (Figure<br />

1). Yellow slough is frequently<br />

present in <strong>venous</strong> <strong>leg</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>,<br />

particularly in <strong>ulcers</strong> behind<br />

<strong>the</strong> malleoli. A certain amount<br />

<strong>of</strong> yellow slough in a <strong>leg</strong> ulcer<br />

will not necessarily impede<br />

healing and will <strong>of</strong>ten resolve<br />

once compression <strong>the</strong>rapy is<br />

introduced. If after a couple <strong>of</strong><br />

weeks <strong>of</strong> optimal compression<br />

<strong>the</strong> slough fails to resolve,<br />

<strong>autolytic</strong> <strong>debridement</strong> should be<br />

attempted.<br />

Tendon, bone, and fatty tissue is<br />

also yellow and so care should<br />

be taken not to mistake <strong>the</strong>se<br />

structures for slough since<br />

attempts to debride would be<br />

inappropriate.<br />

In some <strong>leg</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>, calcium<br />

deposits may be present (Figure<br />

2). These are also yellow and<br />

can be distinguished from<br />

slough and o<strong>the</strong>r anatomical<br />

structures as <strong>the</strong>y feel like a<br />

‘tooth’ when touched with<br />

forceps. <strong>Wounds</strong> will not heal<br />

under <strong>the</strong>se circumstances and<br />

normally surgical intervention<br />

is necessary to remove<br />

calcium deposits. If <strong>the</strong>se are<br />

observed within <strong>the</strong> wound, <strong>the</strong><br />

patient should be referred as<br />

appropriate.<br />

Necrotic tissue is generally<br />

described as black or dark<br />

brown tissue covering <strong>the</strong><br />

wound surface and is not<br />

normally present in healing<br />

<strong>venous</strong> <strong>leg</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. If black<br />

necrotic tissue is present in

Technical Guide<br />

a <strong>leg</strong> ulcer, o<strong>the</strong>r causes <strong>of</strong><br />

ulceration should be looked<br />

for, e.g. ischaemia (Figure 3),<br />

in which case urgent referral<br />

to a vascular unit should<br />

be instigated. Pyoderma<br />

gangrenosum and vasculitis are<br />

relatively rare conditions which<br />

cause <strong>leg</strong> ulceration and <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

cause necrosis. In patients<br />

with vasculitis, <strong>the</strong>re are usually<br />

mulitple lesions present (Figure<br />

4). Pyoderma gangrenosum<br />

usually presents as a rapidly<br />

enlarging, very painful lesion<br />

with necrosis and typically <strong>the</strong>re<br />

is undermining at <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

edges (Figure 5). Patients where<br />

<strong>the</strong>se conditions are suspected<br />

should undergo urgent referral<br />

to a dermatologist.<br />

Slough which is heavily<br />

colonised with anaerobic<br />

bacteria is also <strong>of</strong>ten black.<br />

However, this is usually slimy,<br />

as opposed to <strong>the</strong> dry lea<strong>the</strong>ry<br />

texture <strong>of</strong> necrotic tissue, and<br />

can be effectively managed<br />

with topical metronidazole.<br />

Topical metronidazole can be<br />

used safely on wounds for<br />

up to six weeks. There is no<br />

known risk <strong>of</strong> resistance or<br />

contact sensitivity. However, in<br />

patients who are taking warfarin,<br />

it should be used with care<br />

as it affects <strong>the</strong> international<br />

normalised ratio (INR).<br />

Dried blood on <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

surface is also black and may<br />

be difficult to distinguish from<br />

necrotic tissue.<br />

It is important to be able to<br />

recognise and describe different<br />

types <strong>of</strong> tissue and to know<br />

when to leave well alone. If in<br />

doubt specialist help should<br />

always be sought.<br />

70 Wound Essentials • Volume 2 • 2007<br />

Figure 3. Necrotic tissue in ulcer with significant arterial insufficiency.<br />

Figure 4. Vasculitis.<br />

Figure 5. Pyoderma gangrenosum.<br />

Selecting a method<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>debridement</strong><br />

The selection <strong>of</strong> a method<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>debridement</strong> depends on<br />

<strong>the</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> product,<br />

local expertise and patient<br />

preference.<br />

There are a number <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>debridement</strong> techniques used by

healthcare pr<strong>of</strong>essionals, and<br />

<strong>the</strong>y can be categorised into:<br />

8Active <strong>debridement</strong><br />

8Autolytic <strong>debridement</strong> (ei<strong>the</strong>r<br />

moisture donating or moisture<br />

absorbing).<br />

Active <strong>debridement</strong><br />

Surgical <strong>debridement</strong><br />

Surgical <strong>debridement</strong> involves<br />

<strong>the</strong> removal <strong>of</strong> dead tissue from<br />

<strong>the</strong> wound bed. It is carried out<br />

under surgical conditions and<br />

results in a bleeding wound bed<br />

as a result <strong>of</strong> complete removal <strong>of</strong><br />

necrotic material. This is carried<br />

out by surgeons, podiatrists and<br />

specialist nurses who have been<br />

trained in <strong>the</strong> procedure, using<br />

scalpel and forceps.<br />

Sharp <strong>debridement</strong><br />

Sharp <strong>debridement</strong> is <strong>the</strong> removal<br />

<strong>of</strong> dead tissue with scissors<br />

or scalpel. This should only<br />

be carried out by a healthcare<br />

pr<strong>of</strong>essional who has been<br />

trained in <strong>the</strong> procedure.<br />

Larval <strong>the</strong>rapy<br />

Larvae or maggots have been<br />

used in <strong>the</strong> UK to debride<br />

wounds for at least 10 years<br />

and are a fast, effective and<br />

safe method <strong>of</strong> <strong>debridement</strong><br />

(Thomas, 1998). Maggots are<br />

now available ei<strong>the</strong>r as ‘freerange’<br />

(and placed directly into<br />

<strong>the</strong> wound) or contained in<br />

bags. The powerful enzymes<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir saliva dissolve necrotic<br />

tissue, which <strong>the</strong> maggots <strong>the</strong>n<br />

ingest. They do not have to be<br />

in direct contact with <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

bed. However, free-range<br />

maggots have <strong>the</strong> advantage<br />

<strong>of</strong> being able to penetrate<br />

crevices and sinuses more<br />

effectively. The disadvantage is<br />

that <strong>the</strong>y can escape and cause<br />

distress to both patient and<br />

practitioner. A detailed guide to<br />

larval <strong>the</strong>rapy can be found on<br />

p.156–9.<br />

Enzymatic<br />

There are various enzyme<br />

preparations which are effective<br />

at digesting dead tissue, e.g.<br />

collagenase and papaina, but<br />

<strong>the</strong>se are not currently available<br />

in <strong>the</strong> UK (Bellingeri and H<strong>of</strong>man,<br />

2006).<br />

Autolytic <strong>debridement</strong><br />

Autolytic <strong>debridement</strong> is <strong>the</strong><br />

process by which <strong>the</strong> body<br />

attempts to shed devitalised<br />

tissue by <strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> moisture.<br />

Where tissue can be kept moist,<br />

it will naturally degrade and<br />

deslough from <strong>the</strong> underlying<br />

healthy structures. This process<br />

is helped by <strong>the</strong> presence<br />

<strong>of</strong> enzymes called matrix<br />

metalloproteinases (MMPs),<br />

which are produced by damaged<br />

tissue and which disrupt <strong>the</strong><br />

proteins that bind <strong>the</strong> dead tissue<br />

to <strong>the</strong> body. This process can<br />

be enhanced by <strong>the</strong> application<br />

<strong>of</strong> wound management<br />

products which promote a moist<br />

environment. These products can<br />

be divided into two categories:<br />

those that donate moisture<br />

to <strong>the</strong> dead tissue and those<br />

that absorb excess moisture<br />

produced by <strong>the</strong> body. Both are<br />

designed to facilitate <strong>the</strong> <strong>autolytic</strong><br />

<strong>debridement</strong> process (Gray et al,<br />

2005).<br />

Moisture donation<br />

Hydrocolloids and hydrogels<br />

(amorphous gel in a tube or<br />

hydrogel sheets), donate moisture<br />

to <strong>the</strong> dead tissue to facilitate<br />

<strong>autolytic</strong> <strong>debridement</strong>.These<br />

dressings are particularly useful<br />

in wounds that are not heavily<br />

exuding (Tip 1).<br />

Technical Guide<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> a second generation<br />

hydrogel sheet, e.g. Actiform<br />

Cool ® , will absorb a certain<br />

amount <strong>of</strong> moisture while<br />

donating it so, in many cases,<br />

will provide a good moisture<br />

balance at <strong>the</strong> wound surface.<br />

If desired <strong>the</strong> dressing can be<br />

cut to fit <strong>the</strong> wound (Tip 2). The<br />

white backing should be peeled<br />

<strong>of</strong>f and <strong>the</strong> dressing laid gel side<br />

down on to <strong>the</strong> wound surface.<br />

Dressings should be changed<br />

when <strong>the</strong>re is strikethrough, but<br />

may be left on for up to seven<br />

days if <strong>the</strong>re is no leakage. A<br />

second generation hydrogel sheet<br />

dressing may continue to be used<br />

after <strong>debridement</strong> has occurred<br />

through to healing as it promotes<br />

granulation tissue and maintains a<br />

clean wound bed (Figures 6,7,8,9).<br />

Moisture absorption<br />

Alginates, cellulose dressings and<br />

foams are designed to absorb<br />

exudate. By absorbing excess<br />

wound fluid, <strong>the</strong>se products<br />

avoid damage to <strong>the</strong> surrounding<br />

skin from maceration (Tip 3).The<br />

structure <strong>of</strong> some foam dressings<br />

alters under compression so that<br />

<strong>the</strong> moisture remains in contact<br />

with <strong>the</strong> skin. Care should be<br />

taken <strong>the</strong>refore to select an<br />

appropriate foam. These dressings<br />

Tip 1<br />

8A common error is to apply<br />

a hydrogel to a wet wound<br />

that contains some slough<br />

in an attempt to debride <strong>the</strong><br />

wound. It is more important<br />

to get <strong>the</strong> moisture balance<br />

right than to remove <strong>the</strong><br />

sloughy tissue which will<br />

resolve itself in <strong>the</strong> right<br />

environment.<br />

Wound Essentials • Volume 2 • 2007 71

Technical Guide<br />

Figure 6. Slough is present on <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

bed before application <strong>of</strong> dressing.<br />

Figure 7. Remove <strong>the</strong> backing from <strong>the</strong><br />

hydrogel sheet and place gel side down<br />

on <strong>the</strong> wound.<br />

Figure 8. A clean wound bed on removal<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> dressing.<br />

Figure 9. Once <strong>debridement</strong> has<br />

occurred, <strong>the</strong> dressing can be continued<br />

to promote granulation.<br />

should not be used on a dry<br />

sloughy wound as <strong>the</strong>y will fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

dry out <strong>the</strong> tissue, making it more<br />

adherent and painful.<br />

Dressings which reduce <strong>the</strong><br />

bacterial burden <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

A heavy bacterial burden in<br />

a wound will encourage tissue<br />

72 Wound Essentials • Volume 2 • 2007<br />

degradation and slough formation.<br />

Dressings which reduce bacteria in<br />

a wound such as honey, silver, or<br />

cleansing fluid such as Prontosan ®<br />

(Horrocks, 2006), may help to<br />

reduce slough and promote healthy<br />

granulation.<br />

The process <strong>of</strong> <strong>debridement</strong><br />

will increase exudate and this in<br />

turn may damage surrounding<br />

skin. The frequency <strong>of</strong> dressing<br />

change may have to be<br />

increased and surrounding<br />

skin protected with a suitable<br />

barrier such as Cavilon cream/<br />

ointment (3M Health Care) or<br />

zinc paste. Dressings which<br />

donate moisture (such as<br />

hydrogels) should not be used<br />

on a wet wound as <strong>the</strong> increase<br />

in moisture will macerate <strong>the</strong><br />

skin. Honey dressings, although<br />

increasing exudate in <strong>the</strong> initial<br />

phase, will, by reducing bacterial<br />

load, also eventually reduce<br />

exudate.<br />

The choice <strong>of</strong> method <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>debridement</strong> depends on wound<br />

severity and patient preference.<br />

Many patients like <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> a<br />

natural product such as honey. The<br />

only reason to avoid this dressing<br />

would be pain as patients <strong>of</strong>ten find<br />

<strong>the</strong> drawing sensation intolerable.<br />

Maggot treatment is more rapid<br />

than <strong>autolytic</strong> <strong>debridement</strong> and if<br />

<strong>the</strong> wound is very <strong>of</strong>fensive and<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a lot <strong>of</strong> sloughy/necrotic<br />

tissue <strong>the</strong> larval <strong>the</strong>rapy should<br />

be considered.<br />

If <strong>the</strong> wound is very painful it is<br />

unlikely that maggot treatment will<br />

be tolerated, and some patients<br />

are repelled by <strong>the</strong> idea <strong>of</strong> larval<br />

<strong>the</strong>rapy. In a painful wound,<br />

<strong>the</strong> use <strong>of</strong> a second generation<br />

hydrogel sheet should be<br />

considered.<br />

Common misconceptions<br />

8Practitioners are rightly<br />

taught that <strong>debridement</strong> is an<br />

essential part <strong>of</strong> wound healing.<br />

However, dressings which are<br />

marketed as having a debriding<br />

action, e.g. hydrogels, are <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

applied inappropriately without<br />

consideration <strong>of</strong> moisture<br />

balance. This can result in<br />

maceration.<br />

8In an attempt to debride<br />

wounds on wet <strong>leg</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>,<br />

<strong>the</strong> healthcare pr<strong>of</strong>essional<br />

<strong>of</strong>ten uses a combination <strong>of</strong><br />

dressings which are <strong>the</strong>reby<br />

rendered ineffective, e.g.<br />

hydrogels (moisture donating)<br />

and alginates (moisture<br />

absorbing) or hydrogels and<br />

foams (moisture absorbing). A<br />

combination <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se dressings<br />

results in a ‘sludge’ which has<br />

no debriding effect.<br />

Where <strong>the</strong> wound is very<br />

wet <strong>the</strong> practitioner should<br />

attempt to identify <strong>the</strong><br />

Tip 2<br />

8Patients should be warned<br />

that <strong>the</strong> constituency <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> second generation<br />

hydrogel sheet dressing will<br />

change and <strong>the</strong>re may be<br />

an unpleasant odour. This<br />

is also true <strong>of</strong> hydrocolloid<br />

dressings.<br />

Tip 3<br />

8Capillary action dressings or<br />

those with a super absorbent<br />

capability may be useful in<br />

<strong>the</strong> management <strong>of</strong> very wet<br />

sloughy wounds.

cause and address moisture<br />

balance before considering<br />

<strong>debridement</strong>. Possible causes<br />

<strong>of</strong> wetness include:<br />

1. Heavy bacterial burden: Does<br />

<strong>the</strong> patient need systemic<br />

antibiotics and/or topical<br />

antibacterial management (e.g.<br />

honey, silver, iodine)?<br />

2. Wet eczema: does <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

need referral to a specialist<br />

nurse or dermatologist?<br />

Topical steroid <strong>the</strong>rapy may be<br />

needed.<br />

2. Oedema: Is <strong>the</strong> patient<br />

receiving adequate<br />

compression? Are <strong>the</strong>y<br />

elevating <strong>the</strong>ir <strong>leg</strong>s sufficiently?<br />

Have <strong>the</strong>y been taught<br />

dorsiflexion exercises to reduce<br />

oedema?<br />

3. Is <strong>the</strong> dressing sufficiently<br />

absorbent? Dressings within<br />

<strong>the</strong> same category perform<br />

differently, e.g. foams. Some<br />

will remove <strong>the</strong> exudate<br />

from <strong>the</strong> wound, but o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

keep <strong>the</strong> exudate next to<br />

<strong>the</strong> skin causing fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

tissue damage. Many foams<br />

do not perform well under<br />

compression. Alginates and<br />

cellulose (Aquacel ®, ConvaTec)<br />

dressings can be beneficial. If<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is heavy pseudomonal<br />

exudate, which has a<br />

characteristic bright green<br />

colour, dressings containing<br />

silver may be helpful.<br />

When is debriding a <strong>venous</strong> <strong>leg</strong><br />

ulcer not appropriate?<br />

1. Arterial <strong>ulcers</strong> should not<br />

normally be debrided (Leaper,<br />

2002). If <strong>the</strong>re is a poor blood<br />

supply to <strong>the</strong> limb, it is best to<br />

keep a necrotic wound dry until<br />

seen by a vascular surgeon, as<br />

wet gangrene can occur.<br />

2. When diagnosis is in doubt.<br />

For example, pyoderma<br />

gangrenosum is characterised<br />

by rapid ulceration and<br />

necrosis. Debridement is<br />

contraindicated as it may<br />

cause extension <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

ulceration (Chakrabarty and<br />

Philips, 2002).<br />

3. The <strong>debridement</strong> <strong>of</strong> malignant<br />

wounds serves no useful<br />

purpose and may cause<br />

bleeding. If diagnosis is in<br />

doubt, specialist help should<br />

be sought.<br />

4. When <strong>the</strong> patient is<br />

systemically severely unwell,<br />

for example, in ITU or terminally<br />

ill. Local intervention is unlikely<br />

to help heal <strong>the</strong> wound and<br />

patient comfort ra<strong>the</strong>r than<br />

<strong>debridement</strong> should be<br />

a priority.<br />

Conclusions<br />

There are four questions that<br />

should be asked before making<br />

a decision on how to manage a<br />

sloughy/necrotic wound:<br />

1. Is <strong>the</strong> tissue in <strong>the</strong> wound<br />

definitely slough?<br />

2. Is <strong>debridement</strong> appropriate?<br />

3. What is causing <strong>the</strong> slough<br />

within <strong>the</strong> wound? Infection?<br />

Poor blood supply?<br />

4. Are <strong>the</strong> causes being<br />

addressed?<br />

5. In choosing dressings which<br />

promote <strong>debridement</strong>, has<br />

moisture balance and patient<br />

preference been considered?<br />

If in doubt specialist help must be<br />

sought. WE<br />

Bellingeri A, H<strong>of</strong>man D (2006)<br />

Debridement <strong>of</strong> pressure <strong>ulcers</strong>. In:<br />

Science and Practice <strong>of</strong> Pressure<br />

Ulcer Management. Springer–Verlag,<br />

London:129–39<br />

Chakrabarty A, Philips TJ (2002)<br />

Diagnostic Dilemmas:Pyoderma<br />

gangrenosum. <strong>Wounds</strong> 14(8): 302–5<br />

Glossary<br />

Technical Guide<br />

Autolysis: natural degradation <strong>of</strong> dead<br />

tissue in a wound.<br />

Calcification: calcium deposits which<br />

may occur in a <strong>leg</strong> ulcer.<br />

Debridement: removal <strong>of</strong> dead tissue<br />

from a wound.<br />

Necrotic tissue/necrosis: dead tissue<br />

which is desiccated usually dark<br />

brown or black.<br />

Slough: yellow or grey or brown<br />

in coulour, wet stringy tissue that<br />

adheres to <strong>the</strong> wound bed.<br />

Eschar: dry necrotic tissue.<br />

INR: <strong>the</strong> time taken for blood to clot<br />

compared to a control. Normal range<br />

is 0.9–1.2.<br />

Gray D, White R, Cooper P,<br />

Kingsley A (2005) Applied Wound<br />

Management. In: Wound Healing: A<br />

Systematic Approach to Advanced<br />

Wound Healing and Management.<br />

<strong>Wounds</strong> UK, Aberdeen: 59–96<br />

Horrocks A (2006) Prontosan wound<br />

irrigation and gel: management <strong>of</strong><br />

chronic wounds. Br J Nurs 15(22):<br />

1222–8<br />

Leaper D (2002) Sharp Techniques<br />

for Wound Debridement. World Wide<br />

<strong>Wounds</strong>, Dec 2002<br />

M<strong>of</strong>fatt C, Morison MJ, Pina E (2004)<br />

Wound bed preparation for <strong>venous</strong><br />

<strong>leg</strong> <strong>ulcers</strong>. In: European Wound<br />

Management Association (EWMA)<br />

Position Document: Wound Bed<br />

Preparation in Practice. MEP Ltd,<br />

London: 12–15<br />

Thomas S, Jones M, Andrews AM<br />

(1998) The use <strong>of</strong> larval <strong>the</strong>rapy in<br />

wound management. J Wound Care<br />

7(10): 521–4<br />

O’Brien M (2003) Exploring methods<br />

<strong>of</strong> wound <strong>debridement</strong>. In: White<br />

R, ed. Trends in Wound Care. Vol<br />

2. Quay books, MA Healthcare,<br />

London: 95–107<br />

Wound Essentials • Volume 2 • 2007 73