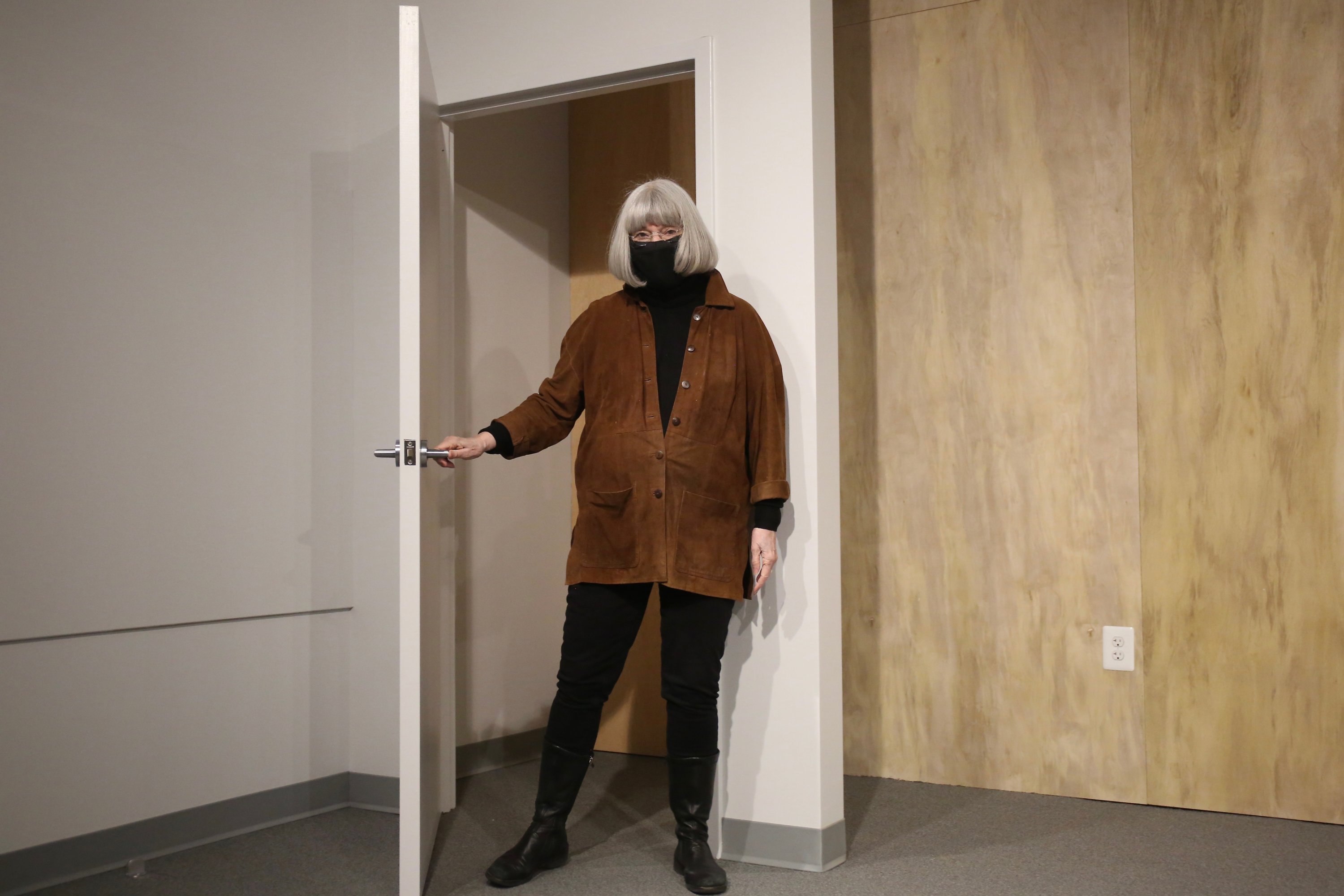

When Studio Acting Conservatory reopens to in-person instruction, students in the DC institution’s “Studio B” will be surrounded on two sides by reclaimed local history. The easternmost classroom’s “wing wall,” with doors on either side for perfecting entrances and exits, is covered in the old gray velour curtains from Studio Theatre’s old conservatory at 14th and P streets, Northwest, which Studio shut down in early 2019.

“We took them with us,” explains Joy Zinoman, who founded Studio and ran its conservatory after she retired in 2010, of the curtains. Her new conservatory operates independently of the theater.

And, more noticeable, perpendicular to that wall is a massive frieze of the Last Supper, which the school discovered when it began to rehabilitate its new space in Columbia Heights last year.

The conservatory’s building on Holmead Place, Northwest, was once the home of New Home Baptist Church, which commissioned local artist Akili Ron Anderson in the early 1980s to build an impressive altarpiece. Anderson built the bas relief using concrete and a coarse type of plaster called Structo-Lite and modeled Jesus and the disciples on people he saw around Columbia Heights, where he grew up. “It was very important to us that we have a black artist,” New Home trustee board chairman Willie L. Morris told the Washington Post in 1993. “All the other Last Supper pictures we’d seen were always in a white framework.”

Anderson told the paper about his work at New Home and other churches, “I think it’s important for black children sitting in churches all over this country on Sunday morning to look up at the windows, look up at images and see themselves and believe that they can ascend to heaven, too.” He’s now a professor at Howard University and you can see his artwork in many prominent spots across the Washington region, including his work Sankofa at the east and west entrances of the Columbia Heights Metro Station as well as stained glass at Howard’s Andrew Rankin Memorial Chapel and the Prince George’s County Courthouse.

When New Home moved to Landover in the 1990s, it found it couldn’t take the artwork with it—there’s probably no way to remove it without also removing the building’s exterior wall, Anderson told Washingtonian last year.

After New Home left, the building became a home to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Then, developers planned to turn it into condos. At some point over the following decades, the frieze was covered with drywall. Its background, once blue, had turned dingy and mostly gray. Zinoman’s school was surprised to find the artwork when it performed a gut renovation of the building. She tried to find a new home for the relief, but the same issues that kept New Home from moving it stymied others who were interested in giving the sculpture a new home, including a large church in New York.

Enter the National Museum of African American History & Culture. The Smithsonian Institution museum couldn’t take the sculpture, either, Zinoman says, but it was able to help conserve it. The museum confirms that a team led by Teddy R. Reeves, the museum’s assistant curator of religion, restored the mural. They began working on the mural in October, Zinoman says, cleaning it with small sponges and working around the lighting grid that hangs in the classroom, which they assured Zinoman was not a problem.

The conservatory finished the rest of its building with a cherry-red exterior and everything it needs for in-person instruction inside—just as the pandemic made teaching in person impossible. Shelves with props and furniture line the hallways. Downstairs there are two more studios, some offices, and a teachers lounge. Ensemble photos by Iwan Bagus decorate the walls, and a photo of the sculpture by Washingtonian‘s Evy Mages greets visitors in the lobby.

The school currently conducts classes virtually. When the new term begins in February, Zinoman says she and the rest of the school can’t wait “to be training actors in this wonderful red home.” Now, she says of the work: “We will be the steward of it—period.” A curtain on rails can cover the relief as instruction requires.

“Who would have thought in some dead old church in Columbia Heights,” Zinoman says, “you were going to have this miracle treasure?”