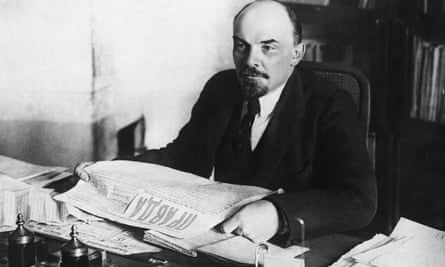

Sunday’s centenary of the death of Vladimir Lenin, one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century, will largely go uncelebrated in his home country of Russia this weekend, where the revolutionary leader stands accused of laying a “timebomb” underneath Russia and Ukraine that has exploded in the past decade.

There will be no parades or stirring speeches in Red Square. The obvious reason is that one of Lenin’s most strident critics is Vladimir Putin, who appears far more enamoured with the empire that Lenin’s revolutionaries overthrew.

Often portrayed in official Soviet culture as a grandfatherly, nurturing figure who ushered in the revolution of 1917, Lenin’s legacy is being repainted in darker hues, despite some pleas for the issue to be put to rest, both rhetorically and corporeally.

“In my opinion, the 100th anniversary of Lenin’s death creates an opportunity to try to move away from the endless passionate and meaningless bickering around the dilemma: is he an angel from heaven or a monstrous antichrist, the embodiment of absolute world evil?” said Vladimir Lukin, a Russian senator who formerly served as a human rights commissioner. But, he added: “Whether it will be used is another question.”

Putin appears to be unable to do either. He cannot stop talking about Lenin, nor is he ready to bury his body, which is embalmed in his Red Square mausoleum (the cost of preserving the waxy corpse was £140,000 a year in 2016). A third of Russians believe that the body of Lenin should be laid to rest as quickly as possible, according to a new survey by the VTsIOM pollster, but the question is viewed as so inflammatory that Lenin remains on public display, perhaps for another century to come.

“I believe we should be very careful here, so as not to take any steps that would divide our society. We need to unite it,” Putin told pro-Kremlin activists in 2016 on whether to bury Lenin. Rumoured plans to remove his body in 2024 were abandoned.

Once the lodestar of international revolutionary movements, Lenin’s influence has waned in the century since his death as his role in creating conditions for the brutal Communist dictatorship that emerged from the 1917 Russian revolution became ever more stark.

“I’m still undecided about Lenin’s heritage and his inheritance in the sense of what it means today,” said Christopher Read, a professor of history at Warwick University, who has written a biography of Lenin as well as the new Lenin Lives?, a review of his life and ideas. On the one hand, he said, the Chinese and other ruling Communist parties still trace their heritage back to Leninism. “But the idea that there’s a Leninist toolkit that radicals could reach into is probably inapplicable these days,” he added.

His international appeal in the west was strongest directly after the revolution until the events of 1956, when the brutality of his successor, Joseph Stalin, was denounced by the then Soviet Communist party leader, Nikita Khrushchev.

“What attracted people to Leninism was basically his anti-imperialism – the Soviet Union for better or worse was the most solid starting point for any anti-imperialist movement at that time,” said Read. “That’s why so many intellectuals, certainly mistakenly, had the idea that somehow Stalin’s Russia in the 1930s was the great new civilisation.”

Lenin’s influence on modern politics may be most keenly felt in China, where his vision of the party-state led by an ideological vanguard has become a political reality. Xi Jinping, the head of the Chinese Communist party, studied Marxist theory and ideological education at Tsinghua University from the late 1990s when he was a senior official in Fujian province. When he assumed power in 2012, he soon gave a speech to party officials in which he called on them to “practise core socialist values”, including Marxism-Leninism.

Not so in Russia, where Lenin has been roundly denounced and recast as a villain by Putin. In speeches dating back to 2016, Putin has blamed Lenin for appeasing nationalists and drawing faultlines into the Soviet system, creating national republics that would later have the right to secede from the Soviet Union. “What was this if not a timebomb?” he asked.

Lenin’s recognition that Ukrainians and Russians should live in different states, as well as his insistence that the industrial Donbas region remain in the Ukrainian republic, helped to bring Ukraine back into the fold after declaring independence in 1918, noted Serhii Plokhy , a professor of history at Harvard University. “But the price he paid for doing so seems excessive to present-day Russian opinion makers.”

In Ukraine, the countless city squares and statues named for Lenin before 2014 were seen as a relic of Russian colonialism, and the country in 2015 launched a broad campaign of decommunisation, taking down thousands of monuments and renaming tens of thousands of streets and squares, and sometimes whole towns and villages.

The ubiquitous statues of Lenin were a particular target - more than 1,300 were removed by 2016. When crowds in the city of Kharkiv managed to pull down a statue of Lenin, the tallest in the world at 8.5 metres, the regional government was forced to backdate an order for its removal after believing the crowds could not topple the statue. They were proven wrong.

Putin, announcing the most important decision of his presidency, the launch of the full-scale war in Ukraine, mentioned Lenin 11 times, as he angrily accused him of appeasing nationalists and of creating “Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine”, which includes lands Russia has now occupied in the east and south.

“You want decommunisation?” Putin said angrily in a speech just days before he launched the invasion. “Very well, this suits us just fine. But why stop halfway? We are ready to show what real decommunisation would mean for Ukraine.”

Yet even for some among the pro-Kremlin conservatives fighting in Ukraine, there is a nostalgia for Lenin as a powerful historical figure.

“The centenary of Lenin’s passing is being hushed up because he remains extremely pertinent, because Lenin is here, Lenin is alive, Lenin is at the forefront of a new world reconstruction,” wrote Zakhar Prilepin, a pro-Kremlin writer and paramilitary leader. “Every thinking Russian is proud that we had Lenin, that we have Lenin.”