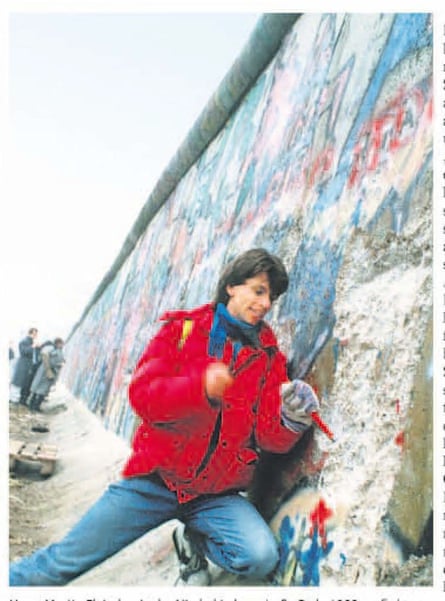

“The Berlin Wall was lifted – it did not fall,” insists Hans Martin Fleischer. The bureaucrat produces photographs and film footage shot on hand-held camera on 12 November 1989 – three days after the East German border was first breached. They show the first segments of the concrete barrier that had encircled West Berlin for 28 years being removed at night, amid a sea of camera flashes and applause.

Sparks fly as a worker in a hard hat uses an angle grinder to slice a huge slab emblazoned with a red swastika from one bearing an interlocking hammer and sickle – graffiti painted on the western side in protest at the 1939 non-aggression pact between the Stalinist and Nazi regimes, which paved the way for the second world war and the consequent division of Europe that led to the construction of the Berlin Wall.

Like a wobbly tooth, the slab finally gives way after being pushed back and forth by ripper teeth, before it is hoisted by crane like a trophy above the incredulous, cheering crowds on Potsdamer Platz.

“The communist authorities of East Germany (who remained in power until March 1990) choreographed that, I’m sure,” says Fleischer, a hobby historian who has forensically studied the events of November 1989.

Making the first inner city hole in the Berlin Wall was the surest sign yet that the authorities, contrary to widespread fears at the time, were serious about pulling it down. It was clear that footage of the action would go around the globe. That, coupled with the East German regime’s repeated attempts over the years to characterise the barrier as an “anti-fascist protection rampart” – “in their minds what better symbol could they have chosen to dismantle first than the swastika?” Fleischer says.

Thirty years on, he pulls open the creaking door of a warehouse in a wooded location halfway between Berlin and the Baltic coast that he would like to remain secret. Using a boat hook, he removes a large blue tarpaulin to reveal the swastika slab of wall, 3.6 metres high and weighing 2.7 tonnes, along with three other pieces that once stood alongside it on Potsdamer Platz. Pitted with holes from the pickaxe heads of border guards who chipped away at them before they were moved into storage, they are gathering cobwebs, rather than, as might have been expected, in a museum.

Fleischer, then a student of business administration, was driven both by historical fascination and an entrepreneurial spirit to buy up the wall segments on an impulse in 1990.

“I went to Japan shortly after the wall came down, and took small segments with me which got snapped up by everyone I met,” he says. “I was encouraged there by business people to find some intact pieces that I should buy and ship to Japan and I liked the business potential.”

He approached Limex, the company set up by the East German state secret police, the Stasi, to sell off the 155km stretch of concrete along with the watchtowers and other ramifications, who at first seemed surprised at the interest but soon realised the opportunity to make money.

“They gave me a plastic folder containing page after page of photographs of the sections. They were randomly numbered, but I managed to find the four pieces that had been adjacent to each other. They wanted 385,000 deutschmarks for them,” Fleischer recalls. The parties eventually agreed on a five-figure number, though he does not want to reveal exactly how much. “I borrowed some money from among others, my dad, a history teacher, who appreciated their symbolic value above all”.

The deal with the Japanese fell through. A sale to a Monacan auction house subsequently collapsed, he believes because it coincided with a neo-Nazi attack on a Jewish cemetery. Countless museums and Wall-lovers also turned him down. “The swastika made it impossible to sell,” he says. “I think if Mickey Mouse had been on them, it would have been a different story: less complicated, less divisive.”

Interest in the wall soon began to wane, with the war in Yugoslavia casting a shadow over the euphoric mood that had gripped Europe following the toppling of communist governments from Poland to Romania. He put the segments in storage.

“I thought it would be wise to wait until the 10th anniversary and allow a certain historification process to take place before trying my luck again,” Fleischer says. He resisted the urge, as at least one highly successful businessman has done, to break his artefacts into hundreds of thousands of fragments, which continue to be sold in Berlin souvenir shops and on the internet, sometimes accompanied with a certificate of authentication, for up to 50 euros apiece. “I was clear from the start these sturdy witnesses of history, marking the first cut in the Berlin Wall, had to stay intact and together,” he says.

Having long since shelved his ambitions to sell his remnants, Fleischer’s historical interest has only grown. He made a life-sized, surprisingly realistic copy of the now-lost hammer and sickle section out of styrofoam and has transported it on the roof rack of his car to over 20 countries. His accompanying photographic project has captured it next to the Eiffel Tower, drawing smiles in war-torn parts of Ukraine and on a plinth alongside Copenhagen’s Little Mermaid. His message, the self-proclaimed “maueraktivist”, or wall activist, says, in reference to the peaceful people’s revolution of 1989, is: “Human actions can change everything.”

He has plans to float it in the Mediterranean in protest at refugee drownings and to take it to Northern Ireland, amid Brexit ambitions to reinstate the border there.

He has also still not given up on his attempts to re-erect the authentic wall segments somewhere, ideally on or as close as possible to their original location. He produces the precise coordinates as to where it once stood. Hogging the site now is a nondescript gleaming glass and concrete commercial block, typical of the new-builds to have sprung up along the former Wall route in the past three decades. The owner, a Spanish property developer with headquarters registered in Luxembourg, has not responded to his request for a meeting to discuss, as he put it to them, the possibility of “putting the segments, important symbols of European division, on public display”, or at the very least referring to their former presence there.

Fleischer recalls abandoning the party he was at when TV news reports started coming through that the first openings had appeared in East Germany’s borders. The then-24-year-old perched himself high on the column of the Böse Bridge in northern Berlin, and watched for hours the stream of Trabant cars roll over the bridge into the west.

“I thought how lucky I had been as a West German to have been on the ‘right’ side of the border, whilst all those people across the communist east had suffered, in effect been punished for the crimes of Nazi Germany, through decades of division and entrapment. Now at last they were free.”