Why did East Timor hold a referendum in 1999?

The landmark vote in 1999, in which 78.5% of East Timorese chose independence from Indonesia, was the culmination of 24 years of occupation by Jakarta and, before that, hundreds of years of colonial rule by Portugal.

Why did Portugal relinquish its far-flung colony?

In April 1974 a leftwing coup in Lisbon, the Carnation Revolution, led to Portugal setting its colonial outposts adrift. It withdrew its administrative and military personnel – including from Mozambique, Angola and what was then called Portuguese Timor.

What happened once they left?

Local elections were held in East Timor and the two biggest parties – the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin) and the Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) – formed a coalition, but it did not last long. Fighting broke out, there was an attempted coup by UDT, and then Fretilin unilaterally declared independence on 28 November 1975.

What was Indonesia’s reaction?

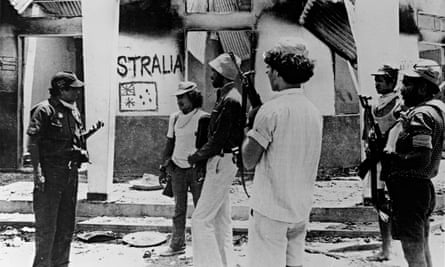

Indonesian forces had already secretly begun attacks across the border from Indonesian West Timor (on the other side of the island) in October 1975, where five Australian journalists were killed in the town of Balibo. Jakarta feared a communist state on its doorstep and that a newly independent country in its sphere could destabilise the rest of the archipelago. It launched a full-scale invasion of Timor in December 1975.

Why were the East Timorese so opposed to Indonesian rule?

Portugal’s colonial influence meant the population was culturally very different from the rest of Indonesia. The vast majority of East Timorese are devout Catholics and speak their own language (Tetun).

What happened after the invasion?

The Indonesian forces were brutal. As many as 200,000 people are thought to have perished in fighting, massacres and forced starvation. Fretilin and its armed wing, Falintil, retreated to the interior of the island with tens of thousands of civilians. It’s thought 100,000 died in the first few years, as the armed resistance was largely crushed and Indonesia held civilians in detention camps where many died in a famine. In July 1976 Indonesia’s parliament declared East Timor the country’s 27th province.

How did the world react?

Many countries, including Australia, effectively looked the other way, prepared to appease Indonesia because of its size and power in the region. In 1978 Australia’s prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, was the first to recognise Jakarta’s de facto annexation. But the UN condemned it and called for an act of self-determination.

What happened to the Timorese resistance?

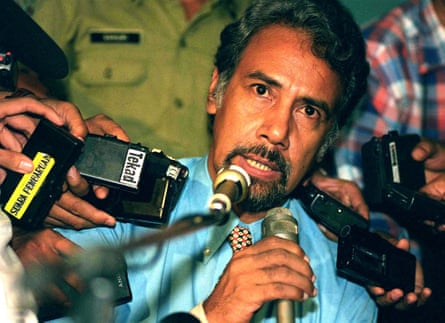

In 1992 the head of the resistance, Xanana Gusmão, was captured and imprisoned in Jakarta. It was an almighty blow. The year before, leaked footage of the massacre of 100 mourners at a funeral at Santa Cruz cemetery in Dili had emerged, reminding the world of the brutality of the occupation. In 1996 the country’s de facto foreign affairs minister, José Ramos-Horta, was jointly awarded the Nobel Peace prize with Bishop Carlos Belo, the head of the Catholic church in Timor.

Why did Indonesia change its stance towards East Timor?

In 1998 a political earthquake brought change to Indonesia. The Asian financial crisis and massive pro-democracy protests led to the resignation of the country’s strongman, President Suharto, who had been in power for more than 30 years and had authorised the invasion of Timor. Suharto’s successor, President BJ Habibe, was more open to some form of autonomy for East Timor, and released Gusmão from prison in Jakarta, into house arrest. In March 1999 Habibe announced that if, in a “process of consultation”, the East Timorese favoured independence over autonomy under Indonesia, he would grant it.

What happened in the referendum and its aftermath?

On 30 August 1999 the UN oversaw an historic ballot, in which 78.5% of East Timorese rejected autonomy in favour of independence. Celebrations across the country were short-lived. Indonesian-backed militia groups who had terrorised the population before the vote stepped up their attacks, aided by Indonesian security forces. A three-week campaign of violence killed 2,600 people, nearly 30,000 were displaced and as many as 250,000 were forcibly shipped over the border to Indonesian West Timor after the ballot, in what amounted to a scorched earth policy.

How did the world respond?

On 20 September 1999 an Australian-led international peacekeeping force, Interfet, arrived to restore order. But extensive damage had been done. Towns and villages were decimated and vital infrastructure was ruined. Gusmão and other exiled leaders returned soon afterwards and the UN ran a three-year administration in the lead-up to parliamentary and presidential elections. In May 2002 Gusmão was inducted as president of the newly named Timor-Leste.