Jimi Hendrix did not need a match to burn the American flag. All he needed to desecrate Old Glory was an electric guitar. When Hendrix started to play the national anthem at Woodstock in 1969, the audience must have been baffled. Patriotic bullshit, man! But as he played The Star-Spangled Banner, he distorted it to produce increasingly painful, harsh and violent sounds. The Vietnam war and the dissonance of a US at odds with itself throb in the surreal chaos Hendrix makes of a song written in 1813 to express love of the flag:

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Recently, it had not been so much waving as smoking. For what Hendrix did at Woodstock was translate the fiery anti-war protests of the 1960s from image into sound. In 1967 in Central Park, the star-spangled banner was burned in a much more literal way when the flag was set alight at a huge anti-war protest caught on camera in pictures that define the era. The squares were shocked, as they were meant to be, by a photograph of a ragged countercultural mob hailing the flaming flag, waved aloft in a parody of patriotic display. In another picture from the same protest, the bright flames of the blazing Old Glory light up a misty day as if bringing the napalm brutality of war from Vietnam’s burning villages into the heart of the US.

Nearly 60 years on, Donald Trump has sought to rekindle passions over the right of every freeborn American to burn the flag. In one of his trademark early morning tweets, at 3.55am on Tuesday, he declared: “Nobody should be allowed to burn the American flag – if they do, there must be consequences – perhaps loss of citizenship or year in jail!”

It was immediately pointed out that the US Supreme Court has in fact upheld flag-burning as a form of free speech protected by the first amendment, in verdicts delivered in 1989 and 1990 and defended even by Trump’s favourite Supreme Court justice, Antonin Scalia – and that stripping Americans of their citizenship would be a novel penalty to say the least. Why not the death penalty for cable theft while he’s about it? Yet once again, Trump’s critics are taking him too “literally”, reading his tweet as an outline of policy when surely it is an emotive match thrown into one of the US’s most divisive cultural conflicts by a political arsonist of proven ability.

It works as a provocation because flag-burning has a warm and special place in US cultural history. It does not serve as quite the same flash point elsewhere, and anyway, when non-Americans gather to burn a flag, it is often the American one they burn. There’s just something very flammable about that flag.

Of course, it’s easier to burn the stars and stripes wherever you happen to be because if you burn your own national flag in a wide range of countries, including Algeria, France, Portugal and Switzerland, you can face a hefty prison sentence or substantial fine. Denmark, on the other hand, allows the burning of its own flag but bans attacks on foreign flags for fear of starting a war.

Those countries are not cursed, as the US’s less liberal lawmakers are, by a constitution that has enshrined freedom of speech since 1791. Burning the flag has become a powerful symbol of that free speech – and the history of this iconoclastic act should warn Trump that he won’t get a free ride to trample rights. The fact that many Americans hold it to be a truth self-evident that flags were made to burn reveals how strongly resistance to power is written into the US’s history.

That resistance can come from right or left. The first recorded American flag-burners were angry southerners protesting against Abraham Lincoln on the eve of the civil war by destroying the banner of the Union. The Confederacy’s rejection of the Union meant repudiating its flag – and the new flag they invented for themselves is the original punk American outrage against Old Glory. The Confederate flag of a different, racist America still has a nasty shock value today. Yet after the northern states triumphed in the civil war, the stars and stripes became sacred in a new way. The flag of the union was revered as an incorruptible national image. In a republic that had no monarch, no thrones or traditional regalia, the flag became the beloved, abstract “face” of the US. The British national anthem asks God to save our ruling monarch. The US’s pours sentiment on the flag.

That was why, by 1897, a national organisation was founded to protect the US flag and many states passed acts to ban its desecration. Not that many people did burn the flag in 19th-century America, except when the occasional flag-waving politician provoked opponents to set light to the banners waved by their supporters. Flag-burnings were extremely rare in the 20th century too – until the 60s.

The sudden urge to burn flags that gripped the young in the 60s was not just about Vietnam. It has to be understood as part of a new attitude to images that started with pop art. Fascinatingly, the reason flag-protection laws appeared in the US in the first place was to prevent the use of the stars and stripes by advertisers and product designers. It was commercialisation that threatened to trivialise the sacred banner.

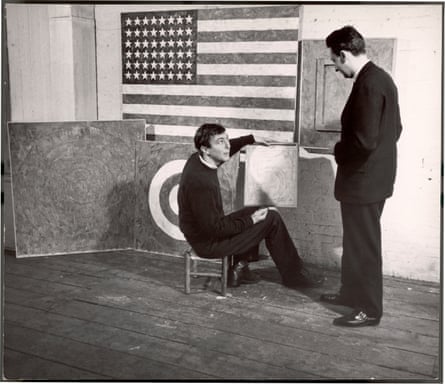

In 1907, two businessmen were convicted of misusing the flag by putting its image on bottles of Stars and Stripes beer. Fifty years later, that case belonged to a forgotten, innocent past. The flag was just part of the rush of reproduced images that shapes modern life. Pop artists saw it as an icon to appropriate, like Coke or Campbell’s soup. In Jasper Johns’ 1954-5 masterpiece Flag, the stars and stripes becomes both a painting and a sculpture, overlaid on collaged newspapers. Is this flag abuse? If so, it was just the beginning of a wave of subversion that would see Bob Dylan unfurl a giant stars and stripes as he played Like a Rolling Stone, Robert Frank ironically photograph flag-waving middle Americans and, in gestures that had the ritual quality of performance art or a blasphemous sabbath, people burning the flag more and more from 1965 onwards to protest against violence and war.

Lyndon B Johnson responded with a federal law against flag desecration in 1968, and that in turn inspired yet more burnings and art. At the Judson Memorial church in Greenwich village, hundreds of artists gave work to The People’s Flag Show in 1970 for an exhibition that brought together pop art and politics.

The Supreme Court finally recognised in 1989 that flag-burning is not just mayhem but a meaningful cultural act: a way of saying something. It is, in the court’s words, a form of “symbolic speech”. This recognition of a violent gesture not as mere vandalism but a type of “speech” is an amazing insight into the culture of protest. When words fail us, we use images. When a nation creates a sacred image of itself – the eternal American icon that is the star-spangled banner – it also provides an instant, potent means of symbolic dissent. As the artist Dread Scott asked in 1989 in an installation that upset George Bush Sr: What is the Proper Way to Display a Flag? To answer the questionnaire, visitors had to stand on a flag laid on the floor. Trampling the flag is another way to hurt it.

Americans who believe in free speech don’t need to go far to protest against Trump’s latest disrespect of their venerable constitution. Just burn the nearest flag. It’s the American way to dissent.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion