Phil Daniels’s “Man of the Year” appreciation of Patrick Marber in Arena magazine started with the line “Patrick Marber is a c***”. The playwright concedes that in the course of directing his 1995 debut, Dealer’s Choice, he and Daniels crossed swords. “But we’re great mates. He did nominate me as Man of the Year.” David Quantick, a writer who worked with him back in the days when he was toiling on Channel 4’s late, unlamented Saturday Zoo, hints that Marber “doesn’t have people skills. He’s not good at small talk.”

Marber demonstrates this when I ask if he’s moving to New York when Closer, the award-winning follow up to Dealer’s Choice, transfers there next year. “Well, I am directing it so I think it would be a good idea if I was in the general vicinity, don’t you?” It was a stupid question, but Marber has a manner that makes all questions seem stupid.

Certain performers from his days writing television comedy grumble about feeling patronised and alienated. One source recalls a meeting where, in front of eight other writers, Marber reprimanded Steve Coogan for not understanding Alan Partridge, Coogan’s own character. “No, Alan wouldn’t say that,” Marber hissed sternly.

Talking to him, one does feel somewhat alienated, primarily because he is smarter than most people. Patrick Marber, like your mother, generally does know better. If he says “Alan Partridge wouldn’t say that”, or “Scooby Doo wouldn’t say that”, he’s probably right. His perceived arrogance stems from the fact that he is utterly focused on everything he does, so much so that there is simply no time for “people skills”.

Victoria Coren remembers, years ago, being fascinated by him purely on the basis of how he played poker. “He always reminded me of the opening line of The Cincinnati Kid: ‘He was a tight man. Everything about him was close and quiet, his gestures were short and cleared with no wasted movement.’” The truth is that he is paralytically shy. Performer and writer Beth Porter, who has known him since he was 16, recalls: “It used to be so bad, he couldn’t take his eyes off the floor, let alone look you in the eye.” Marber grew up in a middle class Jewish home in Wimbledon. “I consider myself a Jewish writer, like all my heroes: Tom Stoppard, David Mamet, Philip Roth, Arthur Miller, Woody Allen.” At Oxford he met Guy Browning and formed a comedy double act before going it alone. Part of his shtick was ultra-concise impressions, Dustin Hoffman and Kenneth Williams in a syllable.

When he was doing standup, was he thinking: I really want to be a playwright? “No, I was thinking ‘I really don’t want to be a stand up.’” So it’s true that standup comedy is the most frightening thing in the world? “Well its not as frightening as being blown up in a war. But no, I didn’t like it and when I see standups now, I can’t believe I ever had the guts to do it. Eventually, I gave up on it at the same time as the love of my life gave up on me. I went to Paris for six months and wrote novels that no one will ever see.”

At Marber’s lowest ebb, Armando Iannucci, whom he had known at Oxford, asked him to do Radio 4’s On the Hour. “If he hadn’t cast me I would have probably taught English as a foreign language and had a miserable life. Instead we all got this simultaneous break: me, Armando, Steve, Rebecca Front, Doon MacKichan. It was a really good time, the early nineties.” This is the first time Marber has cracked anything resembling a joke. He has an almost childlike seriousness, and with his neon pale skin and intense eyes, resembles no one so much as Bud Cort in Harold and Maude.

Scoffers say that Marber was “no actor”, but many of the best Iannucci/ Coogan characters were his: the Gary Oldman style actor who claims to have punched Jessica Tandy but ends up fixing a photocopier is a personal favourite.

“Gradually,” says Beth Porter, “his natural facility to see the absurd and funny things in life became enriched by his understanding of pain. That development is what made Dealer’s Choice such a remarkable first effort.” “It’s all a stab in the dark really,” mumbles Marber. “Just because I’ve written a play about sex that people quite like, doesn’t make me Doctor Ruth.” On Friday, Closer, this play about sex that doesn’t make him Doctor Ruth, was named best comedy of the year at the Evening Standard Drama awards. It is a strange category for the striking, vicious play to be even considered for. “I know,” giggles Liza Walker, one of its two female stars. “Yep, seems really funny now,” she deadpans.

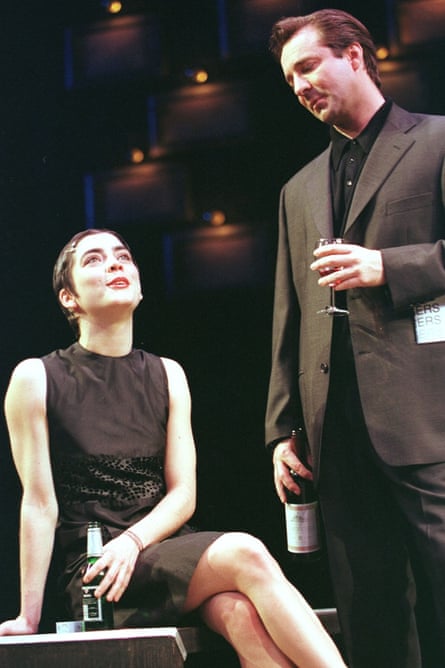

Walker plays Alice Ayres, a waifish stripper who has been plucked from a road accident by obituarist Dan (Mark Strong) and tended by Doctor Larry (Neil Dudgeon). The fourth corner is Sally Dexter’s Anna, a photographer who begins an affair with Dan when she takes the jacket photo for his debut novel. He is already living with Alice and Anna is married to Larry. It sounds like the basis for French farce, but the approach is very chilly, very English. Titled with the utmost irony, Closer should really be called Further Away. The play opened in May to ecstatic reviews anointing Marber the new Pinter, Stoppard and Tennessee Williams. Like Williams, he has written uncommonly perceptive and sympathetic roles for women, especially young women.

Before Closer, Walker, who gives arguably the most moving performance, had never even been on stage and was languishing in cheesy TV roles. “You know,” she says cheerfully, “drug addicts, teen prostitutes. The usual rubbish. And Patrick gave me this part on the first reading, and has continued to give me total support.” She has nothing but praise for him. “There’s a lot of stuff in that head and if you can get any of it out you’re laughing.” David Quantick hasn’t seen either Dealer’s Choice or Closer, yet he still thinks Marber is a genius. “Not many people who worked on Saturday Zoo ended up at the National. I suppose he’s a poshed up Ben Elton.” That may sound like a backhanded compliment but Quantick is a fan. There are, however, Marber detractors. Some say that, stylistically, Closer is no more than a cross between Men Behaving Badly and Last Tango in Paris. One old acquaintance feels that Dealer’s Choice “wasn’t even that funny. Even when it got dramatic, it was no different from a Mamet play.” So? “So Mamet’s done it already. I really am surprised at how well regarded that play is.’ He concludes his critique by chanting ‘Stitch him up! Stitch him up!’”

Is Marber aware that a lot of people don’t like him now that he’s the New Pinter? He audibly catches his breath: “Don’t they? Well, I don’t try to be likeable. The worst thing people do is present versions of themselves to the world that aren’t real. Enough people like me. Enough to let me sleep at night.” There’s a line towards the end when Larry yells at Dan “You writer!” and it’s an insult. Is it an insult? “I think writing is a glorious and noble thing. Anyway, it’s a direct nick from Beckett: ‘You critic!’” Do you think comedy writing is glorious and noble? “I suppose I must have done.” Sniff. “At the time.” Now, don’t you think that Coogan and Iannucci and everyone else on On the Hour and The Day Today might find that response a little insulting? Pause. “I found it very difficult doing collaborative writing. I’m not really a good team player.” But you were supposed to be involved in the current series of Alan Partridge? “I was around for early meetings. I helped evolve what it was going to be. I’m very keen that Alan should become darker. I argued very strongly that he shouldn’t have a chat show, that it should be set in the hotel. If I had had time, I would have been involved.” Do you miss it? “Not greatly.” Do you think this series merits its rapturous reviews? Pause. “I suppose it makes me laugh.” Again, Marber’s curious manner does little to dispel rumours that there has been something of a falling out. Beth Porter disagrees. “That’s just Patrick’s brand of understatement. He’s not given to great effusion. If he said ‘I suppose it makes me laugh’ it probably means that he loved it.”

He sounds suddenly nervous. “There hasn’t been a falling out. Not that I’m aware of. I know I can come across as rude. I’m just very shy. I’m especially bad at meeting people. It’s my curse. I don’t like the Groucho Club or Soho House, places where there are mad people who have done a lot of coke and are going to talk in my face. I exist in splendid isolation.” In fact he lives with his girlfriend and his beloved dog, Mrs Riley, although it is true, he only ventures out to go to the cinema or the casino. And in fairness, the understatement with which he appraises other people’s work is always applied to his own. “I’ve written two plays and been in a comedy show. I hope one day to be big deal. Write something that might survive.” He has already done that. Closer, comedy or not, articulates the politics of emotion with the same pitiless observation Marber had as a television writer. He conveys how love, in the final humiliation, destroys your sense of style. It makes you say and do things that you always had contempt and pity for when you witnessed them in other people. Closer, more than anything, is about neurotic connections and how people in search of peace never enjoy any kind of serenity as long as they are searching.

Marber’s reputation as patronising and alienating is unfair if explicable: people who are creative and know what they want to do get misinterpreted. Because most people aren’t creative and don’t know what they want, opting instead to spread themselves as thin as Marmite in the drinking clubs he so dislikes. It is the ones who aren’t good at small talk, the ones who sound like they hate their friends and their careers and their lives, who come out with such definitive works as Closer at such a young age.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion