After one last look at Saturn and its moons, Nasa’s Cassini spacecraft will call time on its 20-year mission on Friday when it dives headlong into the giant planet and burns up in the atmosphere.

And so a man-made meteor will streak across Saturn’s sky soon after 11.30 am UK time, though confirmation of the spacecraft’s demise more than a billion kilometres away, and on the wrong side of the asteroid belt, will not reach Earth for another 83 minutes, when the signals beamed home from the probe fall silent.

The moment will mark the end of an eight billion kilometre journey that began at Cape Canaveral in Florida in 1997 and took Cassini around Venus and Jupiter en route to its destination. There it circled Saturn nearly 300 times and made observations that transformed scientists’ understanding of the most distant planet visible to the unaided eye.

For its swansong, the spacecraft will gather data on Saturn’s clouds as it hurtles towards them at 112,000 km/h. At that speed, even in the wispy vapours 1,500km above Saturn’s cloud tops, Cassini’s thrusters will struggle to keep its antenna pointed towards Earth. When they can no longer hold the spacecraft steady, it will start to tumble, communication will be lost, and the probe will burn to a cinder.

At Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California, scientists and engineers, some of whom have been on the mission since its conception in the 1980s, will gather in the early hours of Friday morning to witness Cassini’s final moments before joining other missions, perhaps to Jupiter or Mars.

“It’s going to be tough to say goodbye, but I’m very proud of all Cassini has accomplished and to have been part of the mission from the very beginning, ” said Linda Spilker, project scientist at JPL, who began work on Cassini in the 1980s. “It’ll be a mixture of sadness and pride and joy at having worked on the mission and saying goodbye to my Cassini family.” Some offices have already emptied as staff found posts on Nasa’s Juno mission around Jupiter, the agency’s Mars 2020 rover or the Europa clipper, which aims to find out whether the Jovian moon is habitable.

Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004 and spent 13 years observing the planet with a suite of instruments. It is now known to have millions of rings, thought to be the remnants of a moon that strayed too close and was torn apart by Saturn’s immense gravitational field. Stunning pictures captured Saturn’s weather, a once-in-30-years storm that engulfed the globe, and the changing of its seasons. Over the mission, the northern hemisphere shifted from a bluish hue to the more familiar golden tones as the shadows cast by Saturn’s rings moved south.

But this was a rarity in space adventures: a mission to a planet where the moons were the stars. Carried onboard Cassini was a European lander, named Huygens, which set down on Titan, Saturn’s largest moon. It was the first ever touchdown on an alien world beyond the asteroid belt. On Titan, bright and feathery methane clouds float in the sky and dump rain on the surface, at times producing terrific floods. Hydrocarbon rivers carve canyons on the ground and feed three hydrocarbon seas and hundreds of lakes.

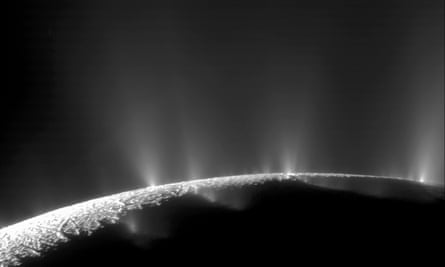

And then there is Enceladus, a Saturnian moon a mere 500km wide. From 23 flybys, Cassini made the extraordinary discovery that beneath its icy surface, Enceladus harbours a global ocean of liquid water bearing salts and simple organics that spray into space from its southern pole. Hydrothermal vents are thought to warm the hidden ocean’s floor. On Earth, such vents are havens for life.

It is Titan, Enceladus and other Saturnian moons, including Mimas, whose giant circular pit makes it look worryingly like Star Wars’s Death Star, that sealed Cassini’s fate. Fearful that the spacecraft might crash-land and contaminate one of the pristine moons, mission controllers set Cassini on a collision course with the planet itself. Saturn is an enormous ball of gas with no discernible surface, and when Cassini plunges in the probe will become a fireball. Any tiny fragments that survive the inferno will sink, melt, and ultimately become diluted in the planet’s interior.

Funded with £3bn ($3.9bn) from Nasa, the European Space Agency, and the Italian Space Agency, the mission honours Giovanni Cassini, the 17th century Italian astronomer who spotted four of Saturn’s moons, and Christiaan Huygens, his Dutch contemporary who discovered Titan and was first to propose that Saturn had rings. It has already produced 3,948 research papers, but scientists will ponder the data for years to come. In recent weeks, Cassini has beamed back information on Saturn’s enigmatic rings that could answer fundamental questions about their make-up. One question the probe may answer on its death plunge is how old the rings are. “I can’t wait to dive into the incredible ring data,” said Spilker. “What would it look like if I could hold a ring particle in my hand? Would it look like a fluffy snowball or an icy shard?” Cassini found fluffy lumps of material the size of mountains in two of Saturn’s rings. The huge outer “E” ring forms from the icy plumes that spray from the unexpectedly active Enceladus.

Spilker is part of a Nasa team that proposes to go back to Enceladus to look for signs of life. One idea is to fly through the salty plumes and capture material in case stray microbes are blasted out with it. “Cassini didn’t have the instruments to make the measurements, to see if there might be organisms coming out with that briny spray,” she said. “I’d love to answer that question in my lifetime. Does the ocean of Enceladus have evidence of life?”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion