The mosque

Crystalline stucco, glistening tiles, inlaid wood and walls decorated with ramifying patterns, which on closer inspection include words from the Qur'an, are among the wonders of Islamic religious art. The emergence, early in the history of Islam, of a scepticism about the value of images did not limit possibilities for decorating places of gathering and prayer. On the contrary, the interiors of mosques proliferate with unprecedented abstract invention almost from the very first Arab conquests in the early middle ages.

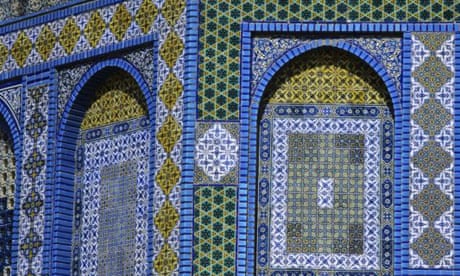

The oldest surviving Islamic religious buildings, such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (built by 691), are visibly influenced by the mosaics of Byzantium. But already in the Dome of the Rock there's more interest in repeated motifs from nature than in iconic faces and bodies. The mosque, with its expansive interior and even vaster courtyard, evolved from the house of the Prophet Muhammad in Madina; the unique decorative features that started to appear in mosques by the eighth century include the mihrab - a large niche set into the wall that faces Mecca, conventionally explained as a visual indication of the direction in which to pray - and the minbar, a raised platform and lectern comparable to the pulpit in European churches. These are often highly ornate and exquisitely beautiful, many placed in museums, in Islamic and non-Islamic lands, as works of art in their own right.

One of the most powerful examples of medieval Islamic art in a museum is an entire wooden minbar from Egypt, its tall, towered frame carved into geometrical interlapping star-shapes inset with white ivory. This mathematical pattern, its order relieved by opulent ivory details and organic truth - like a microscopic view of snowflakes or minerals - is a captivating example of the patterning that, with their spiritually inspired studies of mathematics and knowledge of ancient Greek science, medieval Muslims perfected.

An earlier and even more spectacular example of Islamic religious art's subtle combination of rich texture and complex symmetrical order is the mihrab in the Great Mosque at Cordoba, created in the 10th century for al-Hakam II. Interweaving stucco patterns are juxtaposed, as in an illuminated manuscript, with words from the Qur'an: this use of the written word to decorate a building is one of the crucial characteristics of Islamic art. Luxurious manuscripts of the Qur'an such as the ninth-century Blue Qur'an with its gold letters on blue parchment are very different from Christian illuminated manuscripts with their images and marginalia: the words of Islam's holy book are presented as purely as possible and themselves become the "art". Mosque and book, word and decoration flow into one another in these masterpieces of Islam.

Key works

Mosaics in the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem (691)

Mosaics in the Great Mosque, Damascus (706)

Blue Qur'an, gold on blue parchment in Musée des Arts Islamiques, Qayrawan (9th century)

Richly decorated mihrab of the Great Mosque at Cordoba, Spain (10th century)

Minbar in bone and wood from the Kutubiyya Mosque, in Badi' Palace, Marrakesh (begun 1137)

Mihrab from Mosul, in Baghdad Museum (13th century)

Mihrab from Isfahan, Iran, in Metropolitan Museum, New York (c1354)

Wood and ivory minbar from Egypt, in V&A (c1470)

Interior of Mosque of Shaykh Lutfallah (1603-1619)

The palace

The court art created for Islamic rulers in the middle ages soars on a magic carpet ride of imagination and grace. Light, airy palaces were decorated with shining tiles, honeycomb-like stucco vaults and hypnotically patterned carpets. The pleasures of life were celebrated in intricate perfume bottles, lustrous serving dishes and magnificent water vessels. Monstrous beasts such as a green copper-alloy griffin with curvaceous wings and throat and sharp beak and ears, today in the cathedral museum in Pisa, Italy, bring to mind the fabulous world of the 1,001 Nights.

Islamic court art reached its heights in al-Andalus, the Muslim kingdom in Spain established by 740 and destroyed by the Christians in 1492. The rulers of al-Andalus proclaimed their faith with Cordoba's Great Mosque and Seville's Giralda minaret, but it is the ethereal luxury of Andalusian court art that has captivated later generations. The art of using plaster to decorate buildings is taken to truly fantastic lengths in Andalusian masterpieces such as a stucco doorway from the Aljaferia palace in Saragossa, today in Madrid's Archaeological Museum.

Out of two strait-laced columns at the bottom of the doorway spurts a phoenix flame of pulsing ornament. The design mocks architectural common sense - it includes representations of a broken or falling buttress - and the fiery splendour of the "arabesque" joyously contradicts the neat, even design on the upper doorframe. This is not architecture but pure, purposeless art.

It's even more beguiling to see such effects, with immense structures of cascading plaster dangling above geometrical patterns repeated across vast walls of lustrous tiles, in the unique Alhambra in Granada - a dreamer's palace that floats above the city. Far from being hostile to all figurative depiction, Islamic medieval art abounds in images of animals, including the stone lions in the Alhambra's Patio de los Leones, yet it's the enigmatic, spiritual beauty of geologically cavernous stucco vaults and cool blue tiles that is so unreal.

Lustreware - the use of metal to create dazzling pottery glazes - was invented by Islamic artists and ancient ceramics still glint in their museum cases. Even after the reconquista, Andalusian artists continued to create fabulous interior spaces for Christian palaces, while the Muslim arts of luxury reached new heights in 16th-century Istanbul at the court of the Ottomans.

This was the age when European artists such as Holbein started depicting the intricate weaves of eastern carpets. One the greatest of all surviving Islamic carpets is the hypnotically decorated Ardabil carpet, woven in 16th-century Iran under the Ottomans' rivals the Safavid dynasty, that can be seen today in London's V&A.

Key works

Marble window grille from Al-Andalus, now in Cordoba Provincial Archaeological Museum, Spain (11th century)

Stucco doorway from the Aljaferia, Saragossa, now in Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid (11th century)

Patio de Los Leones, Alhambra, Granada (11th century)

Gilded silver perfume flask with niello inlay, in Museo Provincial de Teruel, Spain (c1044-1103)

Pisa Griffin, copper-alloy figure of a griffin, in Museo dell' Opera del Duomo, Pisa (11th century)

Stucco decorated interiors of the Alhambra (begun 1052)

Blue underglaze painted and incised ewer from Iran, now in Metropolitan Museum, New York (1215-1216)

Copper-alloy basin inlaid with silver, in Freer Gallery of Art, Washington (1239-1249)

Underglaze painted bowl from Syria, now in Metropolitan Museum, New York (13th century)

Ardabil carpet from Tabriz, Iran, now in V&A (1539-1540)

Court painting

A young prince stands robed in orange in a green garden. The pearls, rubies and other precious stones hung around his neck, dangling from his ear as he presents his moustached profile to us, wrapped around his head-dress and held contemplatively between slender fingers as he admires a fine jewelled object play against the flower petals that dance on the dark grass. The subject of this exquisite painting on paper, Shah Jahan, inscribed it in his own hand: "A fine likeness of me in my 25th year, by Nadir al-Zaman."

This portrait of a Mughal prince was created in India in the 17th century - but the tradition it embodies comes from another time and place. The Muslims who established the Mughal empire in 16th-century India were inheritors of painting styles developed at Islamic courts in Iraq and Iran in the middle ages. In 1258 the Mongol rulers of China conquered Baghdad; they established the Ilkhanid dynasty in Persia and in their wake Islamic book illumination became more painterly and ambitious. The Mongols brought with them the influence of Chinese painting, while paper became readily available for artists to experiment - giving entire pages over to sophisticated, lush pictures illustrating histories and secular stories.

The pictures signed by Junayd in a manuscript collection of poems copied in Baghdad in 1396 create a dreamlike world of enchanted palaces whose painted window grilles and carpets are reminiscent of surviving medieval Islamic palaces; the romantic cityscape of Junayd's scene of Humany on the Day After his Wedding becomes, in the later art of Mughal India, a paradise of gardens, jewels and elegant princes. These are lovely visions of pleasure.

Key works

Humay on the Day After his Wedding Has Gold Coins Poured Over Him as he Leaves Humayun's Room, painting by Junayd (1396)

The Seduction of Yusuf, painting by Bihzad (1488)

The Youthful Akbar Presenting a Picture to his Father Humayun, painting from Mughal-period India, now in the Gulistan Palace Library, Tehran (late 1550s)

Akbar Hunting, outline and portraits by Miskina, painting by Sarwan (c1590)

Babur Supervising the Laying Out of the Garden of Fidelity, painted by Bishndas; portraits by Nanha (c1590)