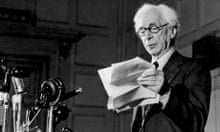

Bertrand Russell was an intellectual giant of the 20th century who bore witness to his generation's painful transition from Victorian optimism to postwar trauma. He always believed that ideas could change the world. He was closely involved in many of the events that shaped world politics during the first two-thirds of the 20th century. Controversially, he opposed the first world war, and was a prominent peace activist.

In academic circles he is best known for his pioneering work in mathematics, philosophical logic and epistemology. As well as bequeathing several important ideas and theories to later generations of scholars, Russell inaugurated a style of thinking now known as analytic philosophy, which is still taught in most British philosophy departments.

Instead of examining the more technical aspects of Russell's philosophy, this series will focus on issues close to the hearts of How to Believe readers: religion and ethics; the human condition and the modern world; the purpose of philosophy. Russell was gifted writer, and wrote numerous books and pamphlets for a general audience – his History of Western Philosophy is a flawed classic that continues to introduce non-academic readers to philosophy.

Over the coming weeks we will explore Russell's views in some detail. But those views need to be understood in the context of his character, his life and his times – and Russell himself provides a riveting account of these in his autobiography. The first page of this book indicates some of the distinguishing features of his long life: his privilege, his prominence in the public eye, his testing of moral convention. We are introduced to three-year-old Bertrand in the servants' hall at Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park – the home given to his grandparents by Queen Victoria. His parents, recently deceased, had been free-thinkers: his father wrote a lengthy book called An Analysis of Religion, and "all the British philosophers from Mill downwards" were to be found at his mother's London salon. They had left Bertrand and his elder brother, Frank, in the care of two atheist guardians (one of whom had had a relationship with the children's mother), but Chancery awarded custody of the boys to their less radical grandparents.

Young Bertrand showed an early talent for logic when he argued with his grandmother that "it was inconsistent to demand at one and the same time that everybody should be well housed, and yet that no new houses should be built because they were an eyesore." A childhood friend later remembered "Bertie" as "a solemn little boy in a blue velvet suit" who was "always kind". As a young man he so sensitive and timid that when he first stayed in Trinity College, Cambridge for his scholarship examinations he was "too shy to enquire the way to the lavatory, so that [he] walked every morning to the station before the examination began".

Russell insists that he learnt little from his university tutors: "As an undergraduate I was persuaded that the dons were a wholly unnecessary part of the university. I derived no benefits from lectures, and I made a vow to myself that when in due course I became a lecturer I would not suppose that lecturing did any good. I have kept this vow." However, he learned from his student friends to be less solemn, and acquired a sense of humour that, judging from his autobiography, never left him.

Russell's adult life unfolded in a world quite different from the one we know today. For example, in 1910 he was rejected as a Liberal parliamentary candidate because (he suggests) he professed himself an agnostic and refused to attend church occasionally for the sake of respectability. However, in 1949 he was awarded the Order of Merit and in 1950, the Nobel Prize for Literature – which marked, as he puts it, "the apogee of my respectability", and made him feel "slightly uneasy".

After the second world war Russell campaigned for a "world government" to prevent international conflict, and he became increasingly concerned by the threat of nuclear war. In 1955 he wrote a peace manifesto with the support of his friend Albert Einstein, to be signed by leading scientists on both sides of the iron curtain. This document emphasised the need for cooperation between capitalist and communist powers: it led to a series of conferences during the late 50s, and eventually to the 1963 limited test ban treaty forbidding nuclear tests above ground – in space or underwater – in peace time, a "partial ban" that Russell was disappointed with.

These political developments were accompanied by a turn in the cultural tide: the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament was launched in 1958, with Russell as its president. In February 1961 the philosopher, aged 88, joined thousands in a protest march from Trafalgar Square to Whitehall, and pinned a notice on to the door of the Ministry of Defence. Later that year Russell was charged with inciting the public to civil disobedience, and jailed in Brixton prison by a magistrate who told him that he was "old enough to know better".

At the end of his autobiography Russell reflects that since his youth his "serious" life has had two distinct aspects: "I wanted, on the one hand, to find out whether anything could be known; and, on the other hand, to do whatever might be possible toward creating a happier world." Over the hardest decades of the 20th century his optimism and idealism certainly waned, but were not defeated. "I may have thought the road to a world of free and happy human beings shorter than it is proving to be," he concludes, "but I was not wrong in thinking that such a world is possible."