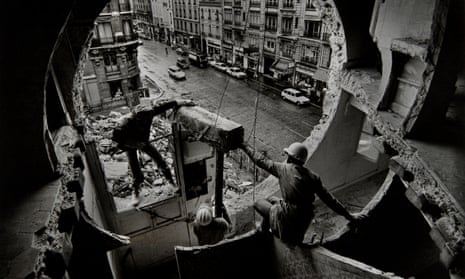

Bare-chested and swinging high on a suspended platform in the vast interior space of a derelict steel-trussed warehouse on a New York pier, Gordon Matta-Clark, acetylene torch in hand, cut into the walls, the floors and the roof, letting the light in. Along with the sparks raining from his torch, the light cascaded from the sky through the building’s empty void to the water beneath. Arcs of light moved with the sun’s passage through the day. The camera filming all this is alternately dazzled and consumed by mysterious gloom. Hidden then exposed, Matta-Clark is glimpsed hard at work, oblivious to the height and the danger, swaying on his little platform.

For three months in 1975 the artist worked, unseen and illegally, in the warehouse. Used by the homeless and by junkies, it was best known for its gay bacchanals on Manhattan’s west-side shore. Now, the pier sits in the shadow of the new Whitney Museum, the whole neighbourhood cleaned up for consumerism and for tourism.

A new exhibition of his career at David Zwirner’s London gallery includes Day’s End, one of several grainy, halting black-and-white films of Matta-Clark’s performative, sometimes illicit and invariably perilous adventures. In perhaps his most famous work, Splitting, from the previous year, we see him cutting through a typical suburban house in New Jersey. The house had been bought as an investment by gallerists Holly and Horace Solomon, but had then been scheduled for demolition as part of an urban renewal scheme. Matta-Clark sawed two parallel cuts, an inch apart, through the exterior and interior walls, the window frames, the roof, floors, staircases and banisters. Sunlight spilled through the gap on to the lawn. Further angled cuts between the ground floor and the stone footings allowed one half of the building to be tilted but remain standing.

The house, Matta-Clark said, “was like a perfect dance partner”, as it shifted and settled at an angle when he pushed it apart. The action reminded him of a silent movie gag. It looks back both to Buster Keaton, and forward to Steve McQueen’s Turner prize-winning 1999 film Deadpan. The more I look, the more I see his influence.

Matta-Clark’s photo-collages of the building are as dizzying as the film. He saw his art as a kind of performance, and wanted to work outside the usual context of art and the art world. Dead in 1978 at the age of 35, from pancreatic cancer, he exemplified a do-it-yourself and go-your-own-way attitude, in part a product of trying to be an artist and wondering what art was for, in a city that was going bankrupt.

He and a group of friends moved into 112 Greene Street in SoHo, and in 1972 opened a restaurant for artists, friends and the local community. The poverty and affordability of the New York neighbourhood presented opportunities – most of all working and living space, the bricolage of materials to be found on the streets, and a sense of artistic community. The result, Food, was at once conceptual artwork, restaurant and laboratory. In reconfiguring and converting the space, Matta-Clark regarded his building work as also part of his larger sculptural practice.

Like a number of other artists, he had gravitated to SoHo long before the galleries moved in, then out again, and before the area teemed with boutiques and coffee shops. In the same neighbourhood, composer Philip Glass was fixing illegal plumbing in empty industrial buildings for artists such as Richard Serra. In retrospect, it feels romantic, a world of opportunities created from difficulties. Even these he itemised humorously in Food’s Family Fiscal Facts, which detailed investment and expenditure, tons of bread consumed and pounds of rabbit stewed, “tortillas pressed and chickens succumbed, lambs led astray, yards of spaghetti steamed (17, 760). Chairs broken, trucks ruined (1) … numbers of cut fingers and cockroaches left lying on the back-room floor.” All are accounted for. This inventory is great fun, as are the menus themselves, featuring duck gumbo, boiled crabs, rabbit with prunes, marrow bones, anchovy and onion pies and “used car stew”. Guest artists, including Joseph Beuys, came and cooked.

Food was as much artwork as restaurant. The rituals of food preparation and eating are the earliest signs of culture and civilisation. Stirring things up, cutting and dividing, mixing and consuming are fundamental in art as in life. Food’s example might lead us toRikrit Taravanija’s communal gallery meals, and to the designation of Ferran Adrià’s Catalonian restaurant El Bulli as an artwork in the 2007 Documenta exhibition.

Whether in New York’s downtown scene, or London’s Hackney and Peckham, artists have become the unwitting pioneers of gentrification. This would perhaps have appalled Matta-Clark, a former architecture student at Cornell University, who railed against both urban blight and soulless city planning, Le Corbusier’s machines for modern living (his father had worked in Corbusier’s Paris office in the 1920s), the machinery of capital and real estate. Matta-Clark styled his own early approach as “anarchitecture”, and he certainly had an anarchic attitude to the built environment, wanting to encourage people to rethink their approach to their surroundings in creative and radical ways.

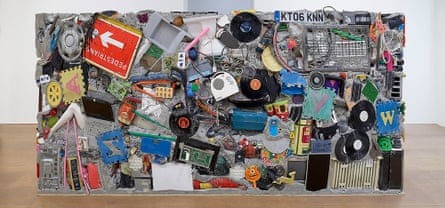

In 1971, Matta-Clark and friends roasted a pig under Brooklyn Bridge, handing out sandwiches, to the music of the Phillip Glass Ensemble. The previous year he had constructed his first garbage wall – mixing trash from the street with concrete, as a possible prototype for walls that the city’s homeless could construct as shelters that were more durable than the layers of cardboard they were using, and still do use, as temporary shelter. While still at Cornell, Matta-Clark had worked as an assistant on a project by artists Robert Smithson and Dennis Oppenheim that inspired both his use of detritus and working outside galleries and other institutions.

The Garbage Wall has been rebuilt many times – including at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds in 2016 – and last week I briefly assisted in the construction of the latest iteration, pushing a busted mobile phone and a child’s plastic sandal down into the still wet, shuttered cement at David Zwirner Gallery. There isn’t much garbage on Mayfair’s pavements, and the plastic and other detritus had to be sourced from further afield.

Matta-Clark wanted, I think, his work to be useful and to delight. Usefulness might be metaphorical as well as practical. He was an artist of his time and place, specifically, the downtown New York art scene of the 70s (a 2011 Barbican exhibition focused on Matta-Clark, Laurie Anderson and the Tricia Brown Dance company) and presaged much of what came later. Matta-Clark’s early death left his art suspended, full of potentials that later artists continue to work with. He continues to be an artist’s artist. McQueen’s Deadpan and the film Drumroll, Rachel Whiteread’s casts of rooms and entire buildings, certain of Tacita Dean’s films all owe something to Matta-Clark’s spirit.

What came to be called relational aesthetics, and artists as diverse as Thomas Hirschhorn and Erik van Lieshout, the socially engaged practice of Theaster Gates, the sliced and rearranged drawings of Roni Horn and the architectural interventions of Richard Wilson all owe a debt to Matta-Clark, just as he was inspired by Vito Acconci, Bruce Nauman, Robert Smithson and Robert Rauschenberg. Nothing comes out of nothing. Cities and circumstance, friendships and contexts are also more than backdrops.

Matta-Clark believed that art in a social context is a generous human act. He also saw it as a measure of freedom in society. He left a large trove of photographs, drawings, notebooks, films and video, which went beyond mere documentation. Much of this work is in this London exhibition – including his drawings of trees, hand-coloured photographs of New York graffiti (he was one of its earliest admirers) and drawings made by cutting through layers of paper. Everything is a trace of his passage, his ideas, his curiosity and enthusiasms.

“Buildings are fixed entities in the minds of most,” he wrote. “The notion of mutable space is virtually taboo – even in one’s own house.” He also said: “I cut through a building for surprise and to transform space into a state of mind.” It was all a lesson in social engagement, play and possibility. He wanted to let the light in.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion