‘Those who want to see art should bypass London and go straight to Glasgow,” wrote the German critic Hermann Muthesius in 1902. “Glasgow’s take on art is unique,” he added. “In architecture, it is a new, young city.”

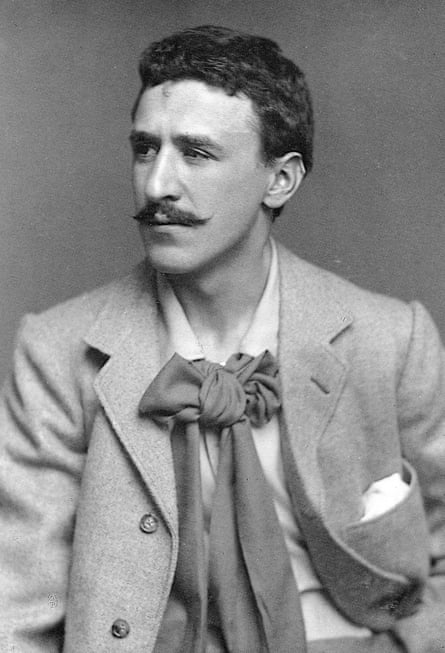

What most caught his eye was the work of a young couple, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his wife, Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh, who were quietly making wildly original furniture, buildings and interiors. These struck him as utterly “divergent from everything that is familiar”. Fusing the sinuous forms of art nouveau with rugged Scots baronial motifs and exotic Japanese touches, their designs were a startling sight – too much for many British critics to stomach.

Generations later, as Glasgow lays on a dizzying roster of events for the 150th anniversary of Mackintosh’s birth on 7 June, it can be difficult to see the work as radical. The world is now awash with Mackintosh mugs, tea-towels, brooches, earrings, cushions and mirrors – a plethora of chintzy merchandise adorned with the trademark floral tendrils and abstract grids. What was once provocative is now the stuff of the gift shop.

“People send me all kinds of horrible ‘Mockintosh’ trinkets because they know I’m a fan,” says Robyne Calvert, Mackintosh research fellow at Glasgow School of Art. “Sometimes they’re described as ‘Renée Mackintosh’, to add an extra exotic ring.” Calvert, who is from Florida, caught her first glimpse of a Mackintosh building during a university lecture – and was so spellbound, she ultimately headed for the source in Glasgow.

When not writing academic papers, she collects instances of Mackintosh designs appearing in popular culture. “There’s something about the work that speaks of sci-fi or steampunk, suggesting a kind of postapocalyptic future,” she says, noting that Mackintosh chairs have appeared in a number of movies and TV shows, including Blade Runner, Doctor Who and Inception.

Calvert was recently surprised to discover that, in the video for Express Yourself, Madonna thrusts her groin into a high-back Mackintosh chair, before crawling beneath a table lined with yet more chairs to lap up a saucer of milk. What might Madonna do if she were let loose in the plush interiors of the newly restored Willow Tea Rooms on Sauchiehall Street, which reopens this month following a £4.5m renovation? The mind boggles.

The culmination of Mackintosh’s work for entrepreneur Kate Cranston, the tea room is the very definition of a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art for which he designed everything from the facade to the cutlery to the waitresses’ uniforms, while Margaret adorned the walls with her sinuous gesso relief panels. Built in 1903, this was a fantasy for the ritual of afternoon tea, with a ladies’ room at the front in white, silver and rose, a darker panelled room at the back lined with oak and grey canvas, and a top-lit gallery held up by great timber posts, like tree trunks rising to a trellis canopy.

Green glass droplets dangled from the stair balustrade, gleaming like the rich fruit of an exotic tree, leading up to the salon de luxe, where punters could pay extra to sit in a sumptuous barrel-vaulted lounge of silk-upholstered walls, purple settees and silver-painted tables with matching high-backed chairs. Compared with the dark Victorian pubs and dining rooms of the time, it was a futuristic wonder.

After years as a department store and jewellery shop, all of this has been recreated, much from scratch, by conservation specialists Simpson and Brown, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund and private donations. It has been a meticulous process, piecing clues together from contemporary photographs, given that few original drawings survive.

The neighbouring building has been transformed into a museum and education centre, where some of the original fittings will be displayed, including the stained-glass doors of the salon de luxe. Now worth £1.5m each, they’re too precious to put back in place.

A similarly forensic re-creation is under way at the school of art, where the famous Mackintosh library is being lovingly rebuilt, after being totally destroyed by a fire in 2014. A detailed survey was undertaken in the 1990s, so master joiners Laurence McIntosh have most of the information they need to recreate the hallowed space. Those who knew it as a dark cave of books might be shocked by the brand new tulipwood that lines the room, a much lighter shade than the almost black beams that used to criss-cross this atmospheric oasis of learning.

The library has been matched to the hue of photographs dating back to 1909, while other rooms in the school, which is not yet open to the public, are returning to curious shades of minty green and rusty red, following months of specialist paint analysis. It won’t be the whitewashed place that people remember, but it is what Mackintosh intended. His penchant for garish colour schemes is revealed in a magnificent exhibition at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery, which takes visitors on an encyclopedic romp through the work of both Mackintoshes, as well as a number of contemporaries and influences of the time.

Seeing their drawings of etiolated figures – half plant, half human, all sinews and tendrils – makes you realise why they were nicknamed the “spook school”. Encountering a phallic stencil from another tea room, you understand why the architect Edwin Lutyens exclaimed after his visit: “The result is gorgeous! And a wee bit vulgar! … It is all quite good, all just a little outre.”

Toshie was never one for half measures. His designs for a basement dug-out at the Willow Tea Rooms (sadly not part of the restoration) depict a jazzy optical art scheme with bright yellow furniture, purple cushions and mesmerising grids covering the walls. “He was producing art deco designs way before art deco came into being,” says curator Alison Brown. “He used Yves Klein blue before Yves Klein was born.”

He was a one-off and consciously so. “Shake off all the props, the props tradition and authority offer you,” he wrote, “and go alone – crawl, stumble, stagger – but go alone.” After being immersed in all the drawings and ephemera at the Kelvingrove, the buildings of Glasgow seem to sing afresh.

Suddenly you notice how the bulbous water tank at the top of the Herald offices (now the Lighthouse centre for architecture and design) is modelled on a thistle; how the sides of the Daily Record building (now home to the Stereo cafe) use glazed white tiles to bounce light into the narrow alleyway; how the Mackintoshes used their own house – today encased in a brutalist tomb at the Hunterian gallery – as a showroom for their latest daring experiments in fittings and furniture.

The school of art is offering walking tours of key works. No one should miss the Mackintosh Church at Queen’s Cross, one of his most intact original buildings. Designed in 1897, it shows the roots of later designs: the side gallery, modelled on a Japanese inn, would influence the art school’s glorious library 10 years on. The church is currently home to an installation, a gigantic inflatable moon that dangles surreally beneath Mackintosh’s great hull-like roof.

Scotland Street School, now a museum marooned on a busy road just south of the Clyde, should not be missed, either, if only to see how the architect always got his way, no matter the wishes of the client or the limits of the budget. Mackintosh was determined to build a glazed turreted castle of a schoolhouse and, despite the protests of the school board at the rising costs, that’s exactly what he created.

His language of abstract botanical motifs is in full flow, with thistle forms on the fence and seed pods at the entrance becoming shoots and blossoming trees as they rise up through the building – watered with knowledge as they climb. These were costly details that the board found “absolutely objectionable”. But Mackintosh, through the deceptive circulation of alternative drawings, got his way. As the uncompromising maestro said: “The artist’s motto should be, ‘I take my stand on what I myself consider my personal ideal.’”

This may partly explain why his architectural career only lasted 12 years, before he moved south and the commissions dried up. But, if you can forget the tea towels, mugs and chintz, what dazzling years they were.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion