If you want to know why the Bayeux tapestry truly matters, why it is one of the world’s great works of art and not just a corny bit of British heritage, the place to start is not the famous scene of Harold getting it in the eye at the Battle of Hastings, or even the wondrous image of Halley’s comet that was embroidered 600 years before Halley, but a far more unsettling detail: a depiction of a war atrocity.

As the Normans establish a beachhead on the south coast, two men are setting fire to a Saxon house. You can tell from their dull disengaged eyes they are only following orders. In front of the blazing building, on a smaller scale than the burly arsonists, a woman holds her boy’s hand as she asks for humanity with a dignified, civilised gesture.

Quick GuideThe Bayeux tapestry

Show

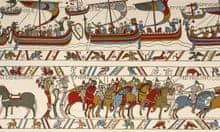

The Bayeux tapestry is a graphic depiction of the Norman buildup to, and success in, the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In a series of scenes told in 70m of coloured embroidery and Latin inscriptions, it shows how William the Conquerer crossed the Channel to seize the English crown from King Harold.

Commissioned by William’s half-brother Odo, it is an early example of history being written, or in this case embroidered, by the victors. It shows vivid and often gory battle scenes between two sides clearly identifiable by their haircuts: the English with shoulder-length hair and moustaches fighting the clean-shaven Normans with short back and sides.

Highlights include an appearance in the sky of Halley’s comet, seen as a bad omen for Harold, William’s dragon-headed ships crossing the sea and the death of Harold after being shot through the eye with an arrow.

The Bayeux tapestry is not just a fascinating document of a decisive battle in British history. It is one of the richest, strangest, most immediate and unexpectedly subtle depictions of war that ever created. That burning house is not the only detail that undercuts the myth of chivalry. At the height of the battle, the lower margin of the 70-metre comic strip – which started out as a parade of bizarre beasts – becomes a carpet of dead bodies, with gorily depicted wounds (one man is headless). Horses are also shown to be war’s victims. As they rush into the fray, two take terrible tumbles, landing on their heads and necks. Another horse runs wild with terror among mutilated human corpses.

Not a single horror of war is hidden. Nor are its little ironies. Bishop Odo of Bayeux, half-brother to William the Conqueror, wades into the heart of the fighting with a huge wooden club. As a churchman he can’t wield a sword, but there’s nothing in the Bible about braining people with oak.

The “pacifist” details in the Bayeux tapestry strike some viewers as so subversive that it must have been made in Britain, by Anglo-Saxon women who filled it with seditious subtexts. That’s a Brexity long shot. The earliest records of the tapestry suggest it has always been in Normandy. Besides, its honesty about war is part of a bigger picture that paints (sorry, stitches) Duke William as a big-hearted, chivalrous hero whose kindness to the Saxon Harold was repaid by betrayal. What lord should do less when his liegeman breaks an oath than build a fleet, kill his enemy and change the course of British history?

The ambivalence of the Bayeux tapestry is what makes it so mysterious and majestic. While its creators will always be anonymous, it surely is the perspective of women embroiderers that helps it see so many sides of this story of the male ego run riot. It is both a propagandist narrative of the Norman conquest and a totally honest exposure of the brutality of battle. Nor is it just black and white – on the contrary, it’s red and yellow, brown and blue, and teeming with details of everyday life: workers building ships and castles, a pack of hunting dogs, chain mail, holy relics, roasting meat.

France’s loan of this mighty thing to Britain is truly generous and exciting. The Bayeux tapestry is much more than a chronicle of faraway events or a symbol of national identity. It is a disarmingly human window on a world that is not so different from ours after all – an age of cruelty and comedy, small pleasures and sudden deaths. Like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, this medieval treasure speaks eloquently to the modern world because it is a true picture of life in all its joy and sorrow. We should be thrilled.