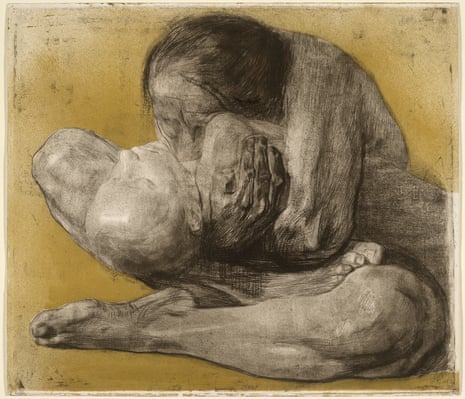

A dead child lies, bone white and fine-featured, between its mother’s thighs. The mother is a hulking creature, something from a nightmare, caught in what is every parent’s worst nightmare. Her body has the heavy muscles of Mary in Michelangelo’s marble Pietà, but here grief has turned her into an animal rather than a saint. Shadows of sorrow spread across her naked limbs. Her mouth is fixed on her child’s chest. She seems to want to suck her offspring back inside her.

There’s no air in Woman With Dead Child, Käthe Kollwitz’s most famous image of war. The picture’s edges press in on its subjects like the mother’s despair. Four different versions form a crescendo of anguish in the final room of Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery, the awful tableaux repeated with varying background tints and denser shadows. I want to make a joke, to relieve this awkward lump in my throat, but there is no room for jokes in Kollwitz.

The prints, part of a show marking the 150th anniversary of Kollwitz’s birth, were created between the end of the 19th century and over the course of two world wars. They contain scores of worn faces, broken backs, hungry, hollow-eyed mobs and sick babies. These are lives she saw first-hand as an artist and doctor’s wife in Berlin’s downtrodden Prenzlauer Berg, an area where cheap labour fed the city’s fast-paced industrialisation. The surgery was in the family house, and so was the studio where she taught herself print-making. It took up less room than painting, which, against the odds as a woman, she had studied.

The granddaughter of a radical Lutheran pastor, Kollwitz was raised on social duty and egalitarianism. It’s the spine of her work, the body of the people being forever abused by the system. In Peasants’ War, one of her print cycles on the theme of revolution, a man is all but reduced to a beast, pulling his plough on all fours. His prone form is echoed by a woman abandoned in leaves nearby, an image of rape. People seem literally stamped down, the earth ready to envelop them.

Such images have all the righteous horror of great protest art. Yet while Kollwitz responded to some of the 20th century’s major upheavals, her sensibility doesn’t quite chime with our own. There is none of the absurdity that lifts Goya’s or Picasso’s takes on old age and war. Her campaigning vision is a black tunnel of mourning. Critics have grumbled about it being one-note. Though she spent her formative months in Paris in the early 1900s, the radicalism of the modernists seems not to have touched her. She is a child of the 19th century, drawn to realist work such as Zola’s novels and printmaker Max Klinger’s urban parables about the woman’s plight.

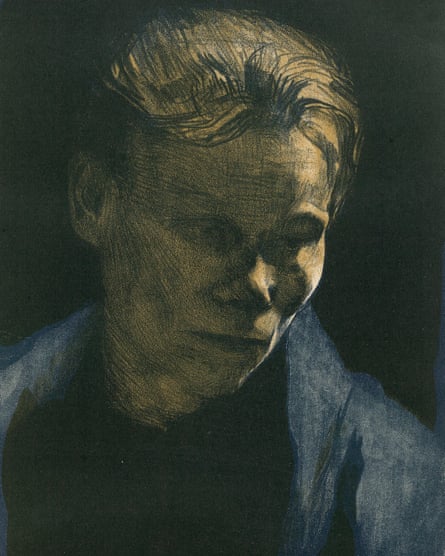

But such questions about her place in art history melt in the face of the work itself. Her portraits of ordinary Prenzlauer Berg women, conjured from scores of expressive lines and smudgy shadows in etchings and lithographs, have the majesty of figures carved in stone, their features chiselled by hard knocks. Staring into the middle distance, their gaze is turned inward on troubles we can only guess at. The triumph is Bust of a Working Woman With Blue Shawl, a Madonna for the industrial age, with shadowed downcast eyes and set mouth.

We meet the artist herself in the first room, as an old woman with a penetrating look to rival Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. Kollwitz was only in her 40s and 50s in many of the careworn images she created of herself, yet the death of her youngest, cherished son Peter had, she believed, left her prematurely aged. He’s the boy model in Woman With Dead Child, lying for hours in her lap while she worked, reassuring her, according to her diaries, that “it will be very beautiful”. It was another 11 years before his terrible death in 1914, shot down as soon as he was sent to the front in the first world war. Too young to enlist without his parents’ permission, he was only able to go after Kollwitz pressed her husband to sign the relevant papers.

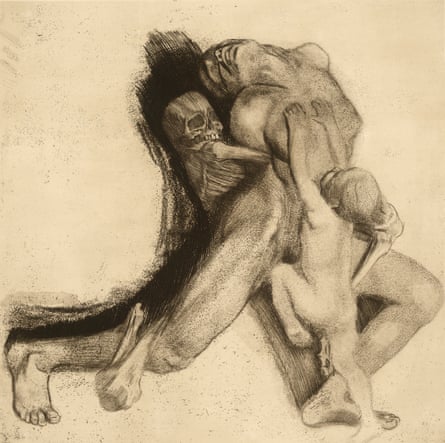

While her son’s end meant her later output was driven by guilt and grief, death was her lifelong creative companion, frequently tearing her work in opposite directions, a thing of arbitrary cruelty and sensual appeal. Its push and pull is given a full-blooded, ghoulish literalism in 1910’s Death and Woman, a creepy gothic threesome where a voluptuous naked mother struggles, apparently in ecstasy, between a skeleton and a baby. The theme got full rein in a late series of lithographs in the 1930s, of which just one telling image is displayed here. It’s a self-portrait: Death’s hand touches the artist’s shoulder and she turns her cheek towards it like an old lover.

- Käthe Kollwitz: Portrait of the Artist is at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, until 27 November.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion