Who would you prefer to have a drink with, Hogarth or Gillray? That may sound like an insanely arcane question, but it’s one that I’ve discussed with other cartoonists on several occasions.

Ours is a small profession, with an exaggerated reverence for its past masters, mostly because we’re always stealing from them. And William Hogarth and James Gillray are, without question, the greatest gods in our firmament. The 20th-century cartoonist David Low, himself now firmly embedded in the pantheon, was bang on when he described them as, respectively, the grandfather and father of the political cartoon.

Things that we’d now call political cartoons – mocking allegorical pictorial representations of public events – have been part of the politics scene since printing. But in the 1730s Hogarth took the form to new heights with “modern moral tales” such as The Rake’s Progress or Marriage à-la-mode. Twenty years after Hogarth’s death, Gillray adapted this general satirical vision (as a student at the Royal Academy schools the young Gillray revered Hogarth’s work) by honing it to what has remained the agenda of political cartoonists ever since: responding to contemporary events in ways that have far more in common with journalism than with what’s commonly called “art”. Between them, Hogarth and Gillray marked out either end of the open sewer of satire that ran through the heart of the Enlightenment.

To a large extent we understand the 18th century through Hogarth and Gillray’s eyes. From a world before photography, it’s Hogarth’s vision of London that has endured, with the savage slapstick of its greater and meaner thoroughfares, its strutting rakes, syphilitic whores, gin-sodden murderers, squashed cats and gallows. Likewise, if we have a visual awareness of Britain’s statesmen from the tail end of that century, it’s probably Gillray’s versions of them: the freckly beanpole Pitt or the spherical Charles James Fox, or Edmund Burke, who Gillray transformed almost beyond recognition into a pointy, interfering nose, a pair of spectacles and – thanks to his Irishness and rumoured Catholicism – a biretta.

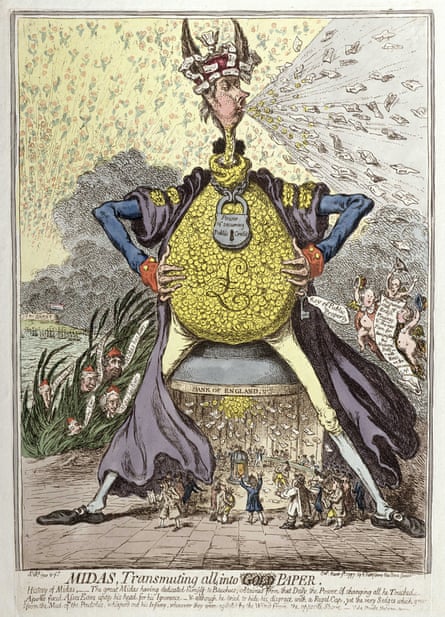

Parallel to that open sewer of satire in Georgian London were real open sewers. A lot of the humour of 18th-century satirists is coloured by the realities of urban living, and the colour is often brown. London was expanding exponentially northwards and westwards, but it was still a city with no flush toilets. No wonder, then, that there’s a kind of faecal satirical trickle-down, from Swift’s scatology, via Hogarth, to Gillray and his contemporaries. In The French Invasion; or John Bull, Bombarding the Bum-Boats, published in 1793 under a pseudonym, Gillray anthropomorphised the map of England into the body of George III, who’s firing turds out of his arse (Portsmouth) on to the French fleet. Likewise, Midas, Transmuting All into Paper, published in 1797, shows William Pitt vomiting bank notes and shitting money into the Bank of England.

This earthiness – “Hogarthian” defines it perfectly – didn’t necessarily age well. Swift’s dark last book of Gulliver’s Travels, which his contemporaries “got” with no trouble, led the Victorians to dismiss him as a deranged misanthrope. Gillray has suffered a similar fate, but the 18th-century audience had stronger stomachs. They had only to walk down the street to find not just shit in the gutters, but around the next corner, a child being publicly executed for stealing a bun. That said, it’s the rawness of their filthiness that makes Gillray and Hogarth far more approachable than many of their contemporaries.

Which gets us to the heart of the beast, and why Gillray in particular, 200 years after his death, still matters. Personally, I believe satire is a survival mechanism to stop us all going mad at the horror and injustice of it all by inducing us to laugh instead of weep. More simply, satire serves to remind those who’ve placed themselves above us that they, like us, shit and they, too, will die. That’s why, if we can, we laugh at both those things, as well as being disgusted and terrified by them. Beneath the veil of humour, there’s always a deep, disturbing darkness.

And that’s why, for my money, Gillray’s greatest print was the one he produced after the battle of Copenhagen, and which appeared at first sight to be a simple piece of jingoist triumphalism: Jack Tar, the naval avatar of John Bull, sits astride the globe, biffing Bonaparte and giving him a bloody nose. The title, though, gives Gillray’s game away. It’s called Fighting for the Dunghill. That interplay between text and image, with irony and nuance undercutting each other, is exactly how a political cartoon should work – and this is why Gillray remains great.

He also matters because he can lay claim to having produced the greatest political cartoon ever in The Plum Pudding in Danger”, which is almost the type specimen of the medium. That’s why it’s been pastiched again and again by the rest of us. In it, Pitt and Bonaparte carve up the world between them in a never-bettered visual allegory for geopolitical struggle. It is, of course, just possible to imagine this being done straight: to conceive of a “serious” artist depicting noble statesmen earnestly if allegorically slicing up a pudding, making the same point as Gillray but with considerably more gravitas. That hypothetical painting, though – I imagine it being about 40ft wide and occupying a whole room in a palace – would have stunk. The power in The Plum Pudding lies entirely in its capacity to make us laugh, which arises from the way Gillray portrays the two great statesmen: Pitt lanky and crafty; Bonaparte short and manic. (In exile on Elba, Napoleon said Gillray’s depictions of him did him more damage than a dozen generals.) Then there’s the plum pudding itself. There’s something deeply preposterous about reducing the titanic struggle for global hegemony to a fight over a dessert. After all, food – like shit – is for some reason always funny. It makes us reflect on the deeper, defining absurdity of two men who imagine that between them they can eat the whole world and everyone in it. The bathos melts inexorably into pathos. That’s what a great political cartoon can do.

So, to get back to that imaginary drink: Hogarth or Gillray? In the past, we’ve always ended up opting for Hogarth. Gillray was without question a genius, but he was also a miserable sod, a quality not uncommon among cartoonists. He died insane as a result of his alcoholism, which got worse when his eyesight started failing. It’s possible he killed himself, following an earlier attempt to throw himself out of the window of the room he occupied above Hannah Humphrey’s Print Shop in St James’s, where the Economist building now stands. His friends described him as “hypy”, neurotically obsessed with his own ill health, while he grew up in the Moravian Church, which seemed to view our earthly existence as a hideous burden to endure before we’re released into eternal life after death – a journey already undertaken by many of Gillray’s siblings in infancy. Add to those factors a career spent transmuting the world’s horror into laughter and it’s no wonder that, like the cartoonists Victor “Vicky” Weisz and Phil May (to name only two), he experienced such a troubled end.

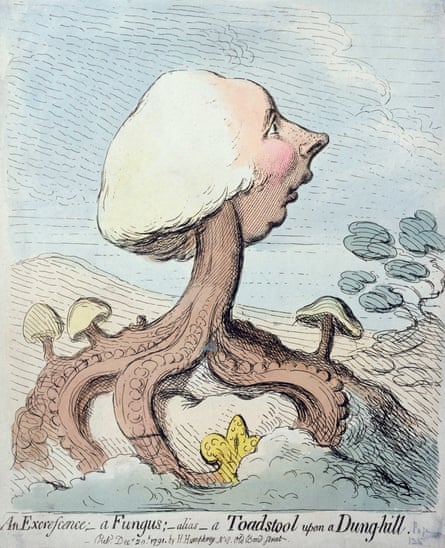

He’s been accused of worse things. A former comment editor on this newspaper, when I was justifying the number of words in a cartoon by citing Gillray, dismissed my argument with: “Gillray was a Tory”. He certainly took a pension from Pitt’s government and produced some embarrassingly propagandist stuff for the ambitious young Tory MP George Canning’s newspaper the Anti-Jacobin. In mitigation for Light Expelling Darkness, an April 1795 print showing a heroic Pitt as Apollo, we should consider Presages of the Millennium from two months later, in which Pitt is skewered ruthlessly as Death on a pale horse – not forgetting the famous 1791 print of Pitt as an Excrescence; – a Fungus; – alias – a Toadstool upon a Dunghill, growing out of the British Crown.

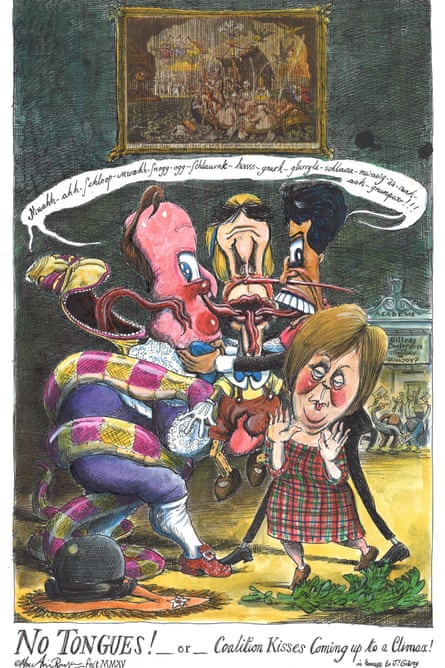

But Gillray even gets damned for his even-handedness. On the 28 and 29 March, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford is hosting a seminar titled “James Gillray@200: Caricaturist Without a Conscience?”. The flier for the event accuses him of being “an unreliable gun for hire” and having “no moral compass”. It also repeats the story about Gillray proposing a toast to the French revolutionary painter Jacques-Louis David at a public dinner – implying the cartoonist then betrayed his revolutionary fervour with his prints attacking the Jacobins, such as the wonderfully overwrought The Apotheosis of Hoche. Well, maybe – though I’ve always suspected what Gillray was actually guilty of was that most indigestible of things for a historian: joking.

And I’m compelled as an act of professional solidarity to say give him a break. Cartoonists aren’t romantic heroes. For the most part we’re just hacks trying to make a living by giving our readers an opportunity for a bit of a giggle. Occasionally something horrific comes along, such as the Charlie Hebdo murders – and there are all the other cartoonists that governments around the world imprison and murder. But whatever the response, we’re still cartoonists, not warriors.

Not that Gillray didn’t have similarly hostile – if less deadly – encounters with the objects of his scorn. The Presentation – or – the Wise Men’s Offering, a 1796 cartoon depicting the Whig opposition led by Fox and Sheridan kissing the bottom of the Prince Regent’s newly born daughter, Princess Charlotte, got Gillray arraigned on a charge of blasphemy. This, remember, was when booksellers risked being transported to Australia if they stocked Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man. In addition to these travails, Gillray had also been courted for months by Canning, who wanted to be included in one of his prints. This alone demonstrates Gillray’s significance, highlighting the perpetual truth that the one thing politicians hate more than being in a cartoon is not being important enough to be in one. As things turned out, Canning got Gillray off, and got him his government pension into the bargain.

But it’s how Gillray repaid this saviour that, for cartoonists at least, is why he should be revered forever. In one of his finest, maddest prints, Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion a sans-culottes army of Jacobins march down Pall Mall as the gutters run with blood. Fox flogs Pitt, a church is set ablaze, and ministers and princes are beheaded and defenestrated. Some have dismissed the print as alarmist Tory propaganda, though to me it looks more like one of Hogarth’s joyously dark carnivalesque scenes at Tyburn. Either way, just visible in the background, hanging from a lamppost and represented in the most demeaning fashion is, of course, Canning himself.

- Love Bites: Caricatures by James Gillray is at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, from 26 March. ashmolean.org.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion