There is something very British about getting the army to blow up a garden shed and then displaying the arrested, flying debris as a work of art, and as a model of the Big Bang at the beginning of the universe. Caught mid-flight, ruptured hot water bottles, gumboots, rakes, hoes, teapots, singed toys, hair-curlers, a mangled copy of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past and the splintered wreckage of the shed itself hang motionless in a simulated freeze-frame, Matrix-style, in mid-air.

Lit by a single light bulb at the explosion’s heart, Cornelia Parker’s 1991 Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View cast mad expressionist shadows round London’s Chisenhale Gallery. It is an explosion that keeps on happening, and here it is again in one of the newly restored and extended spaces at the Whitworth, which reopens on Saturday.

Parker is a good choice. Her work can be intimate as well as spectacular. Even her smallest works can be little mind bombs: a criminal’s sawn-off shotgun, sawn-up again into little chunks by the police; a pile of cocaine incinerated by HM Customs.

Relationships to art, as well as to the larger world, are at the heart of Parker’s project. At the end of a long view, down the newly restored central gallery, sits Rodin’s 1901-4 The Kiss, the two lovers entwined in a mile of string. Parker has put the lovers in delicate bondage. Its not just stone, or love, that keeps them bound. The bare trees of Whitworth Park provide a gorgeous backdrop. At last the gallery has a relationship to the outside world. I’m reminded of the Louisiana Museum outside Copenhagen, and the windows on to the park at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel.

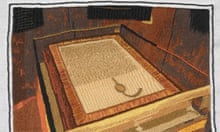

Elsewhere sits another mile of string in a great knotted ball. The string, the caption tells us, was once used to wrap the same Rodin by Parker, but was vandalised by a Stuckist. There’s an unknown object hidden in the ball. Maybe it is a weapon. Parker can turn negatives into positive.

There are dozens of large and smaller works in Parker’s show, each with a complex and allusive back-story. Stories, as well as materials and objects, matter. A new work, War Room, occupies another newly restored gallery, though the space feels like an empty and sinister marquee, lit by four bare hanging light-bulbs. The walls and ceiling of War Room are entirely lined and draped with sheets of blood red paper, the leftover sheets from the factory that makes the 45m Remembrance poppies sold every autumn. The regular stencilled pattern of the cut-out, absent poppies covers the paper. It is a room full of punched-out holes, regular and regimented as a march, or the grid of graves in a Flanders war cemetery. The overall effect is oddly festive, which makes it more disturbing.

Parker’s art really benefits from being seen in all its variety. Full of echoes and correspondences, the turns and returns of her thinking, her show also wanders into the low-ceilinged 1960s galleries, and gives continuity to the Whitworth’s disjointed architecture, its layers of styles and displays. The Whitworth will never fully cohere, but now it is full of surprises, and feels more flexible. We go from dark to light, decade to decade and back again.

In Manchester, Parker has also been working with physicist Sir Konstantin Novoselov, who won the Nobel prize for his groundbreaking work on graphene. Isolating infinitesimally thin layers of graphene from stray crumbs of graphite collected from the margins of drawings by William Blake, Constable and Picasso in the Whitworth’s collection, Parker collaborated with Novoselov to create a breath-activated switch, which will trigger a meteor shower (it’s complicated) on the Whitworth’s opening night.

Upstairs, in an enormous new space, three walls of which are covered in a wallpaper patterned with repeated, photographic motif of breasts (modelled from bent and glued cigarettes), sit several of Sarah Lucas’s distraught figures on chairs. These really benefit from being given lots of dramatic empty space to squirm and flop around in (there’s also a nice contrast and concordance with Parker’s Rodin downstairs). This is a great space for sculpture and – I foresee – for dance and performance.

In the 1960s mezzanine extension, Thomas Schütte’s Low Tide Wandering, a 2001 suite of 139 etchings, hang from bulldog clips on zig-zagging strings, as if they were drying from the press. A diaristic record of the artist’s thoughts; news from a life – and a world – in turmoil.

The Whitworth feels vital and alive, too. Its labyrinthine overlays of galleries, periods and styles begin to make a kind of mad sense. It has lost none of the quirkiness that befits its rag-bag collections nor the different interests of its visitors – whether you want to look at textiles or the collection of wallpapers, 19th-century watercolours or 1960s prints, lovers, shotguns or explosions.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion