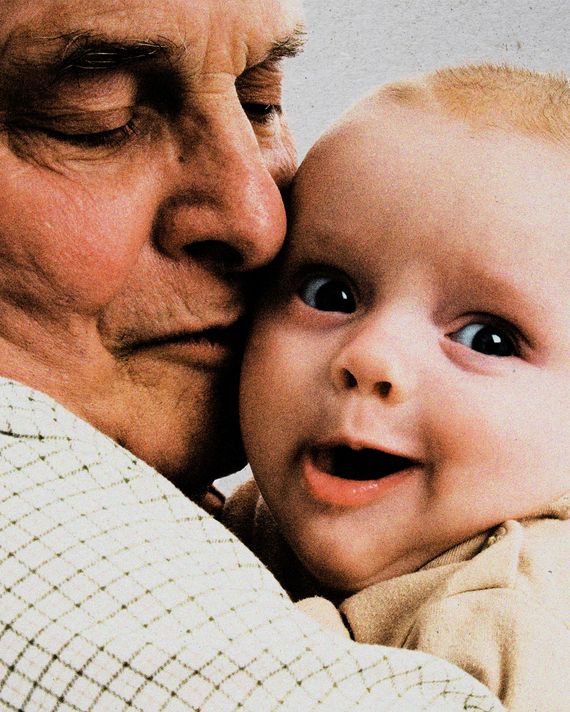

Old dads who are new dads — they’re in the air. This year alone, Robert De Niro, 79, became Dad to a seventh child; Al Pacino, 82, had his fourth kid; and in the Wall Street Journal, Mick Jagger, 80, opined that having young children (his youngest is six) “makes you feel relevant.” There’s even a comedy, literally called Old Dads, coming to Netflix on October 20. (The trailer defines “old dad” as 46, in case you’re wondering who qualifies.) But what of the real-life old dads, walking among us, seemingly unaware that they’re trending?

I had some assumptions about those men. I thought they’d be in a second or third marriage with a grandchild the same age as his newest addition — a May-December situation and presumably a hands-off approach to fatherhood. (As De Niro put it in The Guardian last week: “I don’t do the heavy lifting.”) But then I met Brooklynite Ezra, 72, who welcomed his first child, Joanna, in April 2020, when he was 69. Here’s how he describes his first three years of fatherhood — awkward playground small talk about Woodstock included.

I grew up in New York City in the ’50s and ’60s: I was 18 in the summer of ’69. I spent my 20s working for the state government and decided to go to law school at night in my early 30s. It was almost a given to me that I’d meet someone and have a family, but it didn’t end up happening until I was 43 and almost a decade into my law career. That’s when I met Maria. She was 25 and temping in my office while she looked for a job in publishing. I don’t think either one of us quite realized the other’s age when we started seeing each other. It would have scared me if I knew how young she was. By the time I did know, things were moving pretty fast. We married in 1999 when I was 48 and she was almost 31.

We didn’t really discuss having children before we got married, or even in the first few years afterward. We were both so focused on our careers. I was transitioning into family law, and Maria was finally working at a major publishing house. My sister would say to Maria all the time, “Make me an aunt, make me an aunt.” At some point, Maria was laid off from her publishing job and started freelancing, and I decided to quit my law-firm job and go into practice on my own. I’m typically court-appointed and work on custody and child support cases. Then my sister got sick and passed away after a year of illness. Our lives felt so shaken up. Maria and I were mourning my sister and thinking about what she would have wanted for us. We started talking about trying to have a baby.

We tried and tried and tried. Nobody could tell us what was wrong. We had both gotten pregnant before we met and had ended those pregnancies. Even though I don’t believe in this stuff, I kind of thought it might be karmic payback. But Maria is a very determined person — she has a plan, she effectuates the plan, and she sees it through. She found a doctor who specializes in male fertility. I had a surgical procedure, and we used an egg donor, and then we got pregnant. When she told me, I was floored. We had been trying for 15 years. I was 68 and she was 50.

As happy as we were, we really didn’t tell any friends or family. Maria had a complicated relationship with her family, and my parents had passed away by then. Plus, we’d been trying for so long that there was some superstition that led us to keep the news close. In fact, I didn’t even tell my work colleagues. I knew the baby was coming in April 2020, so I made it a point not to schedule any court appearances for that month. I didn’t give anyone an explanation. Because we told almost no one, we didn’t encounter any questions or judgment about our ages.

But at one point in the pregnancy, we went to a birthing class, and I remember looking around the room at all the young couples and thinking, I feel old. I felt older overnight. I could feel all the aches and pains I’d shrugged off for years. It was like, Oh my God, how am I going to get down on the floor with my kid? Oh my God, how am I going to pick her up when she’s born? I started to really worry about being a dad.

My wife had what’s called a precipitous delivery — extremely quick. Maria’s water broke in our apartment, and we called our neighbor to drive us to the hospital. As soon as we arrived, the hospital staff pulled her onto a gurney and wheeled her into delivery, and by the time I grabbed everything out of the car and got to where she was, she had given birth. When I saw Joanna in her bassinet, I started crying. I don’t know if my wife even knows that. It was April 2020, just a few weeks into the COVID-19 lockdown, and there were a lot of very sick people in the hospital. It was scary and intense. But there she was, and there I was, finally a dad.

We brought Joanna home, and I discovered that my concerns hadn’t been wrong. It was very hard in the beginning. The lack of sleep, the physicality of it. But over time, being on the floor and picking her up and putting her to bed, I actually started to feel more limber than I did that day in the birthing class. Maybe it’s mind over matter.

Maria is the primary caregiver. She’s still freelancing as an editor but does most of her work at night. I’m still practicing family law. I often work from home and can even do court appearances virtually, so if Maria has a meeting or an appointment I can take care of Joanna for a while. Certainly when Joanna was a newborn, I wasn’t sure how to hold her, that kind of thing. I didn’t feel immediately comfortable caring for a baby. But now I feel fully competent. I’m good at this stuff.

My many years in family court have had a big influence on how I parent. My clients all share the same characteristic: It’s very hard for them to put their kids’ needs before their own, and that’s how they end up in court, whether in a custody or child-support dispute, or something else. So I know that my child’s needs come before my own. I guess I always knew that, but now I really Know that with a capital K. One time soon after Joanna was born, Maria said, “You’ve turned into your clients. Your daughter’s needs have to come before your own.” I don’t even remember what it was about — maybe I was focusing on something else when I should have been taking care of Joanna. I thought, You know what? She’s right. I was determined to never have her say that to me again, and so far, I’ve succeeded.

Maria is much better at being a disciplinarian. I’m an early riser, and if Joanna wakes up before Maria I’ll go in and talk with her so Maria can get some more sleep. I really should be making her go pee, but I don’t force it. Joanna can be a little oppositional with us. I just try to talk to her in a way she can understand and spend as much time together as I can. Yesterday, I was on the phone when Maria and Joanna left for the playground, and as soon as I got off the phone, I caught up with them. I have a lot of work to do, but I’m not getting that time at the playground back if I don’t go.

I put Joanna to bed every night. I help her put her pajamas on, get her a cup of water, and let her watch a minute or two of TV. It’s usually either sports or Star Trek. Then we have a goodnight ritual: I’ll say “Goodnight, Joanna. Daddy loves you very much, always.” And then I have to say, “Goodnight, Shaun the Sheep, and goodnight, Abby Cadabby,” because she loves them. And then sometimes she’ll say, “What about Chet and David?” When I was a kid in the ’50s and ’60s, Chet Huntley and David Brinkley were the evening news anchors for NBC, and at the end of their show, they’d say, “Goodnight, Chet,” and, “Goodnight, David.” So sometimes I’ll say, “Goodnight, Chet. Goodnight, David.” And Joanna will say, “Does Daddy love them very much, too?” I’ll say, “Daddy loves everybody very much.”

I’d like to think more life experience has made me a better parent. My parents had very traumatic upbringings — my father was bullied terribly by his father, and my mother was orphaned during the Depression. When I was growing up, they didn’t know what to do if things went off the rails for me. And my mother had a very difficult time spending any money, and that’s something I have to fight against myself. My mother said to me once: “You think we sat around when you were a kid and said, this is how we’re going to screw up our kids? That didn’t happen. But you figure out how to do it anyway in your own way.” So of course, I’d like to think Maria and I are perfect in raising Joanna. But I’m sure we’re not, and we’ll fuck up in our own way.

Still, I know trauma is generational. Therapy has helped me realize the trauma was in my parents’ childhood, not mine. There are things from my childhood I don’t want Joanna to experience, and I hope I can avoid them by making sure she knows she can count on me. I want to be very present in her life — to give her space to try and fail and provide as much support and as many opportunities for her as I can. I want her to know she has options. And if she’s smart enough and wants to go, we’ll figure out how to help her go to an Ivy League school. I never had options like that.

I think about my death more than I ever did before Joanna was born. Now, if an athlete or musician I grew up following dies, it really hits me. David Crosby died earlier this year. He was less than ten years older than me, and when he was gone, I realized I might not have as much time left with Joanna as I wanted. I know Maria and Joanna will be okay financially, although I do keep working so I can save up as much as possible for her education. But I’ll look at Joanna and think, My God, I want 25 more years with her. My father lived until he was 99, so I hope for the best. I’m working on having the best relationship I can with her, and I hope my thoughts of mortality don’t get in the way of my being a dad at all.

It’s comforting to know I’m in good health. We eat organic, lots of whole grains and fish. I ran in the park for years and switched to walking when I needed to. I’ve had knee surgery, and I have plantar fasciitis, but I don’t usually feel my age. Most of my friends are around my age, and even though most of my colleagues are younger than me, I don’t feel older than they are. I don’t think I really look my age either.

I don’t know if the other parents on the playground know how old I am. I have slipped and said something like, “Oh yeah, I didn’t get to go to Woodstock because my ride’s grandmother died the night before we were supposed to leave.” They’ll look at me and say, “Excuse me?!” And I remember one time at dinner with some parent-friends from the neighborhood, people were talking about the Vietnam War. I said, “No, it wasn’t that battle; it was that battle in 1968.” And they looked at me, and I said, “Well, yeah, for you, it’s history. For me, it’s nostalgia.” I haven’t heard any judgmental comments, but frankly if other people think my age is strange, it doesn’t matter to me. That’s something that comes from being older: You just don’t care too much about what other people think. This is who I am.

Does Joanna know that I’m older than most parents of three-year-olds? Not that she’s ever articulated to me. As long as I can keep playing with her, she doesn’t notice. She ran out the door of a store one time, and I ran after her faster than I probably could have 50 years ago.

Of course some part of me wishes it had only taken one or two cycles for us to get pregnant, and we’d have a 15-year-old by now, but that’s not how things played out. And if that’s what it took to make Joanna, that’s what it took.