“I’ve spent my entire career not talking about my personal life,” says Minka Kelly. The actress greets me in West Hollywood and settles into a corner booth of a vegan Mexican restaurant. She’s not necessarily press shy, but she does have a good reason to be reserved. “I have flirted a little bit with sharing things,” she admits, in between sips of iced tea. Throughout her career, whenever interviewers asked about her past, she would deflect with an upbeat attitude, rarely letting on that she endured a messy and mostly bleak upbringing. But there was the time she briefly mentioned in an interview with Cosmopolitan that her mom was a stripper, and she recalls an appearance on The David Letterman Show in 2011, when the host made an off-color joke about her parent. “I was so ill-prepared for those questions,” she says now, shaking her head.

Back then, Kelly was fresh off her breakout role as the rich, popular cheerleader Lyla Garrity on Friday Night Lights and a follow-up gig on Parenthood. Publicly, she was America’s sweetheart, but privately she wasn’t ready to speak so candidly about her dark past. Now, with her new book, Tell Me Everything, Kelly, 42, sets the record straight. She tells us everything.

The compelling 272-page memoir focuses mostly on her hectic and wildly unconventional childhood, couch-surfing as a toddler in Los Angeles, performing at a peep show in high school, and being coerced to make a sex tape as a teen in Albuquerque. She also writes about the time she overheard her mom admit to her boyfriend that she wished she had overdosed, and how that same boyfriend beat her mother with a TV-cable cord. “I have made peace with so much of my past,” Kelly says. But there are flare-ups: “I am so afraid of falling back into my people-pleasing, codependent role that I can sometimes exert my boundaries very strongly,” she warns me. “My girlfriends say to me, ‘We get it, but can you just be a little softer?’”

She had kept those walls up for so long that it wasn’t until somewhat recently when Kelly decided that unearthing a minefield of traumas through autobiography could be a healthy way to unpack what happened to her. “Now I know why I outsource my self-esteem to men and put up with so much shit,” she says, relaying what she learned about herself through recounting her past for her book. “I have this high pain threshold. I re-create dysfunction in my life because that’s what’s familiar to me.”

Seeing her statuesque mom rely on her physicality to make a living also became overly familiar — as well as a cautionary tale. “I watched her looks fade, and she couldn’t be onstage anymore,” Kelly recalls of her mother’s work transition from dancer to bartender and then, finally, to painting nipples on sex dolls. “I went to surgical nursing school, so I wouldn’t fear aging or my worth slipping away,” Kelly says. And while she has consistently appeared in films and on TV shows like HBO’s Titans since her start, Kelly, who bootstrapped her way to fame, has options beyond fickle Hollywood. A decade ago, she took a “break from the business” and went to culinary school for six months. A couple years later, a friend suggested she should write her story down in a book.

In the weeks leading up to the memoir’s release, tabloids have latched onto traumatic experiences, like Kelly’s teenage abortion or her high-school boyfriend’s predatory behavior. But those are just fractions of the narrative. Tell Me Everything is really a tough-love letter to Minka’s mom, Maureen “Mo” Dumont Kelly, a long-legged, bighearted, and hard-partying woman whose addiction made responsible parenting impossible. At one point, the two lived in a 125-foot storage room festooned with Christmas lights. (“Now, I can make a home out of anywhere. My past has made me very resilient.”) Maureen died of colon cancer at 51 in 2008, and Kelly grappled mightily with the complicated grief that comes with mourning someone so dysfunctional. “I’ve accepted that it’s okay to be relieved she’s gone. She doesn’t have to struggle anymore. She’s free,” she says now. Kelly’s French father, former Aerosmith guitarist Rick Dufay, helped her reckon with that relief. “He gave me that permission. It’s actually healthy, right?”

There’s a trend in celebrity narratives that delve deep into abuse, harassment, and the subsequent shame. Think recent tell-alls from Paris Hilton, Emily Ratajkowski, and Constance Wu. And just last summer, former Nickelodeon star Jennette McCurdy sort of echoed Kelly’s experience with her explosive memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died. (For the record, Kelly’s mom wasn’t a stage mother like McCurdy’s.) But for all the complicated memories she may have, Kelly is still quick to fiercely defend her mother: “I felt cherished and adored by my mom. She’s just another person who wasn’t loved the way she deserved to be.”

In order for Kelly to unfurl her own wounded psyche and warped past, she had to escape the artifice of L.A. After all, this is where she learned to act, onscreen and off: “I dressed nice. I took care of myself. I pretended that everything was perfect. My therapist was like, ‘You’re working so hard to prove to everyone that you’re not a stripper’s daughter. Stop it.’”

Thus, Kelly wrote most of her book in Brooklyn. “New York is a city that demands truth. There is no tolerance for bullshit,” she says of the year she spent in Fort Greene, oversharing with her neighborhood girlfriends. Her townhouse was known as “the healing nest” because everyone gathered there to roost and share space. Her house in Los Angeles has the same vibe, but she notes that women in Hollywood can be woefully transactional about confessions. “There were a lot of instances in L.A. with women where I would say something and walk away thinking, Are they going to use that against me?” Kelly says. “Women in New York share back, so you feel safe.”

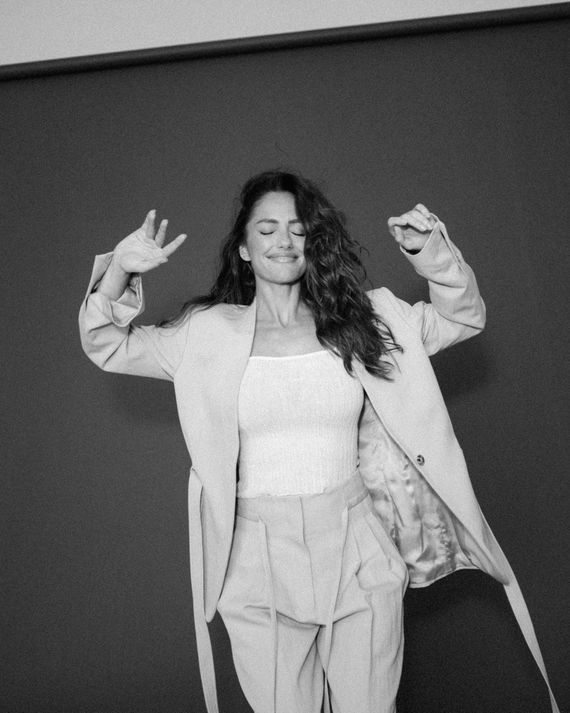

It should be noted that I’m from Queens and opened up like a cheap lawn chair during our chat. And unlike most celebrities, Kelly gets tired of her own voice. She leans in closer. She makes soulful eye contact. She asks questions. She’s dressed inconspicuously in baggy boyfriend jeans, and an oversize white sweatshirt, accessorized with checkered Vans. (Her $1,450 purple Loewe handbag is the only tell that Kelly is an actress who has worked steadily for almost two decades, including a recent stint on Euphoria.) Over an hour or so, we exchange notes on everything from lifting weights to roasting chicken to doing ayahuasca. (“I asked to be shown my divine feminine power because I had made myself small for so long,” she says. “It was a beautiful experience.”)

Kelly also makes it abundantly clear in our conversation — and a follow-up phone call a couple weeks later — that she doesn’t see herself as a victim. She’s not seeking any sympathy either. “I decided to tell my story because the media has written a narrative of me, based on the men they have seen me with, whether I’ve dated them or not,” she says of a list of exes — which includes Derek Jeter, Chris Evans, and Trevor Noah — that prompts headlines that rarely respect her privacy and pushes an agenda that commends her for hooking up with boldface names. (Case in point: The Cut’s own recent callout, “Is Minka Kelly Dating the Imagine Dragons Guy?”) “If you’re going to have an opinion of me, you may as well have the whole picture,” she adds.

But it’s talk around her longing to be a mom and a past miscarriage that punctuates her willingness to reveal herself: “My whole life led to this moment. I’m going to be a mommy, right? And then it left my body and was gone just like that,” she says. “But I do wonder if breaking generational patterns means ending them with me?” That notion lingers in the air for a moment, like the acrid scent of burnt coffee. Kelly squints but doesn’t squirm. “I’ve sort of let go of trying to figure it all out,” she concludes. “Sometimes we don’t have to make meaning of our suffering. It’s just part of life and it fucking sucks and you accept it.”

Clearly, Kelly could take on David Letterman if he still had a late-night show. And she knows opening that window again will let in people who just want the sordid headlines. “Healing doesn’t sell,” she says. But even if Kelly didn’t initially intend for Tell Me Everything to be a self-help book, she now hopes this project could be a salve to lots of “wounded inner children,” the folks to whom she dedicates her book, and she’s already received plenty of positive messages from readers who can relate: “I met a girl at a party the other night who was like, ‘My mom was a stripper too!’”