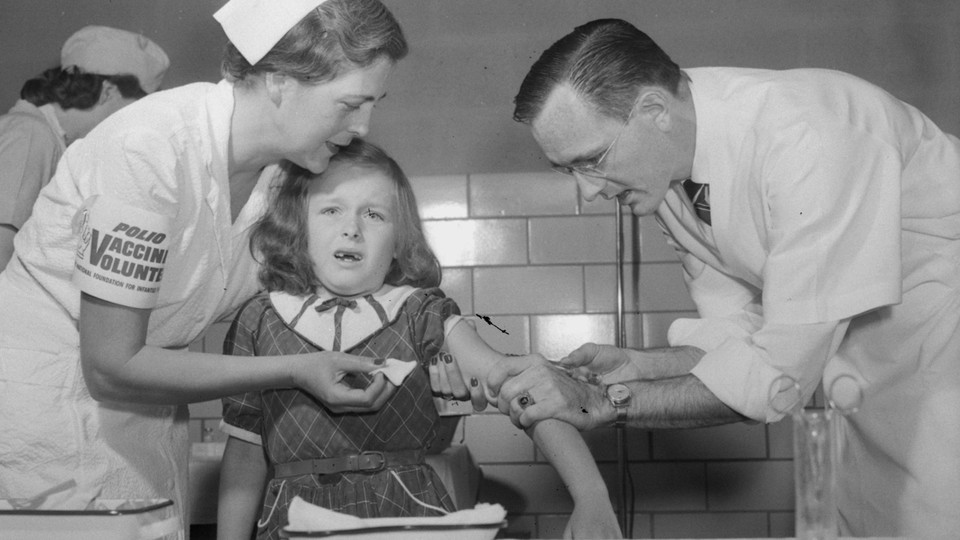

How Good Is the Polio Vaccine?

Ever since the dramatic proclamation of the Salk vaccine, Americans have been asking, What will this do for my child? Can I trust it? These are the questions which Dr. Rustein sets out to answer.

Polio, the familiar term for the disease of the nervous system medically known as anterior poliomyelitis, is caused by a tiny living particle—a virus. Polio has its peak occurrence each summer, when parents anxiously note the location of each new case. In the past they have stood by helplessly when the disease struck nearby, watching through the passing months to learn whether this was a "polio year" in their town or state and breathing easily only when cold weather came.

Not until 1949, when Professor John Enders made his Nobel prize-winning discovery of a method of growing polio virus in large amounts in the laboratory, did the possibility of preventing the disease through the use of a vaccine become real.

When a living polio virus invades the body, depending upon the amount of the virus and the immunity of the individual, it may or may not cause polio. But it usually does stimulate the production of protective substances or antibodies. Living viruses can be changed into vaccines, which should stimulate the production of' antibodies and never cause illness. Changing a living virulent virus into a "killed" vaccine requires the addition of a substance which will destroy the sickness-producing effect without blocking the production of protective substances in the vaccinated child. This principle was applied in the development of the Salk vaccine, which is made by the addition of formalin (formaldehyde) to living polio virus. Since the Salk vaccine was first proposed, many claims have been made for it, and it has at times been the subject of public controversy. Now, after almost three years of experience, it is possible to look at the record and come to some firm conclusions about it.

In the United States in the-first forty-nine weeks of 1956, 15,128 cases of polio were reported to the Public Health Service. In 1955 over the corresponding period there were almost twice as many cases—28,816. This sharp decrease took place during the mass polio vaccination program which was begun in April, 1955. First young school children and pregnant women, and later older children and young adults, were given one to three injections of polio vaccine. At the beginning of the polio season in the early summer of 1956, it was estimated by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis that thirty million people, mostly children, had received one or more injections of polio vaccine. That estimate had to be based on the enormous number of bottles of vaccine distributed by vaccine manufacturers and not on the number of persons actually vaccinated. At the beginning of the program carefully planned records were kept by Health Departments of all those vaccinated under their auspices. But when the program was changed to include over-the-counter sales of vaccine to private physicians, such records no longer included all of those vaccinated.

The marked drop in reported polio cases from 1955 to 1956 might provide final proof of the value of the vaccine if the number of polio cases in each of the previous years had been relatively constant. As seen in the first diagram, this is not the case. There have been wide swings in the number of polio cases from year to year. Beginning in the 1930s, when reports of polio became fairly reliable, there were a number of years—particularly in the late thirties when there were many fewer cases than in 1956. Following this period, there was a rise in the early 1940s, particularly in 1944 when 19,029 cases were reported. In 1947, for no apparent reason, there was a sharp drop to about 10,000 cases. After that, there were a number of "high polio years" reaching a peak in 1952 with 57,879 cases, which was followed by a drop-off to about half that number in 1955. These fluctuations in the number of cases per year have no known explanation and occur not only in the United States but in many parts of the world. It is of interest that a sharp drop also occurred in England and Wales in these same two years, 1955 and 1956, even though in those countries only 200,000 children had received but one or two injections in a program which began in the late spring of 1956. It is, therefore, impossible to tell whether the decrease from 1955 to 1956 in the United States is a result of the polio vaccine program or whether it is just another sharp swing in the usual pattern of the disease.

The total number of cases of polio reported each year includes both paralytic and nonparalytic forms of the disease. When polio occurs without paralysis, it may be difficult to diagnose, particularly in the absence of an epidemic. Nonparalytic polio has to be differentiated from infections due to other viruses, a distinction which medical advances have made possible only during the past few years. When such other virus infections are recognized in epidemic form, as occurred in Iowa in 1956, these cases are properly not included in the total annual figure for polio. Improvement in diagnosis has tended to decrease the number of reported cases of nonparalytic polio in recent years. This in turn makes comparisons of total cases in recent years with previous years less reliable.

Paralytic cases, however, are easily recognized, and paralysis only rarely occurs in other infectious diseases. Thus the total number of paralyzed cases is more reliable for year-to-year comparison. When the paralytic cases to December for 1955 and 1956 are compared, the decrease is much smaller than that of the total cases. There was a drop from 10,405 paralytic cases in 1955 to 6565 in 1956, a decrease of about one third, although there is a possible 5 to 10 per cent error here because of incomplete reports. Reliable records on numbers of paralytic cases for the United States are available for only the last two or three years, and they are, therefore, not precisely helpful at this time in interpreting the sharp decrease of this year. However, the seriousness of the paralytic disease and the reliability of reports on such cases will make this the best index for measuring the effect of polio vaccine in the future.

We are encouraged that in 1956 there was only one epidemic in a major American city, Chicago. This Chicago epidemic was accompanied by an increase in polio in surrounding Cook County and northern Illinois, but this, as well as the other state epidemic in 1956, in Louisiana, was definitely smaller than the most serious epidemics of previous years. It is quite possible that polio vaccination completed before the beginning of the 1956 polio season had something to do with the smaller size. of these epidemics. In future years, if the most serious epidemics continue to decrease in size, this will also be an important index of the value of the vaccine. On the other hand, the intense polio vaccination campaign begun after the start of the epidemic in Chicago had no effect on the course of that epidemic. As can be seen in the second diagram, the upswings and downswings on the epidemic curve are of the same shape, and balance each other as is usual in this disease. If the vaccine given after the start of the epidemic had had a real effect on it, there ought to have been a sharp drop in the number of cases, and the downswing of the curve in the diagram would have been a straight line. One can not expect that polio vaccine given after the start of an epidemic would make any real difference in that particular outbreak of disease, because once an epidemic has started, there is not sufficient time for the vaccine to develop enough protective antibodies in those exposed to the disease.

Complicated comparisons of total and paralytic cases and of epidemics of polio from year to year would be completely unnecessary if it could be shown that children who had received complete vaccination—three polio vaccine injections at the recommended time intervals—would not be seriously attacked by this disease. Unfortunately, this is not so. In 1956 there were over one hundred vaccine failures reported from various parts of the United States. Some of these patients have had severe paralysis and at least two have died. Since there is no way of counting the number of children who had complete vaccinations by the beginning of the 1956 polio season, it is impossible to tell how important this group of cases really is in evaluating the effect of the vaccine.

The early experiments in 1954 and 1955 had already shown that the vaccine was not 100 per cent effective. In 1954, using the original Salk vaccine, the controlled field trial reported by Dr. Thomas Francis showed that the vaccine protected some children against disease from all three polio virus types, including the most common epidemic type, Type 1. In that study, one half of a group of children received polio vaccine and the other half were injected with material which looked the same but which contained no vaccine. For the important Type 1, the vaccinated group had 65 per cent fewer cases of polio than those receiving the dummy material. In 1955, when the vaccine was distributed only through State Health Departments in such states as New York and Massachusetts, it was still possible to separate the children who had been vaccinated from those who had not, and here again, the vaccine was beneficial. The decrease in paralytic cases of Type 1 varied in these studies from 80 to 75 per cent.

Theoretical objections have been raised against the design of these studies, which may decrease these percentage differences. There can be no doubt that there has been definite benefit, but not complete protection. These results were obtained with the original Salk vaccine, and its lack of uniformity was confirmed in animal experiments at the laboratories of the New York State Department of Health. In these experiments, certain batches did not produce antibodies upon injection in animals.

The results from the original Salk vaccine are not entirely applicable today because the method of manufacture of the vaccine has been changed. Modifications were introduced after the original vaccine was found to be unsafe when certain batches caused cases of polio in the "Cutter incident." There have been no proven cases of polio caused by the new batches of vaccine distributed since November, 1955. The questionable cases have been relatively few in comparison with the large number of children vaccinated, and the modified vaccine has been safe for all practical purposes. But the changes in vaccine manufacture included, among others, the filtering out of the larger particles in the vaccine solution, thereby probably decreasing the potency of the vaccine—that is, its ability to produce antibodies in vaccinated individuals.

This decreased potency was demonstrated at the Cook County laboratories in Chicago where it was found that approximately one quarter of a large group of children given the modified polio vaccine did not produce antibodies to the most important epidemic type of polio—Type 1. Moreover, those developing immunity had a much lower level of antibodies than were obtained by Salk with the original vaccine in children of the same age group. Therefore the lots of modified vaccine might be expected not to produce as good results in the prevention of polio as those reported for 1954 and 1955.

On the other hand, it is possible to interpret the Chicago results as due to the inability of certain children to make antibodies even with a good lot of vaccine, but in a study in Galveston, Texas, one particular batch of vaccine was uniformly effective in producing antibodies in children. This evidence would support the conclusion that although some children may be unable to make antibodies, it is more likely that most of the vaccine failures are due to poor batches of the vaccine used.

The only way to be certain that every batch of vaccine will be effective is to measure antibodies produced in a group of children before the batch is released for general distribution. This procedure should be added to present testing methods. If a batch proves to be good, the test group of children will have been immunized. If a batch proves ineffective, these children can then be reinjected with vaccine from a good batch. Such a testing procedure will identify poor batches of vaccine and eliminate their use in polio vaccination. This procedure has been followed before in the testing of gamma globulin for the prevention of measles.

Like certain other infectious diseases—diphtheria, for example—polio is acquired not only by direct contact with the sick patient but more frequently as a result of contact with healthy carriers of the virulent virus or germ. Such carriers, infected by contact with a victim of the disease or another carrier, although having no symptoms themselves, may make others sick by passing the infectious agent to them. The success of diphtheria vaccine is dependent in part on its ability to decrease the number of healthy carriers of that germ. If a virulent diphtheria germ enters the throat of an immunized child, it is not so likely to live and grow as it would if the child were not immune. A vaccination program in diphtheria protects the vaccinated child and decreases the number of carriers in the community, thereby decreasing the number of children infected by coming in contact with such carriers. Vaccinating a child against diphtheria thus not only protects him but also to a certain extent protects nonimmune children in the same community by cutting down their exposure to the germ. When polio occurs, many of those who are in close contact with the patient—his family and his friends—become carriers of virulent polio virus in their gastrointestinal tracts. Such carriers probably play an important role in the transmission of this disease. It was hoped that polio vaccination would decrease the number of such healthy carriers and thus interfere with the transmission of the disease. Unfortunately, evidence being accumulated in four different laboratories indicates that it does not. All the evidence collected so far indicates that children immunized with polio vaccine are as likely to carry the living polio virus as are unvaccinated children. Polio vaccination, then, unlike diphtheria vaccination, can only protect the vaccinated person. Therefore, even if polio vaccination were 100 per cent effective, every person would have to be vaccinated in order to control the disease completely.

The practical problem of immunizing every person in the country is enormous and is further complicated by the need for constantly maintaining a high level of immunization in every individual. The question therefore arises: What is the duration of immunity, assuming that polio vaccination has been effective? In no disease is there permanent immunity after original vaccination. Even where vaccination is highly effective, as in smallpox, it lasts a relatively short time. Our government requires that those traveling to foreign countries show evidence that they have had successful smallpox vaccination within three years before they can be readmitted to the United States. In polio immunization we must be sure, above all, that we are not postponing the occurrence of the disease from early childhood to later in life when it is more serious. Paralysis is more severe and death more frequent when the disease strikes in adult life than in childhood. There is no solid evidence at this time concerning the duration of effective polio vaccination because so little time has elapsed since the beginning of the vaccination program. If the polio immunization program continues to be accompanied by a decreasing number of cases, research on the duration of protection from vaccination must be intensified to determine the time when booster doses of vaccine will have to be given.

The evidence that the presently available polio vaccine does not decrease the number of carriers, and the clear-cut vaccine failures, make it apparent that polio will not be eradicated by this means. Unless the Salk vaccine can be improved, other kinds of vaccine must be developed. At this time, there are two promising lines of investigation. Search must be continued for a virus-killing substance better than formalin to assure a safe vaccine of consistently high potency. Substances such as beta propiolactone have produced in animal experiments effective and safe vaccines with viruses such as that of rabies. Ultraviolet irradiation, which is being used in combination with formalin by one vaccine manufacturer, deserves further study.

The other line of research is the development of live-virus vaccines. This involves converting a virulent live polio virus into a nonvirulent one by successive transfer through laboratory animals. In the hands of Sabin in Cincinnati and of Koprowski in Pearl River, New York, such avirulent strains when given by mouth have produced immunity in children without causing disease. But before widespread use of living vaccine can be made, much work remains to be done. We must be sure that these living strains will not revert to their original virulent form. Another theoretical possibility previously successful in another virus disease—yellow fever—is the discovery of a benign strain of living polio virus which may be safely injected and yet produce effective polio immunization.

Summarizing the evidence through the autumn of 1956, we can 'draw the following conclusions: --

The modified polio vaccine manufactured and distributed after November, 1955, has been safe for all practical purposes, but varies from batch to batch in its ability to produce protective substances.

The failure of this vaccine to prevent disease and at times death in certain vaccinated individuals and its apparent inability to reduce the number of carriers clearly indicate that polio will not be "wiped out" by this vaccine.

It is impossible to tell how much of the 1956 decrease in reported cases of polio in the United States is due to polio vaccination, but it is likely that some of it is due to the vaccine.

For purposes of future planning, it would seem reasonable to assume that the polio vaccine has been effective in producing a decrease in the number of cases of polio in the United States in 1956. The following points, therefore, are clear: --

1. The polio immunization program should be expanded and continued as long as there is a continuing decrease in the number of reported cases of paralytic polio in the United States.

2. Any upswing in the number of such cases must demand a complete revaluation of the entire program.

3. To maintain a high level of protection in those successfully immunized with the present polio vaccine, it is imperative to determine when booster doses of vaccine will be necessary.

4. Lack of uniform potency of the present vaccine demands its improvement or the development of better "killed" or "living virus" vaccines.

We must maintain an objective attitude in the interpretation of results; we must not relinquish opportunities to improve on present methods and to utilize other means which may prove to be more effective in the conquest of polio.