Brezhnev's Secret Pledge to 'Do Everything We Can' to Reelect Gerald Ford

As the Cold War raged in 1975, a Russian leader promised his support for a president’s reelection bid.

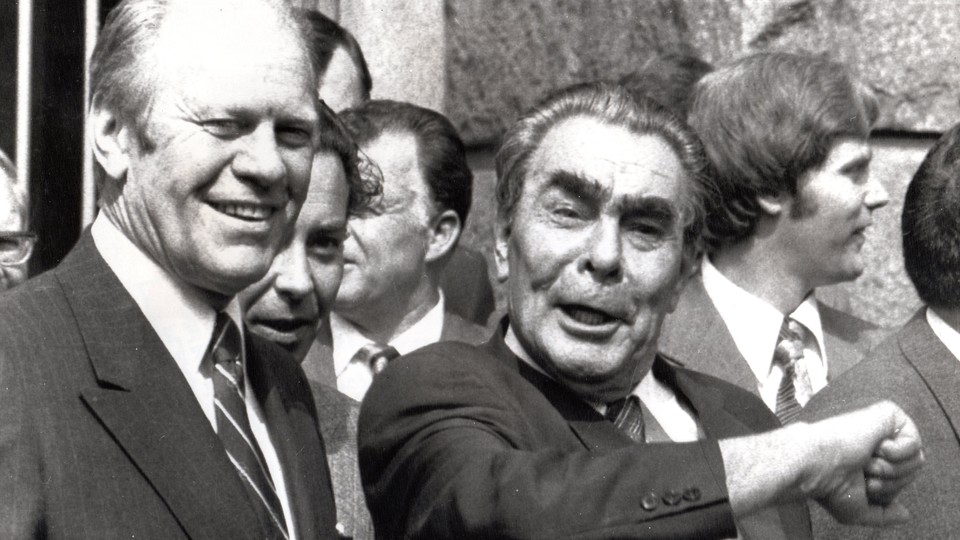

Putin’s covert support for Donald Trump has not been the first time Russia aspired to influence an American presidential election. Forty-two years ago, a Russian leader privately pledged his government’s support for a president’s reelection: “We for our part will do everything we can to make that happen,” Leonid Brezhnev said to Gerald Ford. I know, because I’m the last surviving participant in those events.

In August 1975, President Gerald Ford travelled to Helsinki to participate in the largest summit of world leaders ever held: 35 European heads of state meeting to sign the Helsinki Accords at the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe Summit. The Accords are the only official written settlement of World War II. Russia wanted the agreement because it seemed to ratify its expanded boundaries. In return, the West extracted a prohibition against any future changing of borders by force (which, ironically, Russia became the only state to violate when it annexed Crimea from Ukraine in 2014). The West also got Russia’s commitment to loosen access to western media and to observe its own citizens’ human rights, provisions which became something of a turning point in overcoming Soviet oppression.

I was a member of President Ford’s small policy team in Helsinki. My main role was as the arms-control expert. While the Helsinki conference did not play a large role in arms control, we had scheduled two bilateral side meetings with Russia’s leader, Leonid Brezhnev, to work on a second Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT II). I had been at the initial SALT II discussions with Ford and Brezhnev in Vladivostok nine months earlier and had led interagency preparations within the U.S. government for this follow-on.

Our first bilateral meeting was held at the U.S. Embassy. At the end of the meeting, Ford and Brezhnev left together by way of the front door where they appeared to exchange pleasantries. The rest of us piled into our motorcade and headed for Finlandia Hall where the Summit was being held.

The scene in the hall was astounding. During breaks, one would encounter various Cold War and western European leaders in the hallways. I remember particularly Tito with his badly dyed hair; the Polish leader Eduard Gierek looking appropriately glum; the Romanian anti-Russian communist Nicolai Ceauscsau (later executed); the Swedish anti-American socialist leader Olof Palme (later assassinated), and France’s Valery Giscard d’Estaing, elegant as expected.

The relatively small size of the iconic hall and the need to accommodate 35 heads of state and their staff meant that delegations were placed in close proximity. Our delegation was seated in the center of the main section, just across the aisle from the Soviets. Each delegate was given a small writing desk. It was intimate, requiring us to protect any classified information at our tables. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger created something of a media sensation when his attention to security lapsed and an Italian photographer got a snapshot of one of his secret documents.

I could not help keeping an eye on Brezhnev, taking note of whom he talked to and what he was up to. At one point, I noticed him reaching into his pocket for what turned out to be a pill. Our intelligence services had suspected that Brezhnev had serious health problems—he was a heavy smoker and had begun to look and act weaker. So I took note of what he did with the pill’s wrapper—he put it in his ashtray. If we could determine the medicine in the wrapper, perhaps we could infer his ailments. So I decided to look for on opportunity to get the wrapper.

Victor Sukhodrev, Brezhnev’s interpreter, surprised us when he arrived and pushed his way up to Brezhnev. Sukhodrev was considered by both American officials and the Soviets to be the best Russian-English interpreter in the world. He could not only handle all idiomatic expressions, but understood them in the various “dialects” of English—American, British, Scottish, Australian, Canadian, etc. He had a prolific memory—we witnessed him take only a few notes when Brezhnev would talk for upwards of 20 minutes straight and then offer a perfect English rendering. And he could translate “both ways” (Russian to English, English to Russian) seemingly non-stop. Sukhodrev had done all the interpretation at our bilateral embassy meeting.

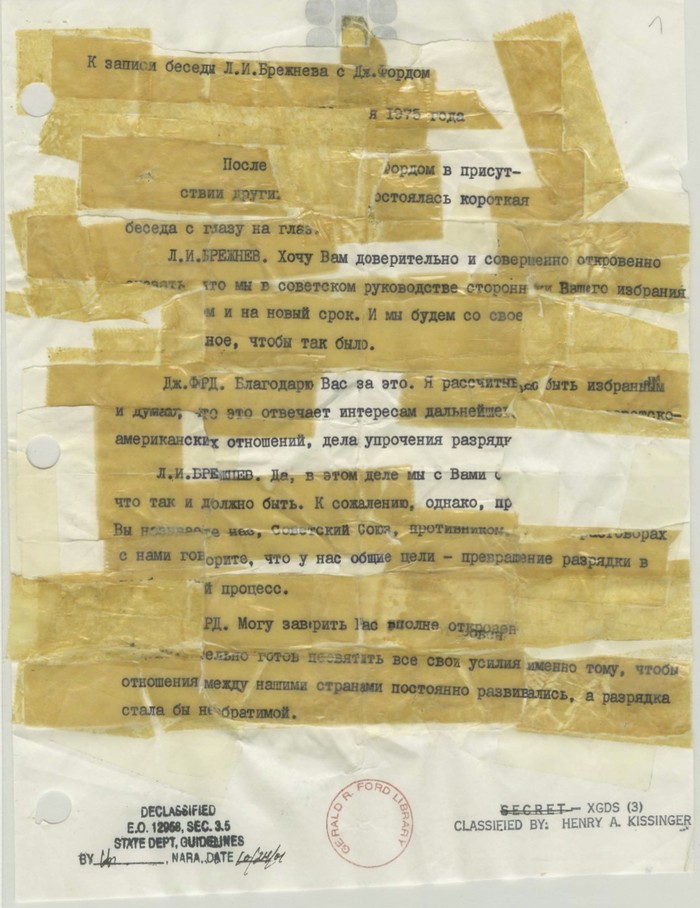

Sukhodrev handed Brezhnev a single typewritten sheet of paper. I inferred that Brezhnev wanted to see the record of something discussed in our Embassy meeting. Brezhnev studied the paper carefully, waved Sukhodrev off, and then did something very surprising—he tore the paper into pieces and placed them in his ashtray where he had put the pill wrapper.

My curiosity was now piqued. So when the session of speeches ended, I carefully took my time organizing the papers at my small table as I watched the Soviet delegation file out. The straightest line to the door was through their now empty seating area, which gave me a chance to empty Brezhnev’s ashtray into my pocket.

Back at the hotel, I gave the pill wrapper to an appropriate member of our team (it turned out not to have anything traceable on it) and tracked down Peter Rodman, Kissinger’s amanuensis and close confidant. I wanted Peter to help me figure out what I had retrieved. We each knew the Cyrillic alphabet and a bit of Russian, so between us we taped the pieces together and worked out a rough translation.

The document turned out to be a verbatim record of a short conversation between President Ford and Brezhnev held on the front porch our embassy as we had departed the bilateral meeting. Only Sukhodrev, Brezhnev, and Ford had been present. Sukhodrev had brought the transcript directly to Brezhnev.

Peter Rodman and I pieced together our rough translation. We were astounded by what we read. (What follows is the official American translation of the exchange):

Brezhnev: I wish to tell you confidentially and completely frankly that we in the Soviet leadership are supporters of your election as president to a new term as well. And we for our part will do everything we can to make that happen.

Ford: I thank you for that. I expect to be elected and I think that that meets the interests of the further development of Soviet-American relations, and of the cause of strengthening détente.

Brezhnev: Yes, on this matter we agree with you that this is precisely how it should be. Unfortunately, however, publicly you call us, the Soviet Union, adversaries, and in your conversations with us you say that we have common goals—transformation of détente into an irreversible process.

Ford: I can assure you, in full frankness, that I am absolutely prepared to dedicate all my efforts precisely to ensuring that relations between our countries develop steadily, and that détente becomes irreversible.

Rodman and I discussed what to do with our discovery. Only the two of us—plus Sukhodrev, Brezhnev, and Ford—knew what had transpired. We decided that given the unusual way the record of the conversation had come into our hands and its private and seemingly social nature, we would not pass it on to anyone else. So I put the only copy, taped together, in my office file and forgot about it.

A few months later, I left the NSC to return to private life. At that point, I made inquiries concerning what I should do with my office files. I was told that the right step, especially in light of the recently passed Presidential Papers Act designed to make sure anything related to Nixon would survive, was to donate them to the National Archives, to be included in the Gerald Ford Library collection. So that’s what I did.

But now we have the Trump campaign’s alleged election collusion with Russia. This triggered my memory of Brezhnev and Ford’s conversation 42 years earlier. So I decided to see if I could get a copy of it. Much to my surprise, I found the document on the website of the Ford Library.

Brezhnev, Ford, Rodman, and Sukhodrev have all passed away, leaving me as the only participant. Had Trump not brought the issue of Russian interference in a presidential election to the fore, I would never have paid any attention to it. It would likely have remained buried forever in hundreds of thousands of pages of diplomatic and presidential records from that era.

President Trump and his entourage have steadfastly denied that Russia interfered with America’s election. But influencing American elections has been an objective of Russia for at least 42 years.

Ford never mentioned this little conversation, lasting less than two minutes, to anyone. Perhaps he took it as no more than an offhanded pleasantry by Brezhnev to wish him well in the coming election.

But Brezhnev likely intended more. Alexander Akaloskvy, who was our State Department interpreter, included a relevant note in his personal Helsinki CSCE record. Akalovsky was not with Brezhnev and Ford when they stepped out onto the porch. But as Brezhnev moved to his car, Akalovsky overheard him ask Sukhodrev if his remarks to the president might have been overheard by press correspondents standing nearby. Sukhodrev assured Brezhnev that in interpreting, he had deliberately lowered his voice so that only the president could hear him.

This further confirms that Brezhnev intended his comments to be more than mere pleasantry. Forty-two years ago, a Russian leader privately offered unlimited assistance to a presidential candidate. Given the continuity over the years of Russia’s covert-action methods, it is of little surprise to see Russia doing in 2016 what Brezhnev offered to do in 1975. The difference is that this time the offer was accepted, while in 1975 the United States was led by a man of great experience and absolute integrity, who ignored the offer.