Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

Like a lot of Millennials, Sarah Curley has some tattoos. The public-health educator, who lives in Madison, Wisconsin, has a bouquet of wildflowers and the Greek word sophrosyne (meaning “temperance”) on her right wrist; some song lyrics on her ribs; and the phases of the moon on her inner left forearm.

Then, there is the 3 on the back of her neck, which represents her and her two sisters. In college, she went into a tattoo shop in Eau Claire, wanting a simply crafted number. “The artist—his style was very vivid, very detailed, and kind of on the macabre side,” she told me. Still, he was the guy available that day and she was impatient. “He did a good job—I mean, it was beautifully done,” she told me. But the tattoo ended up “thicker and more ornate than I would have designed for myself.”

At any other point in human history, that would have been the end of the story. Tattoos were forever. But in the past 10 years or so, tattoo removal has gone from being an expensive procedure performed by a dermatologist to something you can get done on a walk-in basis at your local strip mall. The number of laser-removal procedures is surging. Members of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery zapped 63,000 tattoos in 2012 and 164,000 in 2019; even more tattoos have been removed by technicians at medspas and clinics.

Curley had three laser-removal sessions. “The tattoo is really, really faded,” she told me. “It has worked incredibly well.” Removal is a wonderful development for people like her, who find themselves feeling queasy about something embedded in their skin. (One removal technician told me she had scrubbed off half a dozen Deathly Hallows symbols after J. K. Rowling’s comments about trans women.) It is an even better development for people with tattoos that inhibit their employment prospects or remind them of a spell of incarceration or an abusive relationship, or that were inked during a mental-health crisis.

Yet it is also a profound shift for an art form and a cultural practice predicated on permanence. Tattoos might be decorative, an element of style. But they are not a haircut or an outfit. They are part of the body, intended to last a lifetime. If the ink can disappear, so, too, may the meaning.

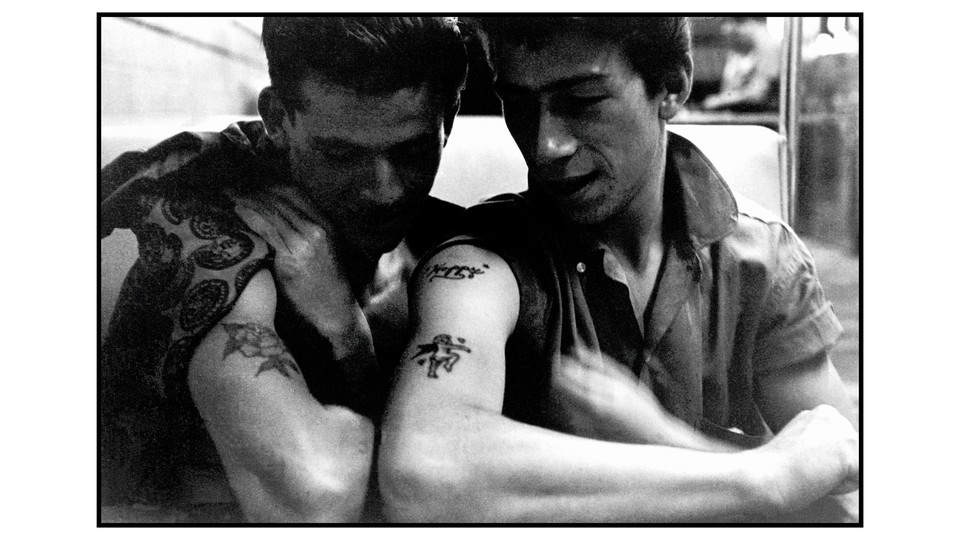

The oldest preserved tattoos belonged to a person today known as Ötzi, a resident of the Italian Alps some 5,300 years ago. The guy had 61 tattoos, including bracelets on his wrists and black dashes all over his body. Lars Krutak, an anthropologist who studies tattoos, told me that the cultural practice of tattooing almost certainly goes back further, developing independently in many places around the globe. For generations, the Māori people used miniature chisels to create stunning facial tattoos, a practice that has come roaring back in popularity in recent decades. One third-century Roman described the barbarians of Britain as “marked by local artists with various figures and images of animals,” the dye in their skin growing and changing along with their bodies.

In many communities, a tattoo was a sign of membership, achievement: A man might receive a tattoo after fighting in battle. The style and design tended to be dictated by a given community’s cultural practices, more than the aesthetic preferences of the recipient: You got the tattoo, not just your tattoo. “Almost invariably, these tattoos, these traditions, are connected to a mythic past, an ancestral past.” Krutak said he’d brought up removal with elders in several communities, including the Konyak Naga in India and the Kalinga in the Philippines. They would always respond, “I can’t even answer that question. We would never think to remove a tattoo.” Like: Why the hell would you do that?

Now one in three Americans has at least one tattoo. More than half of women in their 20s do. The practice has become common across racial, wealth, and educational divides: One in four people without a high-school degree has a tattoo, as does one in five people with a graduate degree. The stigma associated with them has faded, if imperfectly and unevenly; now most adults without tattoos say they don’t think any better or worse of a person for having one. Counterculture has become culture: riotously diverse, highly ornamental, prone to fads, an expression of autonomy and personal style.

As tattoos have surged in popularity, the capacity of technicians to remove them has grown too. Doctors have been using lasers for more than 50 years to remove tattoos, Tina Alster, a dermatologist and the founder of the Washington Institute of Dermatologic Laser Surgery, told me. The procedure works on a principle called “selective photothermolysis.” Different parts of the body absorb different amounts of energy from lasers pulsing at different wavelengths. Doctors find and use wavelengths that get absorbed by pigment but not tissue, breaking up the ink and allowing the immune system to remove it. (In other words, the laser helps a person pee out their tattoo.)

Over time, Alster told me, laser machines have gotten much more powerful and more precise. Doctors have become more proficient at identifying the best wavelengths and techniques for different inks and skin tones. The results are evident to everyone. I am old enough to remember Angelina Jolie removing a bicep tattoo of a dragon with Billy Bob Thornton’s name over it back in the early aughts; the image blotched and faded and looked (frankly) terrible before it got light enough for her to cover it with makeup for the red carpet. (“I’ll never be stupid enough to have a man’s name tattooed on me again,” she said at the time.) Now celebrities get ink scrubbed off with stellar results and little fanfare. How many tattoos does Pete Davidson have? How many has he gotten zapped off? Nobody knows.

That said, laser tattoo removal is not magic. It requires multiple treatments, sometimes as many as 10 or 12, spaced weeks or months apart. It hurts, much more than getting a tattoo in the first place—like sizzling oil on the skin. You can sometimes still see smudges and shadows after the removal process is done. But it works well enough that hundreds of businesses now offer the procedure to thousands of customers. (It is more lucrative to remove tattoos than to ink them.)

This is changing the practice and culture of tattooing itself. Perhaps the most tangible and immediate result, tattoo artists said, is that cover-ups—turning an ex’s name into a flower, or a flower into an all-black sleeve, for instance—have become less common. Now people are much more likely to get a tattoo lasered off.

They’re more likely to get different kinds of tattoos in the first place too. Fine-line tattoos and ones with tiny, pointillistic-dot work, for instance, have become trendy in the past decade. Such tattoos tend to fade and blur more and faster than tattoos with heavy, emphatic lines. Several artists I spoke with mentioned that young clients, in particular, seemed to be okay with that; many were planning to change up their artwork in the future anyway.

Indeed, the attitude of young customers is the thing that has changed the most: Gen Zers just don’t understand tattoos as permanent in the way that Gen Xers do. They might get that removal is difficult and painful and imperfect. But they also get that it’s an option.

I had expected the tattoo artists I spoke with to be annoyed or even offended by these shifts. I found many of them sanguine. People’s bodies are their own; plenty of tattoo artists know a thing or two about getting impulsive tattoos (and getting them removed). And the advent of laser tattoo removal seems to be making tattoos more popular, not less. “For me, it’s really important to create something that will be organic and natural and beautiful in 20 years,” Sasha Masiuk, who owns an eponymous tattoo studio in Los Angeles, told me. “But no, I am not upset if someone wants it removed.”

Permanent never necessarily meant serious, after all. Sure, people get tattoos to commemorate their mother, recall a near-death experience, create art with their body, or become part of a criminal organization. They also get them because panthers are sick, because the date went great or horribly, because we’re here on this little planet and we’re all going to die someday so why not? “One school of thought is you wait and you wait and you wait and you find exactly the right artist and you pick exactly the part of the body and you wait and you wait,” Kip Fulbeck, an art professor at UC Santa Barbara and an expert on Japanese tattooing, told me. “Another is: It’s your body. You get what you want when you want it. If you hate it, maybe it’s just a map of your life.”

Plus, even the most permanent tattoo won’t last forever. “It’s a very strange art form,” Fulbeck said. “If I make an installation or I create a book, there’s documentation. It’s there. For a tattoo artist, you make your masterpiece, and then it goes outside or goes to a tanning booth—or goes and gets hit by a bus.”