Meet George Jetson

After 50 years, is Paul Moller’s quest to create the world’s first flying car about to come true? Someone may be betting nearly $500 million that it will.

It’s round, of course, and painted a shiny Reagan-era blue. Eight circular rotary engines ring

the fiberglass body, and if they were still working, they would blast it straight up off the ground with a buzzing noise like a locust invasion. In the plastic-bubble-covered cockpit, there’s a bank of metal toggle switches and a seat made of gray pleather. The M200X, as it’s called, rests on dainty tires about 10 feet from Moller’s “Skycar,” a more recent take on this eccentric engineer’s lifelong compulsion to create cars that fly.

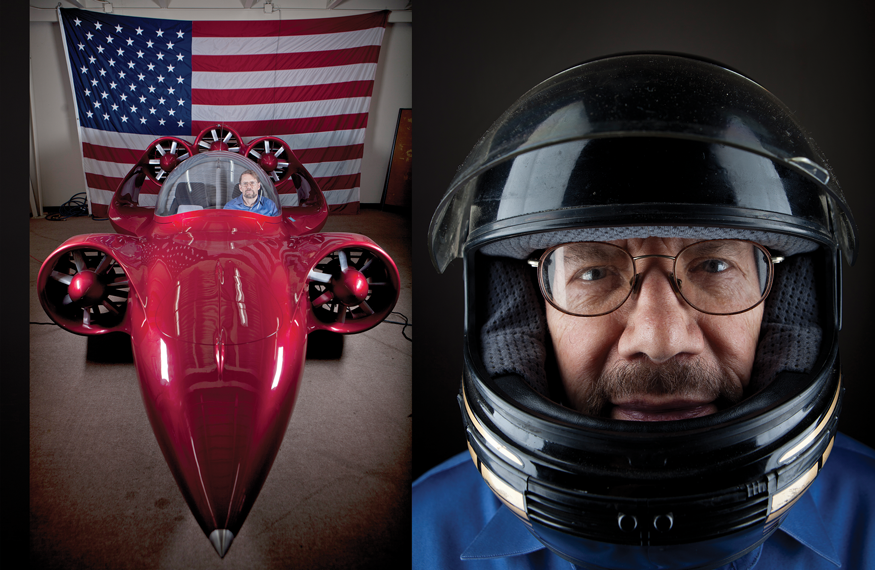

The Skycar is cherry red and resembles a mash-up between Luke Skywalker’s Landspeeder and X-wing fighter. It’s a three-wheeled contraption, also with a bubble cockpit, a pointed nose like a missile and a joystick control that looks like it was salvaged from an old Atari. Nevertheless, it’s sexy and sleek, like something that sprang from a comic book, designed to be piloted by a square-jawed superhero on urgent business. Pop open its hatch door, slip onto the velour bucket seats and let the adventures begin.

Moller, a former UC Davis aeronautical and mechanical engineering professor with cautious blue eyes, a well-trimmed Van Dyke beard and a deeply embedded thrill-seeking streak, has flown both of these revolutionary vehicles—in the field behind this building, at the UC Davis airport and on his almond farm in Dixon. He says it feels like being on a magic carpet.

Someday soon, he hopes you’ll be piloting one, too. He has a dream where they roll off the assembly line and into the hands of consumers, like Toyotas or the BMW 540i he currently drives.

No, he’s not crazy. Just short on cash.

An M200X test flight

It turns out that making an aircraft that flies both vertically and horizontally (a VTOL, or vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, as it’s known in aviation circles) is expensive. Very expensive. Even though Moller has invested more than $10 million of his own cash over the years, he says that money is the only thing holding him back from mass-producing working Skycars.

“I’m out grubbing for money everywhere rather than doing the technical things,” says the 76-year-old, sounding frustrated, weary and a bit disillusioned. “Money, it’s always money.”

He has hustled and bumped through five decades of research, dumping every dime he could scrounge—more than $100 million, he estimates—into this flight of fantasy. Currently, he doesn’t even have funds to keep his prototypes in the air, and says it would cost $5 million just to get his venture restarted.

But his fortunes, both literally and figuratively, may be about to change.

Recently, Moller was offered nearly a half a billion dollars to start up production once again. A consortium of investors headed by a Chinese-American businessman and art collector named John Gong, who also harbors a personal passion for flying, has entered into a Memorandum of Understanding with Moller for an initial imprest of $80 million and a total investment of $480 million, including a Chinese plant to produce the flying cars.

If that money comes through, it may be Moller’s last chance for a triumphant final voyage on his lifelong mission. He says his cars could be flying in less than two years in the air over Harbin, an inland port city of over 10 million in Northeast China where his investors want to build a factory. Gong, who discovered Moller’s company on the Internet and recently visited him in Davis, hopes it could be sooner and is working hard to get the necessary approvals from 46 different departments of the Chinese government in the next few months.

“If you look at the humble building, you will say, ‘My God, he probably only can do a bicycle type of deal,” admits Gong of Moller’s current space. But, he adds, “I looked at the design and I looked at the drawing and I looked at the machine he currently has, then I believed him. The deal is going forward.”

* * * *

For more than 50 years, Moller has worked ceaselessly to build the world’s first commercially produced, consumer-oriented flying car for the masses. One that could rise up out of your driveway, zip over terrain and traffic jams at speeds up to 400 miles per hour (though 200 mph will likely be cruising speed), and transport the average Joe with the same nonchalance as an earth-bound car does today, like George Jetson heading off to make sprockets in the morning.

Moller says that Skycars would function on new, three-dimensional highways in the air, be safely controlled by computers, but also still able to drive down the street on their wheels to the grocery store when necessary. Unlike helicopters and airplanes, which are expensive to maintain and difficult to operate, anyone could handle a Skycar with its simple computerized controls. Think of Bruce Willis piloting his air taxi in The Fifth Element, or Harrison Ford’s “spinner” in Blade Runner. Sound crazy? Just in April, The Wall Street Journal opined that, “by 2025, fully autonomous vehicles might hit the streets in meaningful numbers.” The only difference is, Moller believes they will be floating above the streets instead.

An M200X test flight

“I’ve always had this personal desire to build something that you and I could fly in,” he says of his relentless pursuit, sounding like a 21st-century Henry Ford. “Something practical.”

Working out of his garage at first, and later a low-rise faded facility with retro diagonal wood planks for siding in a research park just off I-80, Moller has built (and flown) a half dozen of these volantors, as he generically calls them, over the years. Yes, they all actually can fly. One saucer has been in the air more than 200 times. The vehicles have earned him investors and worldwide attention—including a spot in Esquire’s 2003 “Genius Issue,” a 2005 profile on 60 Minutes, and the covers of Popular Science, Popular Mechanics, Forbes FYI and The Los Angeles Times Magazine.

They’ve also won him professional admiration and respect.

Dennis Bushnell, the chief scientist of the NASA Langley Research Center who has followed Moller’s work, says he considers him to be an “early pioneer,” in this new field of aviation, and an “experienced, talented and inventive engineer.”

“He’s regarded very highly [by the scientific community],” adds Case van Dam, Chair of UC Davis’ Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering. “[Aeronautics] people really like his ideas. The whole idea of a small vehicle that can take off and land vertically is very viable, and I think Paul’s work and other people’s work shows that.”

Despite that acclaim, commercial success has been elusive. He’s weathered a handful of flawed prototypes, millions of dollars of profits and losses from side businesses (including an innovative engine and an iconic motorcycle muffler), accusations of scams and three marriages. Not to mention that his goal of a world with Skycars is as much a futuristic daydream today as it was when he began. The Skycar has never flown very high (25 feet), or stayed up very long (a couple minutes).

But Moller’s aspiration has remained shockingly stable despite the obstacles. In fact, if there is one major success in this entrepreneur’s history, it’s his optimistic ability to hold steady on his vision despite time and circumstance. He believes.

It’s a single-minded tenacity that is the mark of either genius or madness, deciphered only in hindsight. Success would make him a genius, failure relegates him to a minor scientific footnote. Moller’s fate still hangs in the balance. Will he be remembered as a visionary who ushered in the future of consumer travel? Or forgotten for cruising into the back alleys of reality?

* * * *

Moller was a 20-year-old engineering prodigy working on a secret missile design for the Canadian government when he had his first close encounter with a flying saucer in 1957.

It didn’t come from outer space. The one he came across was man-made, cobbled together with riveted aluminum, giant fan engines and a heavy dose of Cold War paranoia. A classified, disc-shaped military vehicle dubbed Project 1794 that could take off straight up into the sky without the need for a runway, it was meant to provide a way to launch an airborne counterattack against the Soviet Union if the communists should destroy our airfields with a nuclear first strike.

Although Moller was not directly involved (he was just a summer hire working with the Canadian Defense Research Board, which shared a facility with Avro, the company developing the top-secret program for the U.S. military), he wanted to know more. He had been introduced to the then new idea of circular flying objects by the writing of Donald Keyhoe, a former Marine Corps major and pulp author who penned a widely read article for True, a popular men’s magazine, called “Flying Saucers are Real,” which spawned a series of books on UFOs.

“I had a security clearance, so I got to see and learn a lot about that particular project,” says Moller, who didn’t get near the vehicle but studied design documents for it.

He was fascinated by the idea of flying like that—rising vertically to hover and dart at will. He discovered that unlike airplanes that relied on wings to maneuver, or helicopters that needed the power of a giant rotor to lift off, this sleek craft seemed to be able to shoot up using only ducted fans. Its designers were making innovative use of the Coanda effect, a principle of aerodynamics that shows that an airstream can stick to a rounded object and flow around it in a way that pushes it up into the air, which is why we have flying saucers instead of flying boxes. It was a revolutionary leap in aerospace technology, and one that changed Moller’s life forever.

* * * *

On a warm March morning, UC Davis students are riding bikes and walking on the winding street outside of Moller International’s headquarters. But inside, it’s hushed and dim with the cool feel of air undisturbed by too much motion. The carpet is a worn industrial brown and fat strips of dark mauve paint are the only pops of color in the bland space. Walking down the narrow passage that connects the front offices to the fabrication plant tucked behind two thick swinging doors, Moller, his receding reddish brown hair swept to the side of a tan forehead, stops to point to one of dozens of photos pinned to a board on the wall. It’s a self-referential hall of fame, or maybe a morale booster before hitting the deserted shop in the back—currently, he and his general manager Bruce Calkins are the only two people there, and neither gets paid in any reliable fashion.

Moller patiently points out highlights on the display, something he’s done for reporters dozens of times over the years. It’s a long history, and sometimes he has trouble remembering the exact dates. Here he is surrounded by press after a test flight in the ’60s. There he is in a ’70s shot sporting checkered pants and a striped shirt, hair shaggy and disheveled, holding a muffler he invented. “That’s the car I built when I was 15,” he says, pointing to a crinkled black-and-white photo of a Deco-looking auto at nearly 12 feet long, with a door that pops up DeLorean-style. A teenage Moller is smiling roguishly from the driver’s seat. “I built every piece of metal on there.”

A Ferris wheel made by Moller at age 11

* * * *

Paul Sandner Moller was born and raised in rural British Columbia, Canada in 1936, where he lived the cliché of walking a mile to school in the snow. His dad, a Dane, was a chicken farmer. His stay-at-home mom had an unconventional intellectual bent despite a lack of formal education, filling the house with classical music and avant-garde ideas like reincarnation.

It was clear early on that Paul, their oldest child and only son (he had three sisters, two have passed away), had some interesting abilities and the drive to realize his daydreams. At 6 years old, he began building a one-room house behind his parents’ home. At 8, he built another one. This time it had two rooms, a peaked roof and stood for 50 years, his dad using it for storage. “I’d always been really in love with mechanical things,” he says of his talent for wielding tools of any sort and his obsession with understanding how things are put together. “It just came so naturally to me.”

Just as intrinsic to his personality was his fascination with flying. Once, he found a pair of hummingbirds trapped inside a building. Exhausted from trying to escape, they were slow enough that he was able to catch one in his hand and release it outside.

“All I remember is holding it and just opening my hand up,” recalls Moller. “It was inspiring to see the level of mobility that it had to hover right in front of your face for maybe a fraction of a second and then accelerate so rapidly despite being tired. It just disappeared.”

From that moment on, the idea of harnessing the speed and power to blast off into the ozone, then levitate and linger at will held a firm place in his imagination. But it didn’t stop him from creating more earthbound objects.

At 10, he built a working, three-wheeled car. With winter weather making it impossible to tinker outside, Moller took over the living room of his parents’ tiny, 500-square-foot house with their blessing. “I didn’t have drill [bits],” he recalls, the stretched vowels of a Canadian accent slipping into his speech. “So when I’d have to drill a hole, I would take a metal rod and put it in the fire, get it red hot and burn the holes through the wood. This would create smoke, of course, and there was sawdust. The only condition was that if they had company, I had to move it.”

When spring and summer came, his projects moved outside and grew even bigger. “The next thing I built was a Ferris wheel,” he says. “In between, I started a snowmobile. Before I got very far on that, I decided to build a helicopter.”

It sounds like hyperbole, but Moller actually did build these and more. The Ferris wheel was a wood-framed structure with four arms that shunted lucky neighborhood riders 20 feet into the air via a hand crank. Framed near his desk is a hand-drawn design of the helicopter, done as a teenager, when the aircrafts were gaining popularity in the Korean War. He never had the equipment to make it fly, but he got the tail rotor working, and his dad later hooked it up to a battery-driven motor to keep the air circulating around his chicken eggs.

But despite that obvious brilliance when it came to designing and building, Moller was a poor student, inattentive and easily distracted by his own thoughts. Rather than college, he ended up at a three-year technical trade school in Calgary, where he became a “quasi-engineer,” landed that summer job where he learned about the military flying disc, and later worked at Canadair designing anti-icing machines. But his intellectual curiosity was far from fulfilled, and he decided to enroll for fun in upper-level classes at nearby McGill University, which was home to one of Canada’s premier engineering programs.

“I wanted to see how stupid I was or smart, depending on which way you look at it,” he says. “I decided to go and see if I could take the toughest course in graduate school in an area I knew absolutely nothing about.” That ended up being a night class in applied mathematics, which he passed. “The next year I decided, ‘What could I take that would be even worse than that?’ ” So he signed up for chemical engineering and supersonic fluid flow.

While there, he met Dr. Barry Newman by chance one night as the renowned aeronautics professor was returning from a Princeton Symposium on “ground effect machines,” or flying saucers in layman’s terms. Moller had been experimenting with how air could lift objects by creating a reverse tornado in his apartment and attempting to build scale aircraft models using the Coanda effect.

A car he built at age 15.

“It was just one of those coincidental things. I’d say destiny,” says Moller, describing Newman as the third most important person in his life after his parents. Newman was so impressed with Moller that he helped him enter McGill as a graduate student, bypassing his entire undergraduate career.

“Paul was extremely intense,” says Daniel Guitton, another of Newman’s graduate students who became a close friend and roommate of Moller. “When he got into a problem, he just never let go. He’s an extremely hard-working person who would work basically day and night. Even when he was sleeping, he’d give the impression he was thinking.”

Moller and Guitton did find time for fun, though, racing go-karts for a few seasons at speeds up to 100 miles per hour, usually with no helmets and only leather jackets for protection. Moller was so good, and such a “daredevil,” says Guitton, that he was sponsored by a kart manufacturer. “He was not afraid. He’d really go all out. It was quite dangerous.”

But it was in the lab that Moller found the most satisfaction. “It was like heaven,” he says of his time at McGill. In addition to earning his master’s and PhD in three years, Moller met Jeanne Cejka, a 6-foot-tall physiological psychology student who shared a Russian class with him, and the two married on New Year’s Eve when Moller was 26 and she was 23.

After Moller received his doctorate, it was Jeanne who, tired of the cold, encouraged him to look for work in a warmer climate. As it happened, UC Davis was staffing up its nascent mechanical engineering department at the time. The day the Mollers visited in August 1963 for his interview, it was 112 degrees, with the sun burning her skin like “direct radiation,” she recalls. He got the job, and they moved to a house on B Street on the edge of town, which Moller chose for the workspace its large garage provided.

* * * *

By next summer, when he was 27, Moller was building his first flying saucer, based on the design of Project 1794. Along with his friend Daniel Guitton, who came down to help, he was sequestered in his garage, constructing a 14-foot primary blue disc with white trim and three small wheels. “He was like a one-man aircraft factory,” recalls Guitton. “He would just go all out for days and days and weeks and weeks. He could weld all the parts, even weld the aluminum, which is not easy.”

“Oh my God, that was fun,” says Moller with a mischievous laugh, adding that he got a 50-pound bag of peaches so that they wouldn’t have to stop working to eat.

But, after welding together about 1,250 tiny steel tubes to make a “spider web frame,” that project went from imagination to reality. Moller had taken his first giant step and finished his futuristic vision of transportation.

The craft did indeed fly in the spring of 1965 at the university airport, hovering two feet off the ground before losing stability and beginning to wobble like a quarter bouncing on a hard surface. Not quite the high-altitude darting of his reveries, but enough to keep his rose-colored glasses firmly in place. He immediately began refining the concept. His flying saucer dream seemed closer than ever to fruition, but on the personal front, his marriage was in trouble.

Jeanne, who was commuting to Berkeley to finish her own PhD, was having an affair. Often, Moller’s focus on his work left little attention for her, and sometimes his temper could be explosive. “His reaction when he was angry was to yell, that’s all,” she says. “I just noticed that I needed something more in a relationship.”

She left in 1966. But “when the soreness of our split began to fade, then we were just friendly again,” she says of Moller. “Because I do love him. I am indeed one of his biggest fans, as I always have been.”

Left on his own, Moller dove even deeper into his work. By April of 1967, he had refined his saucer and it was ready for its close-up. He set up a media event and took off once again from the UC Davis airport, this time wobbling unsteadily four feet in the air for nearly three minutes in front of an excited crowd of journalists, college students and emergency personnel before being forced to land by a blown hose.

“That’s when we got worldwide coverage,” he says. “It was exciting for those who were watching it, but less exciting at that point for us because I already knew that the vehicle was not a practical vehicle. It was very, very delicate. I’d already started the second one.”

* * * *

Moller’s personal life was also taking off. He began dating an English major with long brunette hair and a wide, welcoming smile named Vicki Schlechter—even asking her to pose in a space outfit in a saucer at the 1967 California State Fair. “She was a very mature 22-year-old. I met her and it just took off from there,” he says.

On the production front, he finished the new XM-3 in 1968, powered by a ring-shaped fan encircling the cockpit. It was crafted out of material from a used rocket, made by aerospace giant Lockheed. Moller had a friend who worked there, and through the contact managed not only to get his hands on the leftover high-tech material, but also to have the circular ring machined by the company. But it was a short-lived innovation that he flew only a few times because it lacked maneuverability. He moved forward to the next design and soon found his first investor, a businessman named Bernardo Majalca who attended the 1967 test flight, willing to help him start his own company called M Research for both of their last names. Despite having tenure, Moller scaled back his university job with Majalca’s urging in order to focus on the business (Moller would eventually leave UC Davis completely in 1975 after 12 years at the school). He also purchased a decrepit, 28-acre almond ranch on Putah Creek in Dixon and began replanting the orchard, indulging in a passion for working on the land (eventually, he even sold organic almond butter on eBay).

But Moller says Majalca nearly went bankrupt only four months into their venture, leaving Moller unable to pay his four employees. Undaunted, he renamed the company Discojet in 1971 (a moniker he dropped a decade later because people “kept getting confused between Discojet and discotheque,” he says) and began to think of ways to make his own money to fund the business. Moller had come up with a number of innovative machines while developing the Skycar, and wondered if maybe they had viable commercial applications. First, he thought of taking a lightweight engine and strapping it onto the back of skiers, jet-pack style, to help them up hills without lifts. But the common-sense safety issues led him to abandon that plan.

Instead, he focused on a muffler for motorcycles, ATVs and boats that both damped noise—a budding environmental concern—and increased power by using a series of discs to change the exhaust airflow, and founded a company to build them in 1972. Moller had long ridden—and raced—motorcycles and dirt bikes and had a love of the sport. The new muffler, dubbed the SuperTrapp, quickly became the most popular after-market accessory for bikers and an iconic brand that is still used today by top racers. SuperTrapp had about $100 million in sales between 1972 and 1988, when Moller sold the company for $3.5 million. He also got involved in real estate and developed the Davis Research Park—where he also built his own facility—in 1980, earning more than $4 million when he sold it over the next few years.

All of it went straight back into his flying saucers. And it appeared to pay off when he discovered the German-engineered Wankel rotary engine which worked without pistons. The engine provided the light weight and power that Moller had been searching for, and adding it to his M200X flying saucer design filled in a key piece of missing technology. He acquired the rights to the engine in 1985 and spun it into another company called Freedom Motors. The M200X saucer (the X stands for experimental) evolved into the Jetsons-like craft with eight engines around the edges and a bubble-domed cockpit at the center.

Moller’s work was advancing quickly.

But, like George Jetson, Moller now had a young family, too. In 1974, his son Jason was born, followed a couple years later by his daughter Jennifer. And despite his drive and the “relentless pursuit” of his flying machines, says daughter Jennifer, who lives in Sacramento, Moller found time for his family: “He’s just absolutely a wonderful father. He was so involved with us. I would go through phases where I would be interested in something and I’d be almost obsessed with it. Say it was badminton and I wanted to play it every night, and so every night I came home, he’d play badminton with me for hours.”

Jennifer Moller says that her dad created a free, anything-goes environment on his farm much like his own upbringing. It wasn’t until her 20s that she realized her dad “has very little sense of safety,” Jennifer recalls. “While we were growing up, we were on motorcycle bikes all the time, no helmets. We were jumping off the house onto the trampoline.”

She recalls when she was about 4 that her dad loaded her 6-year-old brother on the back of his bike, put her on the front and went off-roading. They hit an eight-foot-deep ditch hidden by tall weeds.

“You hit a ditch like that and the motorcycle just stops dead, instantaneously,” says Moller. “My daughter flew over my bar and my son flew over my head.”

The kids weren’t hurt, but Moller broke vertebrae in his neck. Miles from nowhere, he had to ride back for help.

“I didn’t dare call Vicki,” he says. “She delivered me to the hospital at least three or four times with accidents, which didn’t help our relationship too much.”

He called a neighbor instead, but Jennifer says Vicki started “planning and preparing for something to happen. It was almost like, ‘Well, okay. There he goes again. I can’t control him. I can’t stop him, so I’ll just be as prepared as possible for when disaster strikes.’ ”

* * * *

In May of 1989, Paul Moller, then 52, had his most successful test flight ever, but one that could have been his last.

It was the day of his third wedding anniversary to his third wife, Rosa, (he and Vicki divorced in 1985). Wearing a blue fireproof suit, he kissed her, then hopped into the newly revamped M200X, using its joystick control to raise the craft to 60 feet above the Davis factory—the highest public flight to date—for a little more than two minutes while a crowd of international press once again snapped pictures and filmed below him.

Jennifer, there with Vicki, remembers thinking, “Wow, this is great. This is a perfect flight.”

Paul Moller at Moller International headquarters in Davis.

But Moller knew different. This was not the flying car that was going to be in every American driveway. This craft had engineering problems—the blades of its engines, rotating at near-supersonic speeds, had the tendency to break off mid-flight, as Moller had learned in ground tests when one flew off just a foot away from the head of an employee. They could whip free like deadly metal missiles in unpredictable directions—toward the pilot, maybe, or those reporters and family on the ground. But Moller wanted the flight for authenticity reasons—he needed more money to get to the next level and had to prove to investors and critics that he was on a viable track.

“I was not comfortable during the flight but it was a credibility issue. I really needed to fly it,” he says. “I remember I did a two-minute flight and then I turned around, and as I was going back to land I said to myself, ‘I’m going to live.’ Because in the back of my mind I knew that the fan blade could go at any time. It was a moment that I won’t forget. It was worth the flight, but I didn’t want to ever do that again, not with that kind of risk.”

The crowd was impressed, and Moller was on a roll. Over the next decade, he received military and government contracts for an unmanned flying robot called the Aerobot that he created from the same technology. Caltrans purchased them to examine bridges. Cash was flowing, he says, and he leapfrogged past the M200 technology to begin on the Skycar.

“I was raising a lot of money at the time very easily,” he recalls, standing in front of a display case of miniature replicas of his crafts. Inside each is a tableau of plastic dolls—some of the men in tuxedos, a few of the women in sparkly dresses fashionable in the Discojet days. “I’m always believing that I’m going to be able to do the next phase, and if the funds aren’t there, you end up shortchanging the phase you are in.” Moller began taking preorders for the Skycar, relegating the M200 to a service vehicle to be used for crop spraying or other workhorse tasks. Investors poured millions in, many wealthy patrons from foreign countries like Oman, but also more family and friends. Over the years, Jeanne invested $76,000 in the Skycar.

Along with the money came good press coverage from outlets as diverse as People Magazine and The New York Times. The King of Pop even called in the early ’90s to inquire about purchasing a Skycar for himself. Moller was walking through the factory with a reporter from The Economist when “over the loudspeaker comes, ‘Michael Jackson’s on the telephone,’ ” he recalls. “It’s sort of funny because he has that squeaky voice.” But despite Jackson’s interest, Moller said he never seriously considered selling one to him. “We just played along with it, but we didn’t push it seriously,” he says. “The worst conceivable thing we could imagine at the height of his popularity was to have Michael Jackson killed in one of our Skycars.”

* * * *

When Moller finally had a serious crash, it wasn’t the Skycar that went down. It was his reputation. Moller had been selling stock privately through the Internet and other avenues since at least 1997 and raised $5.1 million from more than 500 investors, according the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In 2001, the company registered with the SEC to sell stock. In 2002, its stock began trading over the counter and reached more than $5 a share. That year, he also piloted the first successful public test flight of the Skycar at a stockholders meeting in Davis. But in 2003, Federal regulators accused Moller of making false and misleading statements to his private investors about the Skycar and the value of patents held by the company, and of including some of that information in the company’s paperwork to the SEC. Moller eventually settled the SEC’s civil suit by paying a $50,000 fine without admitting to any wrongdoing.

“If you see some of the stuff on the Internet because of the SEC thing, you might believe I’m a crook,” he says. “I know better than that. I think most people that know me know better than that.”

But the damage was done–popular trust in Moller and his invention evaporated overnight. Internet searches on his company turned up charges of fraud rather than successful flights, a problem that still dogs him today.

“Some people say it’s a scam. I don’t think it’s a scam,” says Clark S. Lindsey—who has followed the Skycar saga for years while editing a science website called hobbyspace.com—of the charges. “I think he’s sacrificed his life for this. If it’s a scam, it’s on himself.”

Moller’s newest potential investor John Gong agrees. “He is a good guy. He is a scholar and a gentleman,” he says. “He is honest.”

But the stock price tanked, trading today at 20 to 30 cents a share. It became impossible to raise the money he needed, and despite retaining core supporters, the incident has been hard to shake.

“It’s like the sheriff coming into your house and asking your husband how long he’s been beating you,” says Bruce Calkins, Moller International’s general manager who helped take it public. “The accusation itself is so weighty, so onerous that you can’t get rid of it. Once it’s been said, once it’s been published, there’s nothing you can do to convince people that there isn’t something behind it.”

If Moller can be faulted for anything, he says, it’s his unwavering enthusiasm. Whether it’s racing go-karts or creating the Skycar, Moller is certain he can do it and isn’t shy about saying it. But Moller’s own convictions may have been his undoing. The SEC “thought he was making false promises, but he was merely being optimistic and trying to describe the dream and where he thinks he could go,” says his ex-wife Jeanne LaTorre. “He’s no flim-flam man.”

“He always forgets to emphasize the ‘Oh, by the way, I can do this tomorrow if I have the money,’ ” when speaking to investors or the media, adds Calkins. “He forgets the ‘if I have the money’ [part]. It’s a persistent problem. You’ve got to have money in your hand before you can tell someone a schedule.”

For Moller’s part, he says that the past 10 years since the SEC action have been the toughest he’s faced. “I’ve been in my Job period since 2002,” he says, strain creeping into his voice as he refers to the biblical story of a righteous man whose faith is tested by adversity. “I can promise you it’s been the biggest struggle of my life just keeping things together with this extended period of inactivity.”

Instead of testing new technologies, he spends most days in his cluttered office. The walls are covered with renderings and photographs of test flights. Notably, his desk is missing a computer. He doesn’t use one, nor does he use e-mail. Any e-mails sent to his office are printed and handed to him. He doesn’t use a cell phone either, except for when he travels. Instead, he simply has several calculators and a landline phone on his desk.

But he adds that spending less time on the Skycar has helped him delve deeper into other pursuits like alternative health. Reference books and journals from around the world line his shelves. Every day, he takes more than 75 pills to improve his health and extend his life, including ribonucleic acid (RNA) supplements and a self-created allergy remedy that combines vitamin C, bioflavonoids and pantothenic acid. If looks are any proof, his research has paid off—he’s easily mistaken for a man in his 50s and Jennifer Moller jokes that he is “reverse aging” like some sort of pill-popping Dorian Gray. He even had a racquetball court built into his headquarters and plays regularly. He matter-of-factly says that he “certainly” expects to live past 100, adding, “I would probably be happy with 130.”

He’s also embraced a new-age side and considers American spiritualist Edgar Cayce to be his “guru.” He even has a paper cutout of the lost continent of Atlantis (which Cayce taught about) tacked just off the coast of Florida on a world map on his wall.

“I’ve filled out my spiritual vision of where I’ve been, where I’m going,” he says of how he has spent his time these past few years. “I don’t know if the end product of my life is going to be my technology.”

* * * *

While the last decade has been slow for Moller, it’s been an era of rapid development for vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) aircraft overall. If nothing else, it has moved Moller closer to the success of building a respected legacy if not a workable Skycar—a man no crazier than the Wright brothers must have seemed jumping off sand dunes in their gliders at Kitty Hawk. It’s too soon to tell if he will be considered a pioneer, as NASA’s Bushnell suggests. But it’s pretty clear that the technology now exists for mass-produced VTOLs, with more companies entering this race with their own fantastical flying contraptions.

There is the Israel-based UrbanAero, which is developing the X-Hawk vehicle that carries 11 people. The Dutch PAL-V flying car completed a maiden voyage last year. Its CEO Robert Dingemanse isn’t shy about billing it as the “first viable flying car ever,” and expects to deliver it in 2015. Here in the U.S., Massachusetts-based Terrafugia took its “roadable aircraft” to air shows in 2012 and says it has more than 100 preorders for the $279,000 vehicle.

“This type of vehicle, whether you call it a flying car or a roadable aircraft, whether it’s Moller’s or other types, there has never been a commercial success. It just hasn’t happened, so people are skeptical,” says Terrafugia executive Richard Gersh. “If this were easy, someone would have done it, so clearly it’s not easy.”

But John Gong, who holds a master’s degree in electrical engineering and computer science from George Mason University, says Moller’s technology is the best he’s seen, and the design with the widest potential for consumer use. He also knows that time is running out for Moller—supplements can’t keep him alive forever.

“I see the urgency to either make this one go big or stay the size it is for a long, long time,” says Gong.

NASA’s Bushnell adds that the necessary highway-in-the-sky system is finally in the works. The FAA has loosened its rules for lightweight crafts like Moller’s and it is implementing an update and expansion of its aging air traffic control system that would allow for managing more types and quantities of flying vehicles.

Computer systems that can drive a car without human help—like the Google car—already exist, with technology that translates to the sky. In other countries, like China, which lack roads in many rural areas, the Skycar might be a plausible alternative to building roads—the same way some developing countries skipped landline telephones and went straight to cells. Even in bustling Chinese cities, congestion and overcrowding are making road travel difficult. In 2010, a traffic jam on a major highway near Beijing lasted 10 days, with some drivers moving only a half-mile each day. That makes a Skycar sound pretty good. Any VTOL will most certainly be for military and emergency use at first, and be costly, but, as Gong points out, “there are millionaires and billionaires, and they always want to have something that can take off from the backyard.”

Gong says he shares Moller’s vision of a mass produced Skycar. If the money comes through, Moller says the investment group anticipates production of 80,000 Skycars by 2016. He’s looking forward to test-piloting the next model, a 600 horsepower two-seater with wings that fold and a maximum speed of about 330 miles per hour in the air. Gong, who hopes to see one parked in his own backyard as a replacement for the helicopter his wife won’t allow, says he’s “positive” that the deal will happen: “We’re going to make the dream come true.”

Whether it does or not, though, quitting certainly won’t be an option for Moller, especially since he hopes to have another 50-plus years to fill.

“What does stop mean?” he asks. “I don’t know what I’d do if I stopped.”