The Great Famine (1845-1852) was a truly modern famine and one of the greatest social disasters in nineteenth-century Europe. Over a million people perished and a further million and a quarter fled the country which, by the Act of Union in 1801, was an integral part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the largest empire in history.

While power and wealth were vested in a small landholding elite in Ireland, subsistence was the lot of the three million landless labourers and cottiers whose lives were intimately linked to the cultivation of the potato and a specific variety, the Lumper.

The Lumper potato, a staple of pre-Famine Ireland

Many visitors to Ireland on the eve of the Famine commented on the levels of poverty they observed in the Irish countryside. Some, like Asenath Nicholson, believed that Ireland was teetering on the edge of a great calamity such was the extremes of poverty that she witnessed.

In the decades prior to the arrival of the blight there had been localised famine conditions in Ireland, but nothing compared to the Great Famine that was marked by both its absolute scale and longevity.

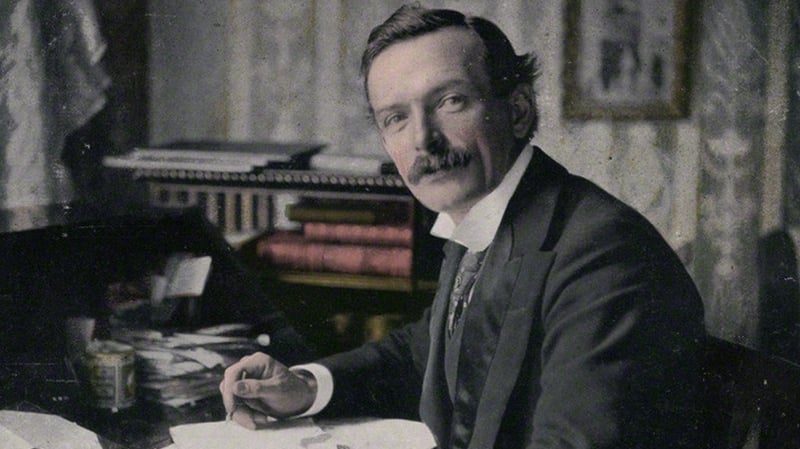

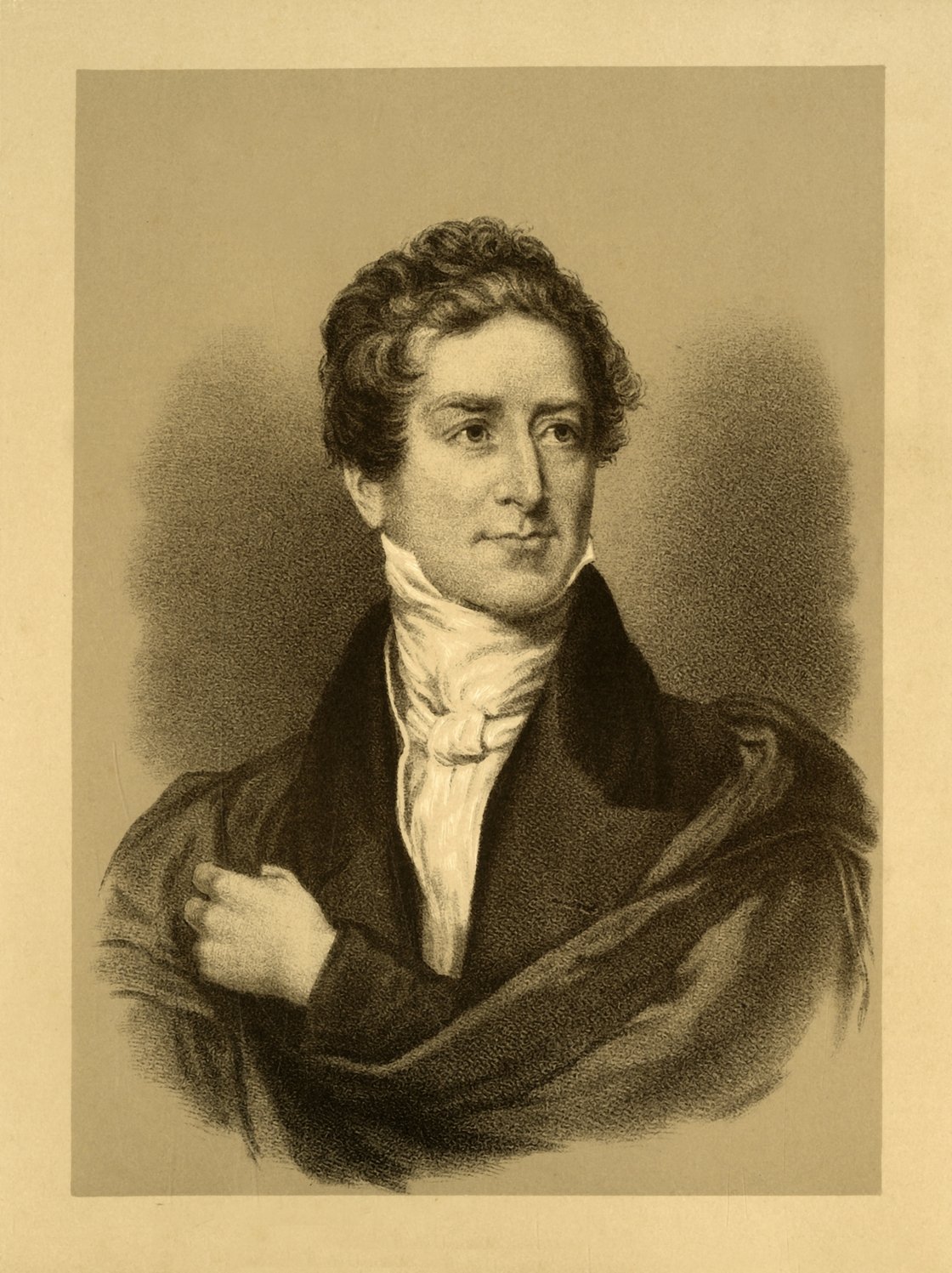

The arrival of the blight in Europe led to a partial failure of the crop in Ireland in 1845. A Tory government under Sir Robert Peel introduced a series of relief measures including the importation of Indian corn, the setting up of hundreds of relief committees in addition to the establishment of public works where people could earn money to buy food. The almost total failure of the crop the following year presented a different challenge to a new Liberal government under its Prime Minister Lord John Russell.

Sir Robert Peel, Prime Minister in 1845. Portrait by Thomas Lawrence. (Source: The Print Collector via Getty Images)

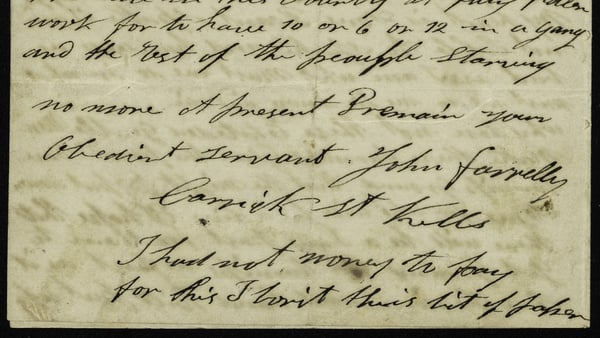

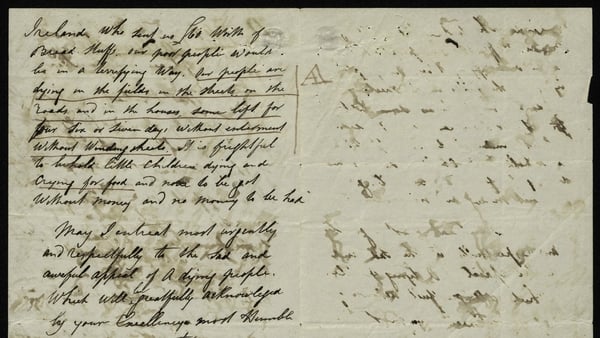

Public works became the principal vehicle of relief under Russell's government with Charles Trevelyan Assistant-Secretary to the Treasury directing Famine relief measures. Fr John McHugh, PP Tubbercurry, Co. Mayo wrote to the Lord Lieutenant on 21 September 1846 where he acknowledged the importance of such works:

'Food on reasonable terms, and employment to earn the price of same will be more conducive to the peace and tranquillity of this country than if you scattered all the Queen's troops among them.'

However, the worsening conditions in Ireland during the winter of 1846/47 and increasing press coverage of the suffering prompted Russell's government to change direction in terms of its relief policy. The public works were increasingly seen as ineffective given the rise in disease and mortality.

There were also huge demands being made on the public purse by the ever-increasing numbers on the works – over 700,000 in March 1847. Bureaucratic delays in implementing the schemes and delays in paying wages also increased the hardship with the most deserving cases sometimes going without and, in the worst-case scenario, you had the sight of the half-starved and diseased perishing on such schemes.

Daniel Macdonald's painting The Eviction, (c.1850). From the collection Crawford Art Gallery, Cork.

Soup kitchens - a "moral hazard"?

In March 1847, the Government began to phase out the public works. A Temporary Relief Act (also known as the Soup Kitchen Act) was passed by parliament the previous month which would establish soup kitchens across the country and give food directly to the people.

Despite its temporary nature, for many in government the very idea of giving food free of charge to the people constituted a moral hazard – it risked the possibility of thousands of Irish people becoming overly reliant on the state for relief.

In the summer of 1847 three million people were being fed in the soup kitchens. However, legislation had already been passed in June 1847 (Poor Law Amendment Act) that shifted the financial burden for relief from central government to local Poor Law Unions in Ireland, many of which were financially stressed and heavily in debt.

With the phased closure of the soup kitchens from late August to September 1847, the relief of famine would henceforth be financed by local taxation and would cease to be a burden on the British government.

The ruins of Bahaghs workhouse near Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry. Photo: John Crowley

It was a decision that had disastrous consequences in terms of mortality. Overcrowded workhouses were made to bear the brunt of Famine distress. The cramped conditions allowed disease to spread like wildfire. Built to deal with poverty in normal circumstances, they were unable to cope with a tragedy on the scale of the Famine. When the latter had run its course over 200,000 people had died within the confines of the workhouses.

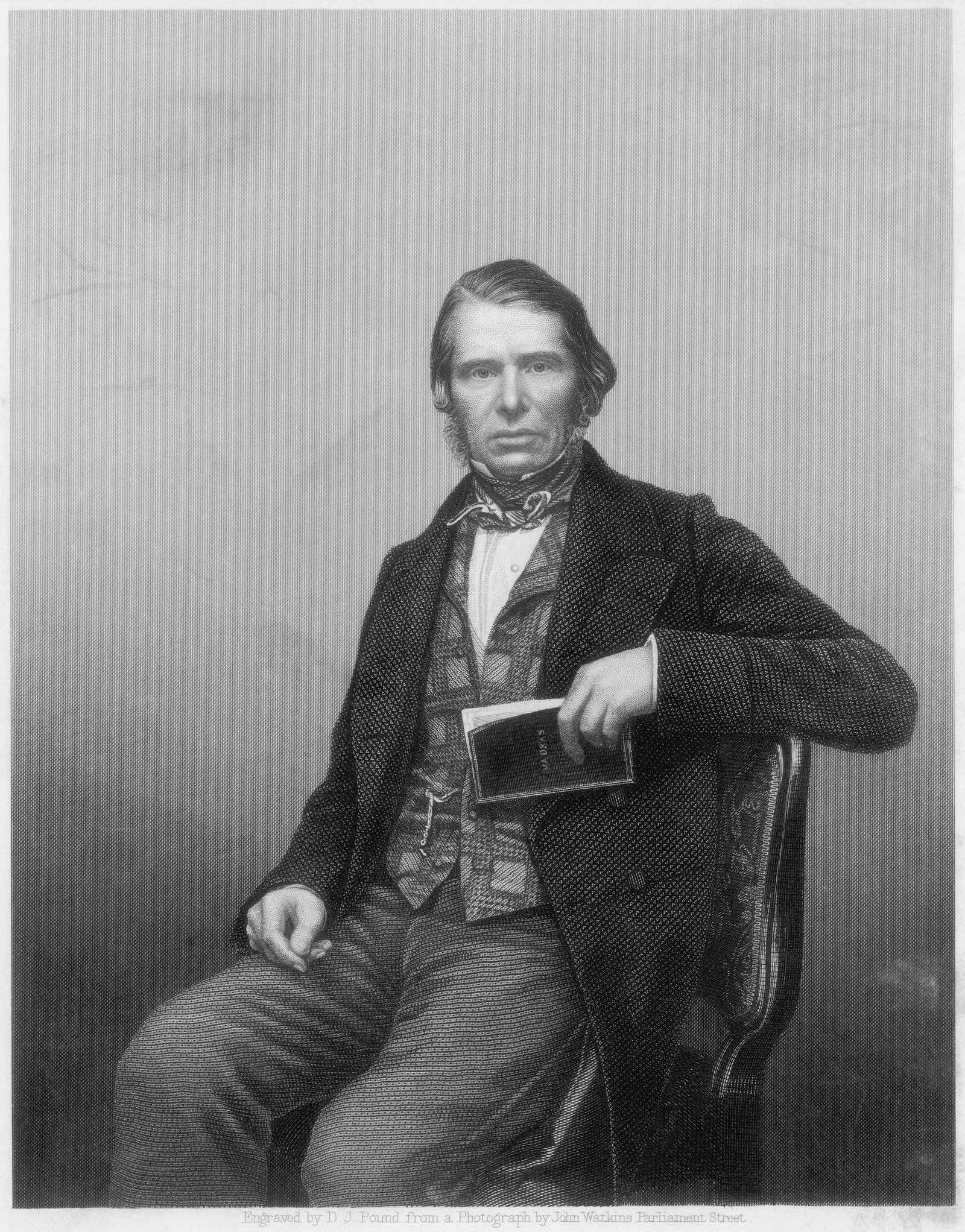

Charles Edward F. Trevelyan, K.C.B. Engraved by D.J. Pound from a photograph by John Watkins, Parliament Street. Source: Getty Images/Bettmann

'Permanent good out of transient evil'

In January 1848, a sanguine Charles Trevelyan wrote of the Famine in the past tense:

'Unless we are much deceived, posterity will trace up to that famine the commencement of a salutary revolution in the habits of a nation long singularly unfortunate, and will acknowledge that on this, as on many other occasions, Supreme Wisdom has educed permanent good out of transient evil'.

In placing the burden of famine relief on local taxation the government in effect had turned its back on Ireland. Trevelyan was adamant that relief should be a local charge and should not be a continual drain on Treasury finances.

Local rates should be responsible for local destitution and it is this mindset which dominated Cabinet thinking and prevented any further meaningful government intervention in Ireland during the remainder of the Famine.

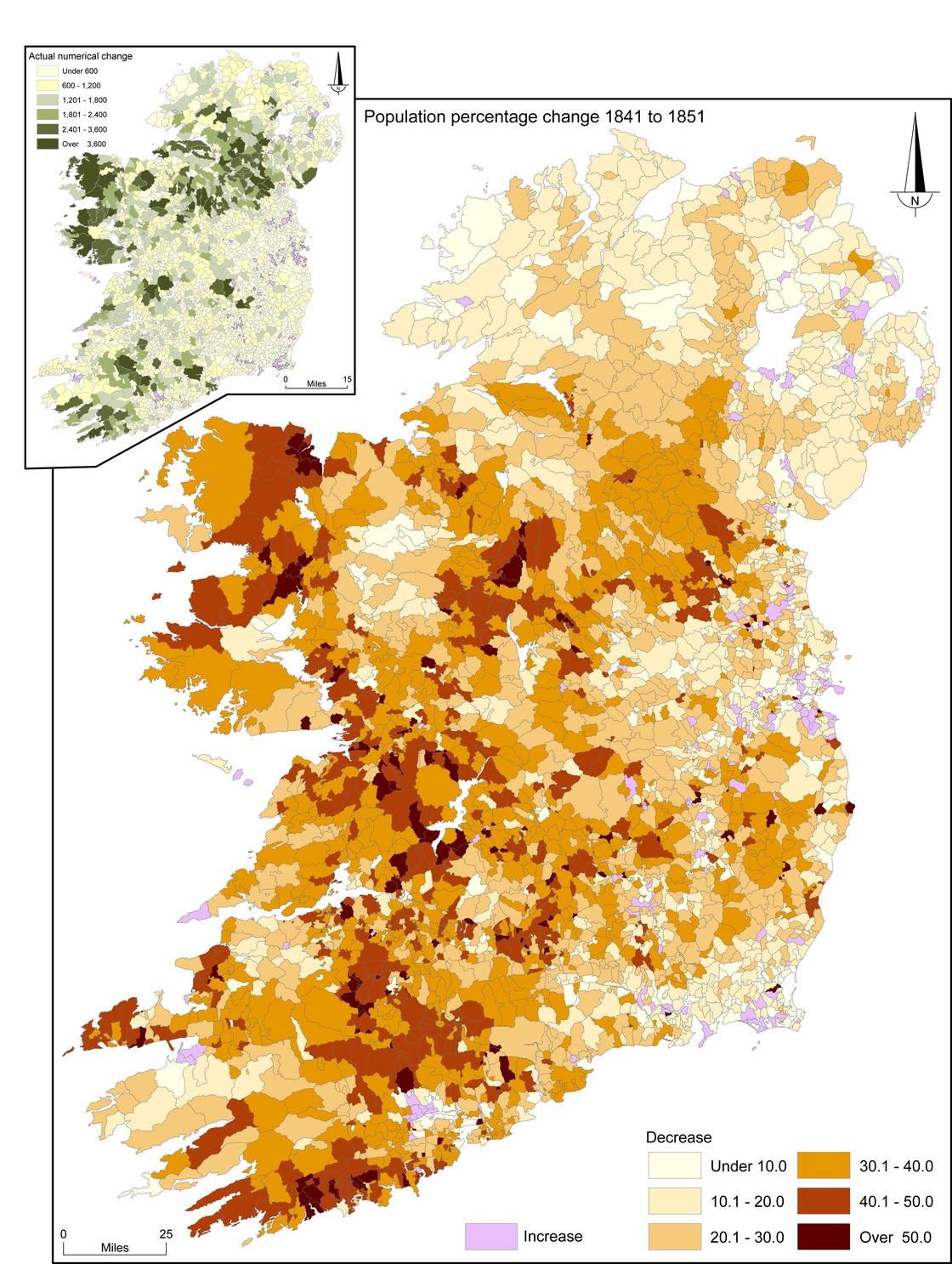

PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN THE DISTRIBUTION OF RURAL POPULATION BETWEEN 1841 AND 1851.

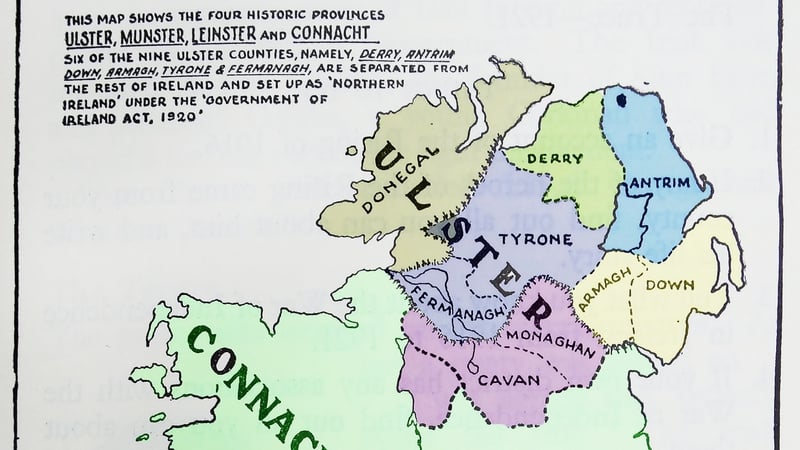

The population of Ireland declined from c.8.5m (8.7m?) in mid-1846 to 6.55m in 1851. In a limited number of parishes around Belfast, Dublin, Waterford and Cork small population increases are recorded, reflecting for the most part immigration into these city regions.

Secondly, much of Ulster north of a line from Donegal to Carlingford Lough shows the lowest population decreases –for the most part of 10 to 20%. In contrast, the heavier shading on the map reveals the contrasting fortunes of parishes which lost over 40% and in some cases over 50% (i.e. over half of the population) in this short period.

Dramatic population losses are shown from southwest Cork through much of Munster including north and east Clare, as well as the Connacht counties of Galway and Mayo. In some parishes, population losses reflect heavy mortalities, in others a significant emigration level, but in others again both excess mortality and substantial outmigration are major reinforcing agents. This map is central to any analysis of the vulnerabilities that led to so many famine death

The inadequately resourced Poor Law was no barrier to the ongoing ravages wrought by hunger and disease as blight returned and fever continued to take its toll in overcrowded workhouses. Mortality and emigration persisted while the Gregory clause allowed landlords the opportunity to clear their estates of smallholders. It was the perfect storm which flew in the face of Trevelyan's assertion that the Famine had ended.

In April 1849 Lord Clarendon, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, exasperated by the government's indifference to Ireland, wrote to Prime Minister Russell:

'Surely there is a state of things to justify you asking the House of Commons for an advance, for I don't think there is another legislature in Europe that would disregard such suffering as now exists in the West of Ireland or coldly persist in a policy of extermination'.

![Image - Sugreana cemetery near Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry where many victims of starvation and disease were buried. [Photo: John Crowley]](https://img.rasset.ie/0014b697-1600.jpg)

Sugreana cemetery near Cahersiveen, Co. Kerry where many victims of starvation and disease were buried. [Photo: John Crowley]

Wave of emigration

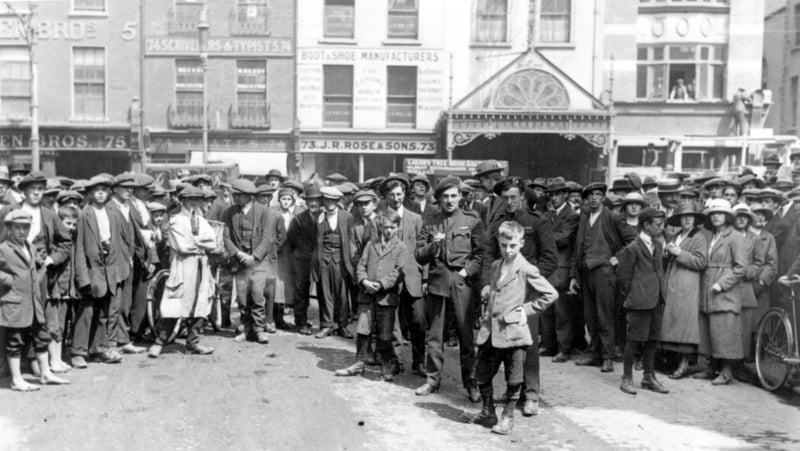

Over a half a million people were evicted during the Famine years while those with the means to leave were scattered across the globe. Many perished at sea and in quarantine stations such as Grosse Île in Quebec, Canada.

Famine conditions prevailed in parts of Ireland right up to 1852 with emigration becoming a staple of Irish life. Between 1845 and 1855 over 900,000 Irish people arrived in New York alone. Ireland continued to haemorrhage its population in the decades that followed. The Irish in America in particular would not forget easily the circumstances of their arrival.

The Great Hunger had altered forever the relationship between Ireland and Britain, a fact grasped by Oscar Wilde while on a lecture tour in the United States in 1882. He would later write of the new political landscape:

'There are some who will welcome with delight the idea of solving the Irish question by doing away with the Irish people. There are others who will remember that Ireland has extended her boundaries, and that we have now to reckon with her not merely in the Old World but in the New.'

The Famine Memorial, North Dock, Dublin.

The post-Famine decades also saw a centralising Catholic Church extend its influence on Irish society. Those amongst the rural poor who were less inclined to attend Mass before the Famine - the landless labourers and cottiers – suffered huge losses while the church increased its influence over those who survived and emerged stronger in its aftermath.

As historian Kevin Whelan points out, the Famine 'was socially and spatially selective'. Counties in the west and south were particularly devastated while the further up the social ladder, the greater the chances of survival. There was a 'hierarchy of suffering' as Cormac Ó Gráda explains and it was the men, women, and children of the poorer classes in the end who bore the brunt of the mortality.

This piece is based on the Atlas of the Great Irish Famine edited by John Crowley, William J. Smyth and Mike Murphy and its contents do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ.