To most of you, PBR probably sounds like a mid-strength beer you’d find stashed in a frat house fridge. But I’m not talking about Pabst Blue Ribbon here. Instead, this PBR—the Patrol Boat Riverine—was one of the most important fighting vessels that played a key role in protecting U.S. troops during the Vietnam War.

As the conflict escalated in the 1960s, the U.S. military realized the need for a relatively small yet nimble craft that could navigate the shallow rivers of Southeast Asia. So they reached out to Hatteras—a manufacturer of luxury yachts based out of New Bern, North Carolina—to build a prototype.

Instead of executing an entirely new design, Hatteras chopped down its existing 41-foot-long fiberglass family cruiser into a 31-foot fighting machine. A working prototype of the Patrol Boat Riverine was ready to go in just six days—very impressive, given the expansive list of modifications. Along with making the boat much shorter (and wider) than before, Hatteras moved the engines farther forward. The propellers were swapped for jets, which served to improve ground clearance and preclude the problem of props getting snagged. All of these alterations made the boat ideal for supporting troops from the shallow waterways flanking the Mekong River.

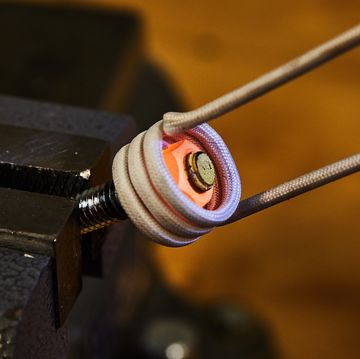

The jet propulsion system wasn’t exactly what you’d find in an F-4 Phantom II fighter plane. Believe it or not, it was manufactured by Jacuzzi. The PBR had a series of intakes underneath the hull, protected by thin mesh, to feed water to an impeller. The impeller then forced the water through stage two at incredibly high speed before shooting it out of a nozzle in the rear of the boat.

In the case of navigating shallow water, this jet propulsion is far superior to traditional propellers, with less risk of grounding out. Why? Because the only obstructions coming out the back of a jet boat are the nozzles themselves; this gives them much better ground clearance.

Task Force 116—also known as the “Brown Water Navy”—utilized its fleet of PBRs to provide fire support for troops and counterinsurgency operations. Its primary goal was to block the movement of hostile forces, which meant keeping sea lanes to Saigon open as well as intercepting those that were resupplying the Viet Cong.

Every PBR ran with a crew of four: one captain, a gunner, an engine man, and a seaman. All were cross-trained for each other’s positions—meaning the boat could operate if one or more crew members were to be killed in action. Out on the water, these boats would generally run in pairs, directed by a patrol officer.

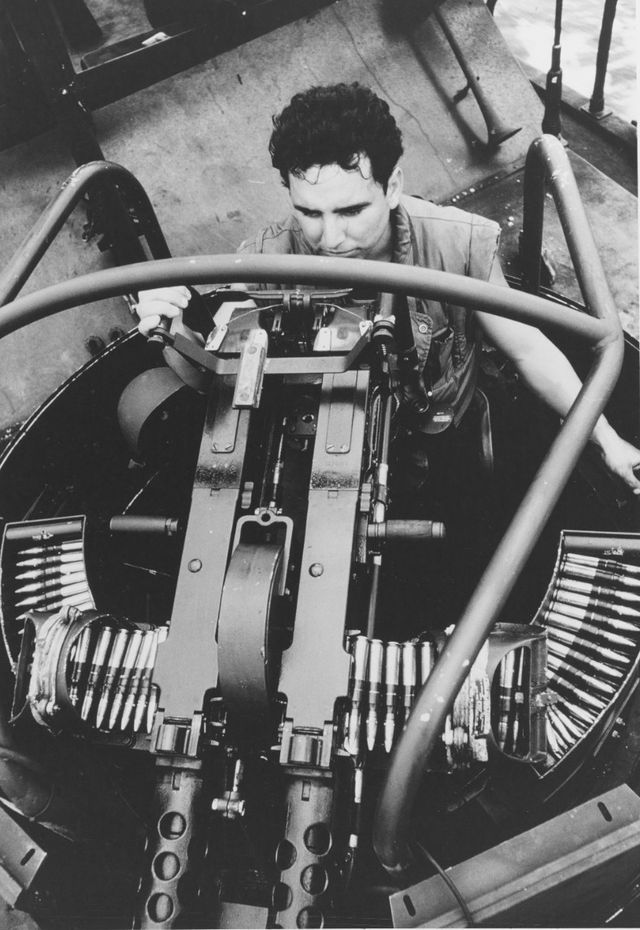

Given their relatively small size, there was only so much room onboard to mount heavy machine guns and other armaments; most featured twin .50-caliber machine guns on the bow, a .50 caliber on the back, and one or two light machine guns on the port and starboard. That might sound like a lot, but one of the PBR’s Achilles heels was its fiberglass, which wasn’t exactly, let’s say, bulletproof. Sure, there was some armor plating to protect the coxswain and the gunner on the .50 caliber at the bow. However, the PBR’s biggest defense system was its agility and speed made possible by its jet drive design.

When under attack, PBR pilots would travel at top speed close to the riverbank itself—a high-risk strategy, as one wrong move would mean running aground and becoming a sitting duck for enemy gunfire. This strategy of high-speed shock and awe made it very difficult for enemies on shore to train their weapons on the patrol boat as it flew by the riverbank.

Sadly, very few original PBRs remain. We’ve saved so many iconic aircraft like the aforementioned Phantom, the CH-47 Chinook helicopter, and even the Bell UH-1 chopper (a.k.a the Huey). Yet nobody thought to save such an interesting watercraft as the PBR. As of today, one of the only remaining patrol boats is docked at the Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina. The majority of those on the water are replicas that had to be built from the ground up using the original plans from Hatteras.

Matt Crisara is a native Austinite who has an unbridled passion for cars and motorsports, both foreign and domestic. He was previously a contributing writer for Motor1 following internships at Circuit Of The Americas F1 Track and Speed City, an Austin radio broadcaster focused on the world of motor racing. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Arizona School of Journalism, where he raced mountain bikes with the University Club Team. When he isn’t working, he enjoys sim-racing, FPV drones, and the great outdoors.