The discovery in the collection of Babylonian tablets in the Museum of a tablet containing an Ode to the Word has furnished me with the incentive for writing the following article for the JOURNAL.

Museum Object Number: B7080

Oriental and European civilization met and mingled the heritage of their long past in the centuries immediately preceding and following the foundation of Christianity. In that cosmopolitan age much of that which was true and good in the attainments of humanity emerged in the philosophies of the Stoics and the Neo-Platonists, the natural science and mathematical treatises of Pliny, Euclid, Ptolemy and Galen, and in the theology of the early Christian Church. Perhaps the philosophic principle which most effectively contributed in this fusion of human thinking, belief and practice was the evolution of the dogma of the Logos. As the theory of this philosophic principle finally emerged in the mind of that eclectic Oriental, Philo of Alexandria, it offered to all men a theory of knowledge and of revelation which broke down racial prejudice and founded at last the consciousness of universal brotherhood. And to this idea both East and West contributed in such manner that they indispensably supplemented each other. Heraclitus of Ephesus, a philosopher of the Ionian school (535-475), taught that λόγoς, the Greek word for “reason, ” is the divine law, the reality and soul of the universe. It existed from all time, this pantheistic spiritual principle, the will of god. Here was a metaphysical principle which was destined to unite all mankind in recognition of their common origin, at any rate in so far as they were capable of responding to the appeal of reason within themselves. Advancing upon the strictly mental side of this movement, the Stoics held that Logos has two aspects; the germinal Logos (λόγoς σπερματικός) or divine reason which pervades the universe, giving creation to all things animate and inanimate, has two activities. It is conceived of and known by the human reason (λόγο ενδιάθετος) and it emerges into reality, creating tangible things which human reason can know (λόγoς προφορικός). Thus the intangible spiritual power beneath all things has an active agent going forth to create and sustain the world about us. Upon purely Greek and Latin soil this idea of a pantheistic god and his intermediary agent remained a philosophic principle, of world-wide import it is true, of inestimable humanising value in overcoming racial distinctions, and national modes of thought. But it lacked the appeal to religious fervour, the power to stimulate religious devotion without which all ideas have but limited effect in human history.

In the same period another view of the active agent of God in the world began to take form on purely Semitic soil, in the ages before East and West had met and exchanged ideas. We read in a Hebrew Psalm, “By the Word of Jehovah were the heavens created, and by the breath of his mouth all their hosts, ” a composition commonly assigned to the fourth century.1 Three centuries later in the Apochryphal writing of an Alexandrian Jew the Word of God has become a personified agent. In his description of the Hebrew Exile in Egypt he writes of how the wrath of Jehovah was visited upon their oppressors. “Thine all powerful word leaped from heaven, down from the royal throne, a stern warrior into the midst of the doomed land. Bearing as a sharp sword thine unfeigned commandment, and standing it filled all things with death. And while it touched the heaven it trade upon the earth.”2 Here we have on Hebrew soil the religious evolution of an idea, complementary to the Logos idea which had arisen in Greece: on the one hand a mighty personal monotheistic god and his Word which intermediates between him and the world and on the other hand a pantheistic reason or Logos and its active agent the λόγος προφορικός. In Philo, an Alexandrian Jew and contemporary of Jesus, these two systems met. Logos as an active creative agent is identified by him with the Word of the Hebrew prophets and apochryphal writers. Henceforth Logos came to mean word. In Philo, whose writings so profoundly influenced the author of the fourth gospel and St. Paul, the Logos is the intermediary between God and man, the agent of all revelation. He dwells with God as His vice-regent; he represents the world before God as intercessor and paraclete. All this providential fusion of Greek and Hebrew philosophy and theology issued as we know in the most effective dogma of the Christian Church.

This rapid outline of a philosophical movement, which provided a formula by which Christianity appealed to Greek and Latin civilisation as well as to Oriental minds, intends only to introduce the subject which I wish to approach from a more remote source. Numerous Sumerian liturgies have been edited by the writer from other collections which prove that this idea of an agent acting as intermediary between the great gods and the world was commonly accepted by Sumerian and Babylonian hymnologists as early as 2500 B.C. They did not have the lofty conception of the Hebrews in this respect, at least the Sumerians certainly did not. With them the word of the great gods is always regarded as a word of wrath and never as a power which created the world or which reveals the spiritual truths of the universe. Not until late in Babylonian history do we find the passage, “The old men who know the. Word,” and the passage says that these are looked upon with compassion by the god of vengeance. At any rate, the idea that the word of the greatest of the gods is a personal agent who is sent forth by these deities3 to afflict mankind because of their sins was a fundamental idea of Sumero-Babylonian religion. In the later period the theologians of Babylonia may have developed this idea in a more religious and universal sense. Nevertheless the tablets have disclosed the remarkable fact that logos idea in this sense occupied a most important position in the minds of the people of Mesopotamia during the two and a half millenniums before our era. Certainly the contribution of Babylonia on the oriental side of this movement was important, perhaps the entire movement began with them so far as the personification of the Word is concerned.

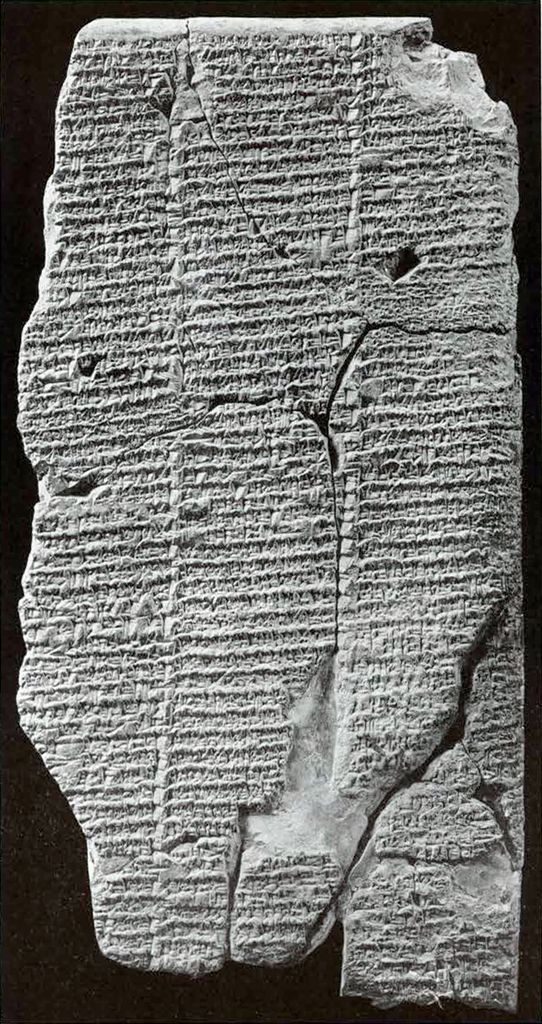

In the Nippur Collection has been found the right half of a very large literary tablet, No. 7080, photographed with this article. The tablet originally carried five long columns on each side, or ten columns of about fifty lines each. It carries a liturgy of about .500 lines, being a lamentation on the destruction of the famous city of Ur, known to laymen chiefly as the birthplace of Abraham and seat of the worship of Sin the Moon god. Like all other civic and national calamities, the fall of Ur in the twenty-fourth century at the hands of the Elamites, gave rise to the composition of long musical threnodies, henceforth employed as liturgies in the temples throughout the land of Sumer. This long liturgy, which is divided into about twelve melodies, belonged to the prayer books of Nippur and was probably composed in the Isin period. The dynasty of Isin succeeded to the hegemony of a greater part of Sumer, when the dynasty of Ur passed away. The famous city Nippur then came under their domination. We may wonder why a lamentation on the destruction of Ur should have been employed in the succeeding ages in the breviaries of all Sumerian and Babylonian temples. This particular liturgy which has been found in the Nippur Collection has not yet been identified in the prayer books of Assyria and Babylonia, but similar lamentations on Ur, Erech and other cities were employed as public liturgies in all succeeding ages and in lands remote from the ancient cities where these calamities occurred. The explanation is to be found in the fact that these specific sorrows were taken as types of all human sorrows; especially the woes which befall cities sacred in the religious traditions of races become the subject of prayers in the official breviaries.

The new Nippur tablet has as its fifth melody an ode to the Word or Spirit of Wrath which is unique among all published liturgies. For here the theologians already, in the twenty-third century B.C. not only describe the Sumerian Logos as a messenger of the Earth God but they speak of two minor spirits in his attendance. This is certainly an unexpected phase of the subject and shows that Babylonia had developed advanced ideas concerning the personification of the Word. The ode to the Word follows, in this liturgy, a song of the weeping mother goddess in which she is represented wailing over the ruins of Ur. Of the avenging Word she says:

The foundations it has annihilated and reduced to the misery of silence.

Unto Anu [The Heaven god] I cry, “how long?”

Unto Enlil [The Earth god] I myself do pray.

“My city has been destroyed” will I tell them.

“Ur has been destroyed” will I tell them.

May Anu prevent his Word.

May Enlil order kindness.

These lines from the third melody will illustrate the lugubrious character of the Sumerian public prayers and the destructive character which they first assigned to the Word. At the end of this the fourth melody a single line antiphon divides it from the fifth song.

“Her city has been destroyed, her ordinances have been changed.”

This intercalated musical line sounds so much like the remarks of the choir in a Greek play that we are induced to believe in a certain amount of staging for histrionic effect in these long musical liturgies. Perhaps a priestess actually stood forth when the musicians reached the fourth melody and took the part of the divine mater dolorosa. Now follows the remarkable fifth melody to the mighty Word of Enlil. It is here called, throughout, the spirit of wrath, an epithet by which it is often referred to in other liturgies.

Enlil utters the spirit of wrath and the people wail.

The spirit of wrath has destroyed prosperity in the land, and the people wail.

The spirit of wrath has taken peace from Sumer and the people wail.

He sent the woeful spirit of wrath and the people wail.

The “Messenger of Wrath” and the “Assisting Spirit” 4

into his hand he entrusted.

He has spoken the spirit of wrath which exterminates the

Land and the nation wails.

Enlil sent Gibil5 as his helper.

The great wrathful spirit from heaven was spoken and the people wail.

Ur like a garment thou hast destroyed, like a . . . thou hast scattered.

About half of this song to the Word has been lost on the tablet, but the one line antiphon sung either by a priest or the choir is preserved.

The spirit of wrath like a lion [rages] and the nation wails.

Nearly all the Babylonian liturgies have at least one song concerning this personified word of the gods. Religiously the conception is not high and the persistence with which they repeat these doleful uninteresting songs from age to age during a period of 3000 years only emphasizes the dreariness of their official orthodoxy. Nevertheless the historian of religions must take account of this phase of the origin and evolution of the logos idea. Babylonia at least first personified the word of the gods. This dogma and belief arose here many centuries before we have any trace of it in the Hebrew, where it appears not only as an agent of wrath but as agent of creation, the verbum creator. The latter aspect may have been attained by the Babylonians, and perhaps even by the Sumerians. This Nippur tablet has thrown a new light upon this doctrine as it was chiefly held by the theologians of Sumer in the Isin period.

S.L.

1 Psalms 33, 5.↩

2 The Wisdom of Solomon, 18, 15-16. See HOLMES in CHARLES’ Apochrypha and Pseudepigrapha, Vol. I, 565. ↩

3 Usually the Heaven God and the Earth God.↩

4 Names of two divine genii who attend the Word in his mission on earth.↩

5 The fire god.↩