Inside Henry Darger’s Outsider Art

The incredible story of how an inconspicuous janitor gained posthumous fame for his life’s oeuvre, and became one of the leaders of outsider art

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Oct 04, 2022

Henry Darger was a hospital janitor from Chicago. He lived in a second-floor rented room in the Lincoln Park section of the city, until he moved into St. Augustine's Home for the Aged. Ostensibly, he was just another poverty-stricken old man who kept to himself. Until shortly before his death in 1973, when his landlord and notable Chicagoan photographer, Nathan Lerner, discovered Darger’s unbelievably vast and impressive oeuvre, which included thousands of pages of writing and hundreds of paintings. This fortuitous unearthing of the recluse’s work is the only reason the artistically minded public knows of the man today, and why Darger’s work has become one of the most poignant and celebrated examples of outsider art.

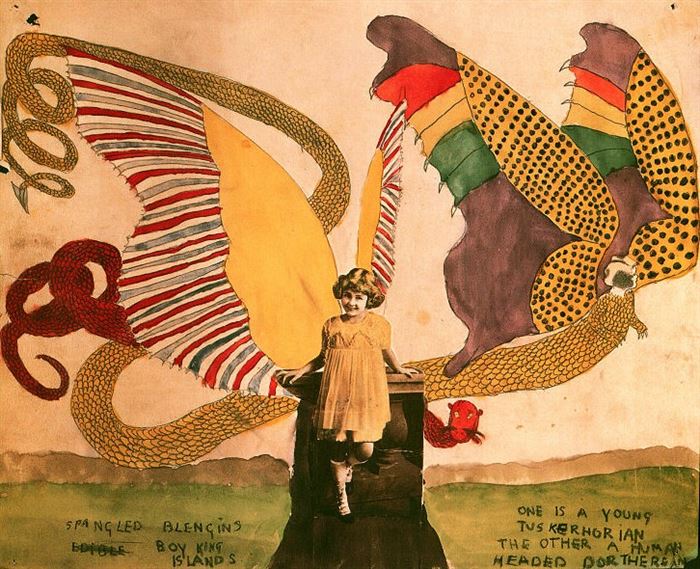

Spangled Blengins. Boy King Islands. One is a young Tuskerhorian the other a human headed Dortherean, undated, Watercolour, pencil, and cut-and-pasted printed paper on paper, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

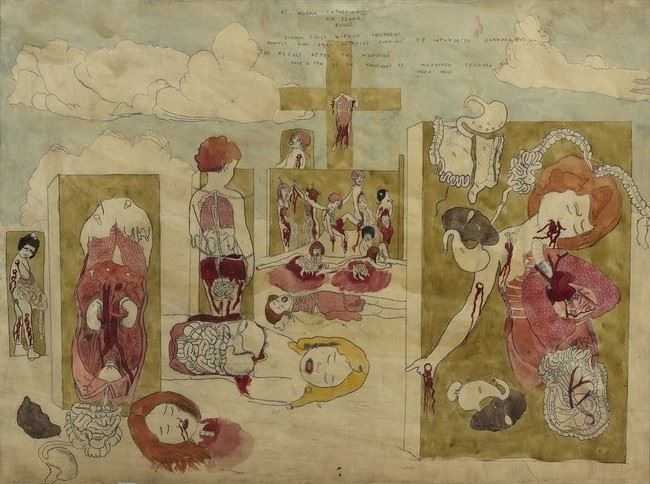

The artistic world of Henry Darger is one that is immensely ambivalent. Idyllic depictions of little girls in vales of wildflowers lead one unknowingly into fields of blood and the most visceral carnage. It is a world that is both endearing and repulsive, a world that was always intended to stay a complete secret.

At Norma Catherine via Jennie Richee witness childrens bowels…, undated, watercolour and pencil on paper, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Darger’s childhood was plagued with hardship and tragedy. He was born in the Windy City in 1892 and lost his mother to complications during the birth of his younger sister when he was not even four years of age. The new-born child was put up for adoption, leaving Henry with his ailing father, until, not being able to be sufficiently cared for, he was sent to a Catholic home for boys. Here, he soon earned the nickname “Crazy”, due to the fact that he often made unusual gestures with his arms and emitted strange sounds with his mouth. When he was 12 years old, he was examined by doctors and sent to the Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children in Lincoln, Illinois. The institution implemented forced child labor, and severe punishments were executed on any child who stepped too far out of line.

At Mc Calls run. Hands of fire, undated, watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The one way in which young Henry could escape his misery-wracked childhood, was to fall headfirst into a world of imagination. Storybooks were always a welcome gift from his father, and Henry spent what little pocket money he acquired on paints. He would spend hours staring out of the front window, watching the winter snow fall outside. This proclivity of living in fictional or imaginative worlds was something that stayed with Darger all his life. So did the sense that children invariably suffered at the hands of adults – especially strangers. Together, these formed part of the drive for the creation of Darger’s magnum opus, a 15,145-page manuscript with hundreds of accompanying illustrations, named In the Realms of the Unreal. Darger was also deeply touched and inspired by a photograph of Elsie Paroubek, a five-year-old girl who was kidnapped and murdered in 1911. The newspaper-clipped picture of little Elsie went beyond mere inspiration and bordered on an obsession for Darger. He was distraught when he eventually lost the photograph, and despite earnest endeavors, was never able to source another.

Henry’s father died when he was seventeen, and after several unsuccessful attempts, he managed to escape from the misery of the asylum and make his way back to Chicago. It was during this time period that Darger first found work as a hospital janitor, and also when he first began composing his manuscript.

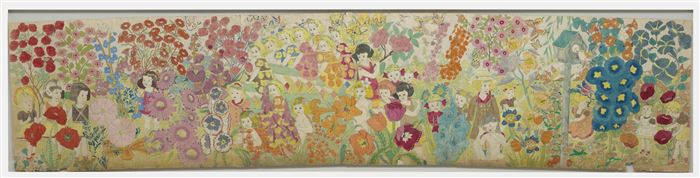

Untitled, undated, watercolour and pencil on paper, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

In the Realms of the Unreal is a surreal and epic fantasy, that follows ‘the Vivian girls’ – seven princesses who assist in a rebellion against child slavery. Darger created panoramic battle scenes using paper from magazines and coloring books. The Vivian girls were often accompanied by their cohorts – a battalion of naked prepubescent girls who strangely possessed male genitalia. These battle scenes are often especially violent, with images of evisceration, decapitation, and crucifixion. These panoramas of utter brutality and unrelenting slaughter, after the tranquility of skipping ropes and fields of wildflowers, are a significant reason why Darger’s work is so potent. His masterfully executed dynamics, alongside his all-too-real understanding of the fragility of human life, render his pieces superlatively visceral.

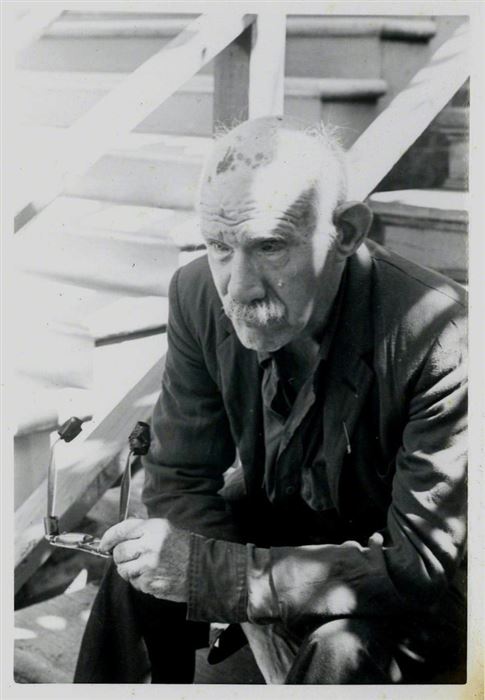

Photograph of Darger, taken by David Berglund in 1971

During his life of seclusion, Darger was a passionate collector of ephemera, including comic books, magazines and newspapers, and picture cards of Catholic saints. This tendency to collect and hoard, meant that he had a near-endless supply of inspiration and access to create his work. He traced from comic books, clipped pictures of soldiers from magazines, and took source images to the local drug store so the photography counter could make enlargements. The result was that Darger’s work was eclectic, and very much ahead of its time.

a) At Jennie Richee the Blengins stay under shelter b) Lightning strikes the crazy outfit again, undated, watercolor, pencil, and ink on paper, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Darger worked primarily in watercolor when he painted, his delicate palette is rich in flower-petal pastels, exhibiting innate skill. He would often balance two or three bright shades against darker tones and monochromatic colors, creating an underlying malevolence that lurked in the background, and threatened to overwhelm his subjects completely - which it invariably did only a few panels away.

Darger worked with a fevered passion, an indisputable earnestness, with a palette both tender and violent, leaving one unsettled and ambivalent. Was Darger simply a lonely old man, or did something much darker lurk inside of him? We will never truly know, but, as Darger himself wrote in 1950: “The world needs a narrative.” He took that one step further, narrating his own world. A world we are very privileged and exceptionally lucky to be able to even peek inside of today.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page