Scientist of the Day - Robert Serber

Robert Serber, an American physicist, was born Mar. 14, 1909. He studied engineering at Lehigh University, got his PhD in physics at the University of Wisconsin—Madison in 1934, and then headed for Berkeley to do post-graduate work with Robert Oppenheimer. He taught at the University of Illinois from 1938 to 1942, when World War II came calling, and he was invited by Oppenheimer to become part of the Manhattan Project. In the summer of 1942, he was part of a workshop at Berkeley that discussed the problems of building an atomic weapon for use in wartime.

In April of 1943, about other fifty physicists and engineers converged on Los Alamos, New Mexico, also invited by Robert Oppenheimer to become part of this mysterious Manhattan Project. Serber was asked by Oppenheimer to give five lectures to the new arrivals, explaining exactly what was known to date about nuclear fission and the possibilities of creating a weapon of destruction, and what needed to be done by the group. But until Serber's first sentence of his first lecture, no one except Oppenheimer and Serber and a few others knew why they had been assembled out in the middle of the desert high country, behind a barbed wire fence. The first sentence stated:"The object of the project is to produce a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb in which the energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission."

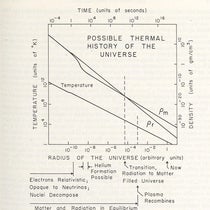

The lecture series discussed such matters as the energy released by a nuclear chain reaction (10 million times that of a conventional explosion), the kinds of materials that might be used for an explosive (plutonium was so new that its name wasn't even known to Serber, who just called it by its code name, “49”), and – the real conundrum – how to safely and efficiently assemble “fissionable materials” into a “gadget” (Serber was told by Oppenheimer, after his first sentence, that they weren’t to use the word “bomb”). After the conclusion of each lecture, Ed Condon wrote up his notes, with Serber’s help, which were then mimeographed in a rather condensed form (only 26 pages for the total). A copy was then given to every newcomer to Los Alamos (the initial number of 50 would swell into the thousands in the next two years). The lectures were called, rather impishly, The Los Alamos Primer, as if it were an ordinary schoolbook, and it was given the official label: Los Alamos report LA-1, the very first publication of the new facility. The Primer was a top-secret document for many years, but it has been declassified for a long time, and you can leaf through the mimeographed pages at several web sites, including this one.

As I read through the Primer as best I could – my physics days are long behind me – I was struck by several interesting features of the lectures. First, a great deal was already known in 1943, before the Manhattan project was even underway. It was pretty clear that a small mass, say 1 kilogram, of U235 (the rare isotope of uranium, called “25” in the Primer) would produce a yield of 20,000 tons of TNT. It was known that once a “critical mass” of U235 had been accumulated, a chain reaction would naturally result, so the U235 would have to be kept in separate and smaller masses until the crucial moment. The principal problem was how to assemble the critical mass fast enough, so that it didn’t pre-detonate and fizzle out. Serber guessed in the Primer that some sort of uranium "gun", which fires a bullet of uranium into a sub-critical mass at high speed, would do the trick, and that is exactly the mechanism that Little Boy, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, would later use. But no one foresaw how hard it was going to be to separate U235 from common uranium. All of the plants at Oak Ridge were not going to produce enough U235 for more than just the one bomb, which means they couldn’t even test Little Boy before they used it. Second, no one yet had an inkling how to make an "49" bomb, one using plutonium. They knew that a "gun" wasn't going to work with plutonium, which is much more reactive than uranium, which meant you couldn't shoot a plutonium bullet fast enough to prevent the plutonium from pre-detonating, so some other mechanism was needed. And that is what much of the Manhattan Project would be concerned with for the next two years, figuring out that an implosion design was the only workable possibility, and then engineering shaped explosives that would compress a non-critical shell of plutonium into a small hyper-explosive sphere almost instantly. The test at Trinity in 1945 would be the first proof of the success of the implosion design. The bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Fat Man, would be a much more sober demonstration. Serber, incidentally, was the one who named Fat Man and Little Boy.

I have often wondered what it would have been like for Serber, giving these lectures to the likes of Oppenheimer, Condon, Hans Bethe, and Richard Feynman. Feynman was still an unknown, but Bethe and Oppenheimer were already giants in the field. Serber must have had a great deal of confidence, and was probably fairly imperturbable and thick-skinned, since physicists like Bethe and Feynman pulled no punches. He was also very smart, and no one knew the material better, which is why Oppenheimer chose him.

In 1945, Serber was part of Project Alberta, the mission to deliver the atomic weapons to the Japanese theater and assess the damage; it was headquartered on Tinian, an island in the Pacific, where our third image was taken. Serber is on the right; Luis Alvarez, who would win the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968, is in the center.

Detail of group photo of Shelter Island Conference, 1947. Robert Serber is the short man in the second row, just left of center, in front of the drapes; Hans Bethe, with the frizzy hair, is just to the left of Serber, in the rear; Robert Oppenheimer is the fifth from the right, in the second row; Richard Feynman is third from the right, in the rear, Institute for Advanced Study archives (albert.ias.edu)

In looking for other photographs of Serber, I chanced upon a group photo taken in 1947 at the first Staten Island Conference in quantum physics, the first post-war meeting of nuclear physicists. You can see the entire photograph of all 50 participants here; I show instead a detail of the right third, where you can spot not only Serber, but Bethe, Oppenheimer, and Feynman; they are identified in the caption (fourth image).

Detail of group photo of Shelter Island Conference, 1947. Robert Serber is the short man in the second row, just left of center, in front of the drapes; Hans Bethe, with the frizzy hair, is just to the left of Serber, in the rear; Robert Oppenheimer is the fifth from the right, in the second row; Richard Feynman is third from the right, in the rear, Institute for Advanced Study archives (albert.ias.edu)

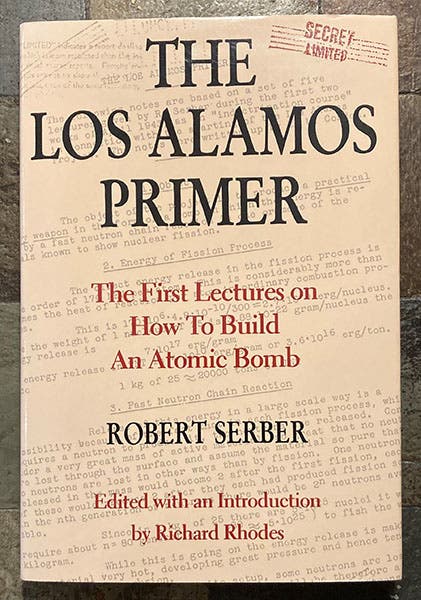

The Los Alamos Primer was republished in 1992 in a much more readable form, with an extensive series of historical notes by Serber himself, and a very good introduction by Richard Rhodes, author of The Making of the Atomic Bomb (1987) (fifth image).

William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.