Review: Are just four Sam Francis paintings enough for a landmark show at LACMA?

Is a major exhibition possible with just four significant paintings? Maybe. But, if so, “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing,” newly opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, isn’t it.

Ever since Benjamin West went to England in 1763, never to return to his native Pennsylvania, American painters and sculptors have traveled abroad to study and work, including in France, Germany, Italy and elsewhere, mostly in Europe. Sam Francis did too. After graduating from UC Berkeley following military service in World War II, San Mateo-born Francis headed off to Paris, courtesy of the G.I. Bill.

He stayed for around five years. But his experience there was rather different than most.

A rudimentary French speaker who soon gained fluency, he moved easily in the 1950s Parisian art world. He befriended not just French artists and other American expats, but Japanese painters more comfortable studying there — for obvious reasons — than in the United States. In 1957, Francis made his first trip to Tokyo.

It was not his last. Eventually he maintained a studio in Japan. His primary collector was Japanese oilman Idemitsu Sazō, and two among his five wives were Japanese (one his collector’s daughter). The LACMA display means to show the profound impact that Japanese art, traditional and contemporary, had on the development of his abstract sensibility as a painter.

It does — sort of. But not nearly in satisfying ways.

In addition to Tokyo, the California artist, who died in 1994 at 71, kept studios at various times and for varying periods in Santa Monica, Paris, Mexico City and Bern, Switzerland. Disparate cultural attitudes were manifest not only in his art but in his central role more than 40 years ago in the creation of the Museum of Contemporary Art. Francis was instrumental in the selection of architect Arata Isozaki to design his first American building and of Swedish-born Pontus Hultén, former director of Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou, to take the MOCA helm in Los Angeles.

The greatest leaps in his development as an abstract painter came through absorption of the liberation of color in French Fauvism and the spatial transformation of pictorial illusionism in Claude Monet’s lily ponds, as well as from traditional Japanese aesthetics. A friend describes Francis as America’s first truly international artist. She’s probably right.

For all these reasons, “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing” ought to be a significant addition to scholarship on the artist. His four-decade interest in Japanese paintings and printmaking is no secret. But — surprisingly — not until now has an exhibition been devoted to the subject, according to LACMA.

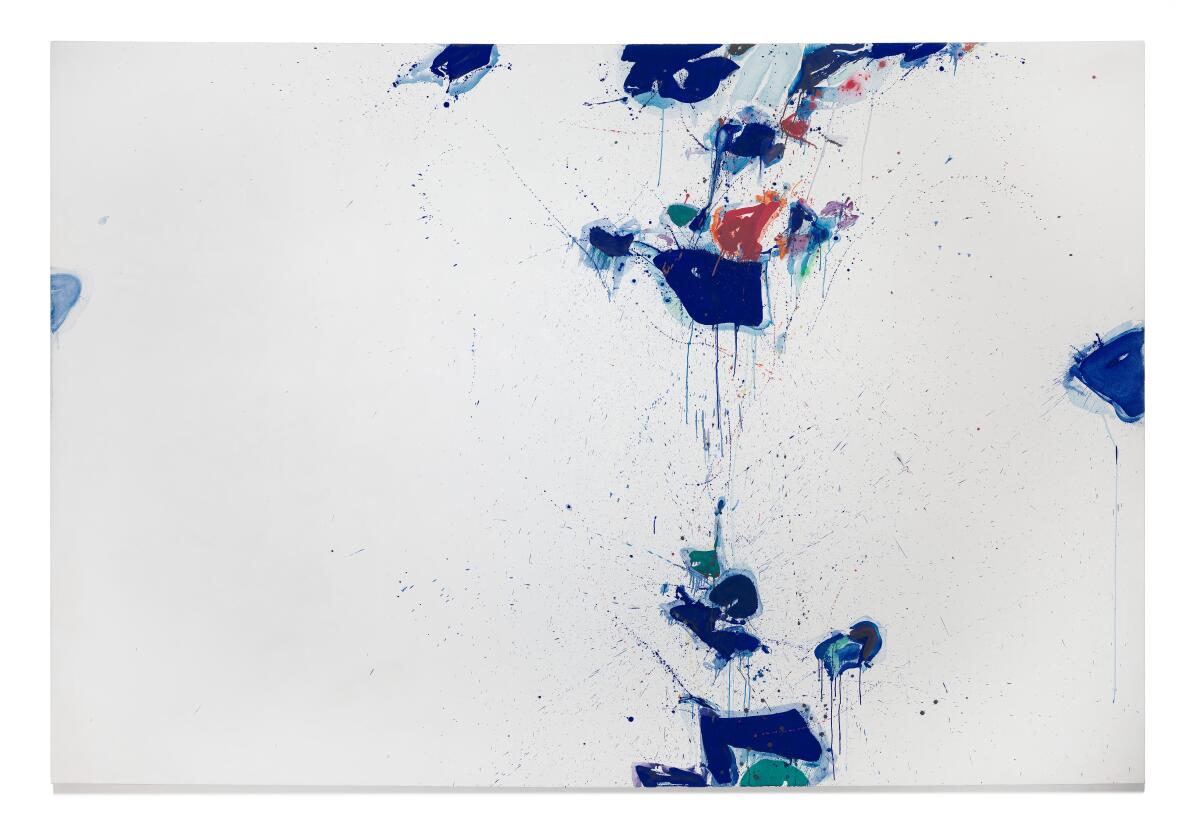

The current exhibition — organized by LACMA curators Hollis Goodall and Leslie Jones, with guest curator Richard Speer — juxtaposes Francis’ work with scores of Japanese scroll paintings, prints and calligraphy. Unfortunately, few significant Francis paintings are on view. The most compelling room is the entry. The artist’s monumental canvas “Towards Disappearance,” painted in the year after his first Japanese sojourn, dominates.

Fourteen feet wide and 9 ½ feet tall, the mural features organic liquid shapes of mostly cobalt blue that seem to cascade from — or sink into — a vast field of bright white oil paint, trailing spatters of color as it does. (Think of an abstract mountain waterfall.) Opposite, standing on a low plinth, an exquisite pair of Yamaguchi Soken six-panel screen paintings from the late 18th or early 19th century show a landscape of elegantly arrayed flowering plants spanning four seasons, set against a gold background.

The lustrous, light-reflective gold unmoors the painted living objects from earth or sky, and thus from ordinary time, establishing an ambiguous space for nature. The juxtaposition with the Francis painting seems to intend a connection to his use of a flat, uninflected field of white as the ground for his blue forms. Yet expanses of amorphous space had been a central feature of Francis’ work for many years before he set foot in Japan. “Grey,” a large 1951 abstraction at the Museum of Contemporary Art, is but one important example.

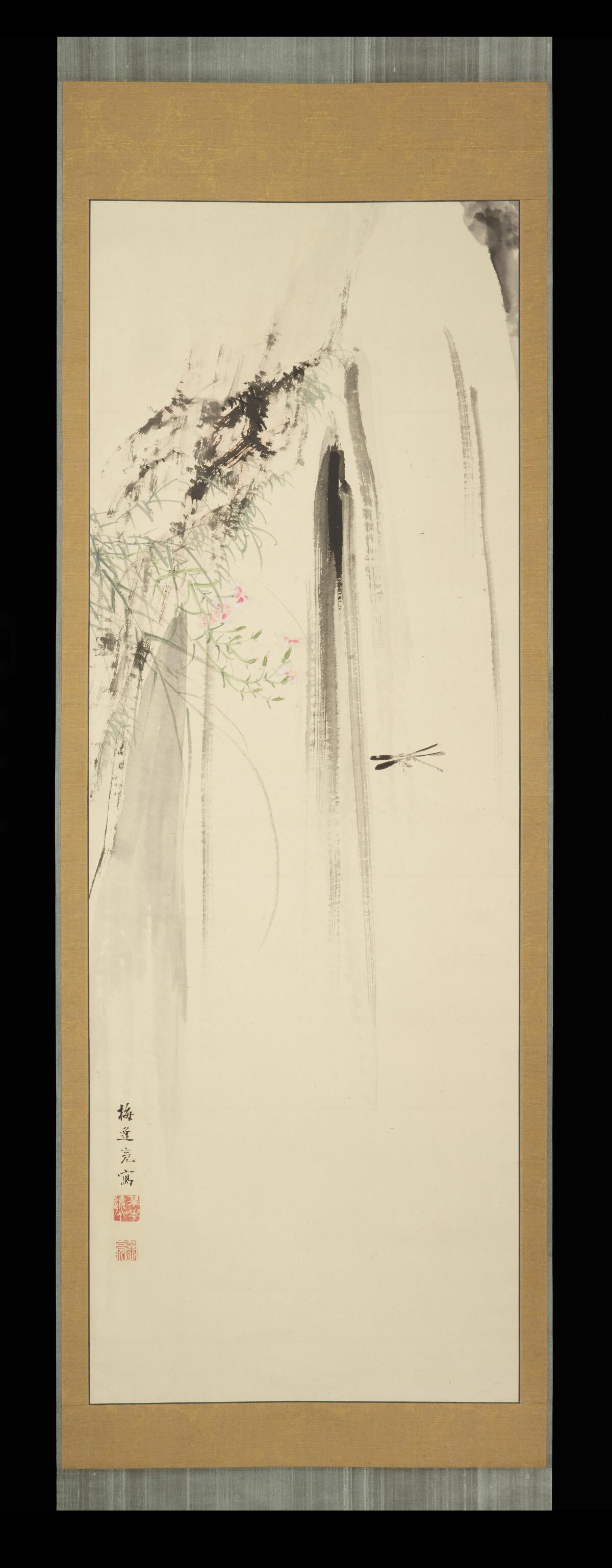

Certainly his work displays affinities with the cosmic energies in Japanese art. A gorgeous 1958 watercolor, “Untitled (Japan Line),” trails dribbles of crimson color akin to the vaporous composition adjacent in Yamamoto Baiitsu‘s 19th century “Dragonfly and Pinks With Waterfall,” a lovely hanging scroll.

And of course, Francis was hardly the first American to be attracted to the complexities of Japanese aesthetics. Those had been influential to American avant-garde artists since the start of the 20th century. Arthur Wesley Dow — who taught Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Burchfield, Max Weber, Gertrude Käsebier and many more — was steeped in the genre, having worked with the great Asian art curator Ernest Fenollosa at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Half a century later in L.A., the 1950s geometric abstractions of John McLaughlin are especially notable, exploiting the Japanese principle of spatial intervals known as ma. Japanese aesthetics were integral to the Modern American artistic language.

Only four significant paintings by Francis are included in the show. Even though the artist was prolific, these four are installed amid more than 40 Modern and historical works by Japanese artists. (One, Suga Kishio, was his Tokyo studio assistant. Oddly, there’s nothing by Imai Toshimitsu, a close friend and colleague he met in Paris.) Mostly, the dearth of Francis’ major works leaves you wondering just what the connections might be and how — or if — they operate.

Francis made a lot of prints. In 1970, he established a lithography printing studio in Santa Monica, and the exhibition relies on several dozen. It comes across as a kind of introductory undergraduate classroom discourse: Compare and contrast.

His 1966 “Sky Painting,” in which Francis performed a kind of transient abstract skywriting over Tokyo Bay with colored smoke emitted from helicopters, is likened to calligraphy in real space; but it’s represented by a wall-size photo enlargement that is difficult to read visually, plus some documents. The evanescent “Sky Painting” did predate by a year Robert Morris’ influential atmospheric sculpture made of billowing “Steam,” and it predated by two years Judy Chicago’s first outing with ephemeral colored smoke. But, for all three performance-based works, you had to be there. The show would be better served if another great painting filled that big photo wall.

If it feels confused and thin, that’s probably because the show is makeshift. Just over half of the current exhibition is drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. Originally intended to open in a different form in 2020, that version was shelved due to the pandemic. The catalog, somewhat altered, is presented as a digital supplement on the LACMA website (Speer’s essay is especially worthwhile). Surely the epic health disruption explains some of its limitations.

'Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing'

Where: LACMA, 5905 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles

When: Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays 11 a.m.-6 p.m., Fridays 11 a.m.-8 p.m., Saturdays and Sundays 10 a.m.-7 p.m. Closed Wednesdays. Through July 16.

Info: (323) 857-6000, lacma.org

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.