When most people hear the name “Liberace,” certain images come to mind. Perhaps the image of a flamboyantly dressed man in a sequined cape. He would be seated at a rhinestone-studded Grand piano playing an almost schizophrenic combination of Classical, Pop, and Show Tunes.

A man whose garish appearance easily calls into question his standing as a serious, Classical pianist.

Liberace was not only a highly accomplished Classical performer prior to turning his talents to the entertainment business. But he was also one of only a handful of concert pianists who could perform dozens of complicated Classical pieces from memory alone.

His musical tastes and aspirations, however, ran far beyond the limitations of Classical music.

Born to Destiny

He was born Władziu Valentino Liberace on May 16, 1919, in West Allis, Wisconsin. His parents were Salvatore Liberace (an immigrant from the Lazio region of central Italy), and Frances Zuchowski (a woman of Polish descent) from Menasha, Wisconsin.

Liberace was an identical twin whose brother died at birth.

He had three surviving siblings: an older brother George (a violinist), a sister Angelina, and a younger brother Rudolph Valentino Liberace. Both Liberace and his youngest brother were named after the famed actor “Rudolph Valentino.” His mother was an ardent fan of silent films.

According to multiple accounts, Liberace was born with a cowl (caul) covering his head and face. This is a piece of birth membrane said to predict greatness. As observers of old-world superstitions, Liberace’s parents likely assumed it was divine providence that their son would become famous.

Both parents had a background in music. Liberace’s father was a French horn player who performed with the Philadelphia Symphony and John Philip Sousa`s concert band. His mother was a former concert pianist of some renown.

It was Salvatore who encouraged his family to music careers. Frances believed music lessons (and even a phonograph) were extravagances, considering the state of the economy. But Salvatore’s love of music won out, ultimately inspiring Liberace to create a family musical legacy.

Education

By the age of four, Liberace demonstrated not only a talent for the piano, but for memorizing complicated pieces of music. He was soon recognized as a child prodigy.

It was decided that he would forego traditional education in favor of musical training. At age seven he began the formal study of music at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music in Milwaukee.

As a boy, Liberace suffered from a speech impediment that made him the target of teasing from neighborhood children. By his teens, he had developed effeminate mannerisms that drew mockery. This, however, only made Liberace’s resolve to become a master pianist even stronger.

In addition to ongoing piano lessons with music teacher Florence Kelly (who contributed to Liberace’s musical development for 10 years), Liberace gained his first experience performing publicly. He started playing popular music in theaters (accompanying films), on local radio, for dance classes, clubs, and weddings.

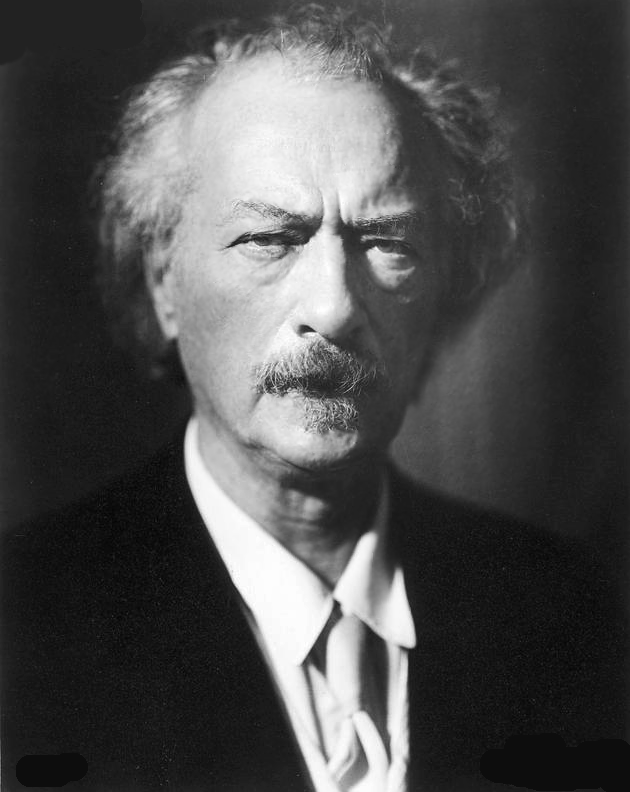

Having discovered the music of famed Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Liberace set out to master the virtuoso’s technique.

In that his father considered exposure to live performances as important as formal training, Salvatore took his children to concerts whenever possible. One such concert resulted in Liberace meeting Paderewski backstage at the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee.

Of that encounter, Liberace would later say, “I was intoxicated by the joy I got from the great virtuoso’s playing. My dreams were filled with fantasies of following his footsteps . . . . Inspired and fired with ambition, I began to practice with a fervor that made my previous interest in the piano look like neglect!”

Impressed with the young Liberace’s natural aptitude for music, Paderewski became the boy’s mentor—as well as a close family friend.

A Budding Career

In 1934, at the age of 15, Liberace began playing jazz piano with a group of school-age kids called The Mixers. And later, with other local groups who performed in cabarets and strip clubs.

Though his father and mother disapproved of that environment, it was the time of the Great Depression. And their son was contributing to the family income.

For a time, Liberace adopted the stage name, “Walter Busterkeys.” Even at this early stage of his career, he started showing a flair for fashion and bold attire to draw attention.

In 1937, Liberace competed in a formal Classical music competition. He was praised for his “flair and showmanship.”

Two years later, after a traditional Classical concert held at La Crosse Concert Hall, Liberace played his first requested encore. He chose the popular comedy song, “Three Little Fishies,” a song he played in the styles of several different Classical composers—to an audience ovation.

On January 15, 1940, the 20-year-old Liberace played with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra at Pabst Theater in Milwaukee. This was where, ten years earlier, he’d watched famed Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski play.

He performed Liszt’s Second Piano Concerto, for which he received outstanding reviews. This led to a tour of the Midwest, performing Classical music.

Finding His Groove

Beginning in 1942, Liberace moved away from straight-forward Classical performance and began incorporating pop music into his act. He started to create the stage persona that would define him for the remainder of his career and personal life.

By the mid-to-late-1940s, Liberace was performing in nightclubs in major cities across the US. He was becoming less of a Classical pianist and more of an entertainer and showman.

His act had become a whimsical combination of Classical and Pop. He was marrying Chopin with American standards like “Home on the Range,” for example.

For a short time, Liberace played piano along with a phonograph on stage. This was a gimmick that helped him gain attention.

By this point, his musical performance was different from every other Classically-trained pianist of the time. He did something no other pianist did: he interacted with the audience. He took requests, cracked jokes, and even singled out audience members to join him on stage for impromptu piano lessons.

As his performances became more of a spectacle, he began paying greater attention to staging, lighting, and overall presentation.

Films and Media Attention

In 1943, Liberace began appearing in “soundies.” These were three-minute musical films spotlighting a single performance, like music videos of the 1980s. Recreating two flashy tunes from his nightclub act, he performed “Twelfth Street Rag” and “Tiger Rag,” billing himself as Walter Liberace.

In 1944, Liberace made his first of many appearances in Las Vegas. It later became his primary venue.

The following year, Liberace made his first appearance at the famed Persian Room. Variety magazine proclaimed, “Liberace looks like a cross between [actors] Cary Grant and Robert Alda. He has an effective manner, attractive hands which . . . he spotlights properly, and withal, rings the bell in the dramatically lighted, well-presented, showmanly routine.”

Similarly impressed, the Chicago Times reported, “[He] made like Chopin one minute and then turns on a Chico Marx [of the famed Marx Brothers] bit the next.”

A Showman Extraordinaire

By 1945, Liberace was making the final visual adjustments to his act. He was adding what would become his piece de resistance.

This would be a candelabrum placed prominently on top of his piano. This was a prop he’d seen used in the Chopin biopic, A Song to Remember (the 1945 biographical film about Frédéric Chopin).

This, along with a flowing pompadour, a smile described as “flashing neon,” and his buttery sing-song voice, brought precisely the attention he was seeking. For better visibility, he wore a white tie and tails in large halls.

Adopting “Liberace” as his professional name, he billed himself as “Liberace—the most amazing piano virtuoso of the present day.”

Although he received continual offers to perform and record as a concert pianist, Liberace seemed to prefer the club atmosphere. However, he frequently accepted offers to play private parties such as those held by millionaire oilman J. Paul Getty at his Park Avenue apartment.

In light of his growing larger-than-life persona, Liberace decided to purchase a “priceless piano” to match his boundless talent. This was only the first of several extravagantly expensive pianos.

He purchased a rare, oversized, gold-leafed Blüthner Grand piano. In subsequent years, he bedazzled the audience with an array of ostentatious, custom-decorated pianos–some encrusted with rhinestones and mirrors.

In 1947, Liberace bought a luxurious home in North Hollywood and began performing at local clubs like the world-famous Ciro’s and The Mocambo He performed for film stars such as Rosalind Russell, Clark Gable, Gloria Swanson, and Shirley Temple.

But despite his success in the supper-club circuit (where he was often sandwiched between other acts), Liberace aspired to reach larger audiences as a headliner. He wanted to be a television and movie star.

To help him achieve this goal, Liberace assembled a publicity team and began looking for ways to make his shows more spectacular.

The Liberace Show

Despite his enthusiasm for television, Liberace was greatly disappointed with his early guest appearances. He appeared on The Kate Smith Hour (1950-1954), DuMont’s Cavalcade of Stars with Jackie Gleason (1949-1952), and later, The Jackie Gleason Show.

He was particularly disappointed with the amateurish camera work and his short appearance time. He knew that the only way to present himself on television with the same quality as his club performances was to get his own show.

After a short-lived LA-based television show (which was a smash hit, locally) and a run as a summer replacement show for The Dinah Shore Show, Liberace was given a 15-minute network television program aptly called, The Liberace Show. It debuted on July 1, 1952.

But it didn’t lead to a regular network series. Instead, in 1953, producer Duke Goldstone produced filmed versions of Liberace’s local shows performed before live audiences for syndication. He sold to scores of local stations.

The widespread exposure of the series made Liberace more popular and prosperous than ever. It earned him $7 million in the first two years.

Utilizing the television medium to the fullest, Liberace learned early on to cater to the tastes of the audience. He would joke and chat to the camera, as if performing in the viewers’ own living rooms.

He used dramatic lighting, “split image” effects, costume changes, and exaggerated hand movements. His hands were always studded with large, gaudy rings to create visual interest.

His television performances—which featured a broad range of musical selections from the Classics, Show Tunes, film melodies, Latin rhythms, ethnic songs, and Boogie-Woogie—were always exuberant. They had just the right touch of humor.

Liberace’s brother George often appeared as a guest violinist and/or orchestra director. His mother usually sat in the front row of the audience. His brother Rudy and sister Angelina were often mentioned to lend an air of “family.”

Liberace signed off each broadcast softly singing, “I’ll Be Seeing You”–which became his theme song.

The show was so popular (with his mostly female television-viewing audience). He drew over 30 million viewers at any given time and received 10,000 fan letters per week.

He’d become more than a star. He was a Pop phenomenon.

Vegas

After The Liberace Show went off the air in 1956, Liberace launched a number of successful tours of Europe. But his popularity began to wane in the US. It continued to do so for the next few years.

In 1963, Liberace returned to Las Vegas, becoming the primary performer at The Riviera Hotel. Upping the glitz and glamor, he took on the cognomen, “Mr. Showmanship.”

He referred to himself as “a one-man Disneyland.” His costumes became more exotic (mink, ostrich feathers, capes, huge diamond rings in the shape of tiny pianos).

His entrances and exits were more dramatic (he was chauffeured onstage in a Rolls-Royce). His choreography was far more complex (involving chorus girls, cars, and animals).

Among his guest performers was Barbra Streisand, the most notable new adult act he introduced. (Streisand owes much to Liberace for promoting her career.)

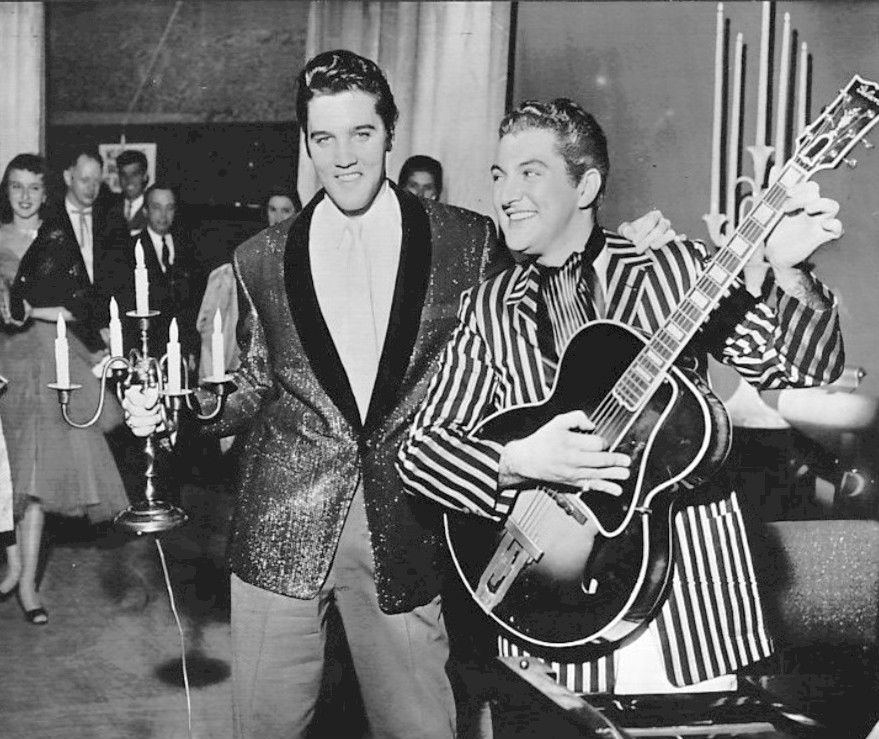

During the 1970s–1980s, Liberace’s live shows remained major box-office attractions at the Las Vegas Hilton and Lake Tahoe, where he earned an unprecedented $300,000 a week. By comparison, Elvis was paid a reported $7500 per week in 1956.

Television

Throughout his career, Liberace made a number of memorable appearances on popular television shows. These included Edward R. Murrow’s Person to Person (in 1956), The (Tennessee Ernie) Ford Show (in 1959), The Ed Sullivan Show (six times between 1964-1970), The Jack Benny Show (1954 and 1966), and The Red Skelton Show (1964, 1968 and 1969).

In 1960, he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in recognition of his contributions to the television industry.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Liberace made numerous appearances on “hip” television shows. These included Batman (1966), The Monkees (1967), and Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In (1968).

It also included Here’s Lucy (1970), Kojak (1978), and The Muppet Show (1978). On these, he performed renditions of “Concerto for the Birds,” “Misty,” “Five Foot Two,” and “Chopsticks.”

In 1978-1979, television specials were produced from Liberace’s live shows at the Las Vegas Hilton, which were broadcast on CBS.

Still remarkably popular in the 1980s, Liberace guest-starred on the phenomenally popular Saturday Night Live. He also appeared in the 1984 film Special People.

This was based on the true story of Diane Dupuy, who created a unique theater company called Famous PEOPLE Players. It consisted of developmentally challenged individuals. In 1985, he appeared on the debut episode of Wrestle Mania, as the guest timekeeper for the main event.

Films

He was never truly interested in becoming a recording artist. But the popularity that developed from Liberace’s syndicated television show created a clamor for his live performances to be made available on record.

To satisfy his fans’ demands, Liberace recorded nearly 70 discs (albums and singles) between 1947 and 1954.

Several recordings were released through Columbia Records including the album, Liberace by Candlelight. It sold over 400,000 copies by 1954. His most popular all-time single, “Ave Maria,” sold over 300,000 copies.

The End of a Brilliant Career

In August of 1985, Liberace was secretly diagnosed as HIV positive by his private physician in Las Vegas. Aside from Seymour Heller, his long-time manager, and a few family members and associates, Liberace kept his terminal illness a secret. He never sought a cure.

In August of 1986, during one of his last interviews, on Good Morning America, Liberace alluded to his failing health. He remarked, “How can you enjoy life if you don’t have your health?”

Liberace’s final stage performance was at New York City’s Radio City Music Hall on November 2, 1986. It was his 18th show of a 21-day tour. (The concert series grossed over $2.5 million for Liberace’s estate).

Liberace’s final television appearance took place on Christmas Day of that same year, on The Oprah Winfrey Show (which had actually been videotaped in Chicago a month earlier).

From January 23-27, 1987, Liberace was hospitalized for pneumonia at Palm Springs County Hospital. On the morning of February 4, 1987, Liberace died at his Palm Springs, California estate, at the age of 67. (His last meal, reportedly, was a bowl of Cream of Wheat.)

The Riverside County coroner determined that Liberace’s cause of death was cytomegalovirus pneumonia. This was a frequent cause of death in people with AIDS.

(Of note: Cary James Wyman, Liberace’s personal assistant and alleged lover of seven years, died of HIV complications in May of 1997, at the age of 34.)

References

britannica.com., “Liberace,” Liberace | Virtuoso, Entertainer, Showman | Britannica

biography.com., “Liberace,” Liberace – Movie, Piano & Death (biography.com)

theguardian.com., “Liberace: the 10 things you need to know,” https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2013/jun/07/liberace-10-things-to-know

Pyron, Darden Asbury, Liberace: An American Boy, https://archive.org/details/liberaceamerican00pyro

barbara-archives.info., “The Riviera Hotel (1963),” https://www.barbra-archives.info/riviera-hotel-las-vegas-1963-liberace

chicagotribune.com., “LIBERACE, 67, PIANIST TURNED ONE-MAN MUSICAL CIRCUS,” LIBERACE, 67, PIANIST TURNED ONE-MAN MUSICAL CIRCUS` (chicagotribune.com)

Lamb, Bill. “Biography of Liberace,” ThoughtCo, Aug. 18, 2021, thoughtco.com/liberace-biography-4151847.

reviewjournal.com., “Walter Liberace,” https://www.reviewjournal.com/news/walter-liberace/