By the early 1950s, Harper’s Bazaar was well into what Christian Dior would refer to as “the golden age” of fashion. It was an era that Dior himself helped jolt into being with the unveiling, in February 1947, of his “New Look.” “Swirling skirts. Pleats and pleats. Dior makes a skirt 45 yards wide,” Bazaar raved in the October 1947 issue, marveling at Dior’s quasi- libertine use of material, coming as it did on the heels of wartime fabric rationing. It was a boon for couture, as Paris reclaimed its place as the seat of high fashion; the houses of Balenciaga, Balmain, and Fath were all flourishing. And more designers were following in the footsteps of Chanel and Schiaparelli, and branching out into fragrances, boutiques, and licensing deals.

Back in the United States, the country was awash in a wave of prosperity. But in the wake of World War II, a lot of the old mythologies about what to desire and how to live were breaking down. There was also a burgeoning interest in the existentialist writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus, and the American Beats like Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs. Nuclear weapons were being developed, the Cold War was brewing, a counterculture was forming, and McCarthyism was in full force.

Bazaar rebounded from the uncertainty of the war years with a vengeance. Carmel Snow’s cool eminence, Diana Vreeland’s wild imagination, and Alexey Brodovitch’s creative genius are all by now the stuff of lore, and the magazine they made together was once again the definition of fashion. But they didn’t do it alone.

Richard Avedon was fresh out of the Merchant Marine when he came to Bazaar in 1944. When he had enlisted, his father, Jack, gave him a Rolleiflex camera as a going-away present, so he applied for a job in the photography department and was assigned to a post in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where he fulfilled his service by taking pictures of events on the base, shipwrecks, and autopsies.

The Avedons once owned a department store on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue but had lost it during the Depression. Because of Jack’s job as a clothing buyer for retailers and Avedon’s mother’s passion for culture (she had wanted to be an artist), there were occasionally copies of Bazaar around the house. Avedon later recalled a time when the family’s financial fortunes took a turn for the worse, and they were forced to move into a smaller apartment, where he slept in a dining alcove, with pictures by Martin Munkacsi that he’d torn out of Bazaar taped to the wall. “Harper’s Bazaar had a glow,” Avedon told the magazine in 1994. “It was a happy combination of the things my parents valued in American life.”

Avedon became interested in photography at a young age. One of his earliest subjects, and in many ways his original muse, was his sister, Louise, a dark-haired beauty with big, soulful eyes that masked her inner torment. “My mother used to tell her, ‘With skin like that and eyes like that you don’t have to speak,’ ” Avedon said. “She was so lovely and so shy no one recognized the pain there. She entered a mental institution in her 20s and died there when she was 42. She was damaged by her beauty. I believe beauty can be as isolating as genius, but without its rewards.”

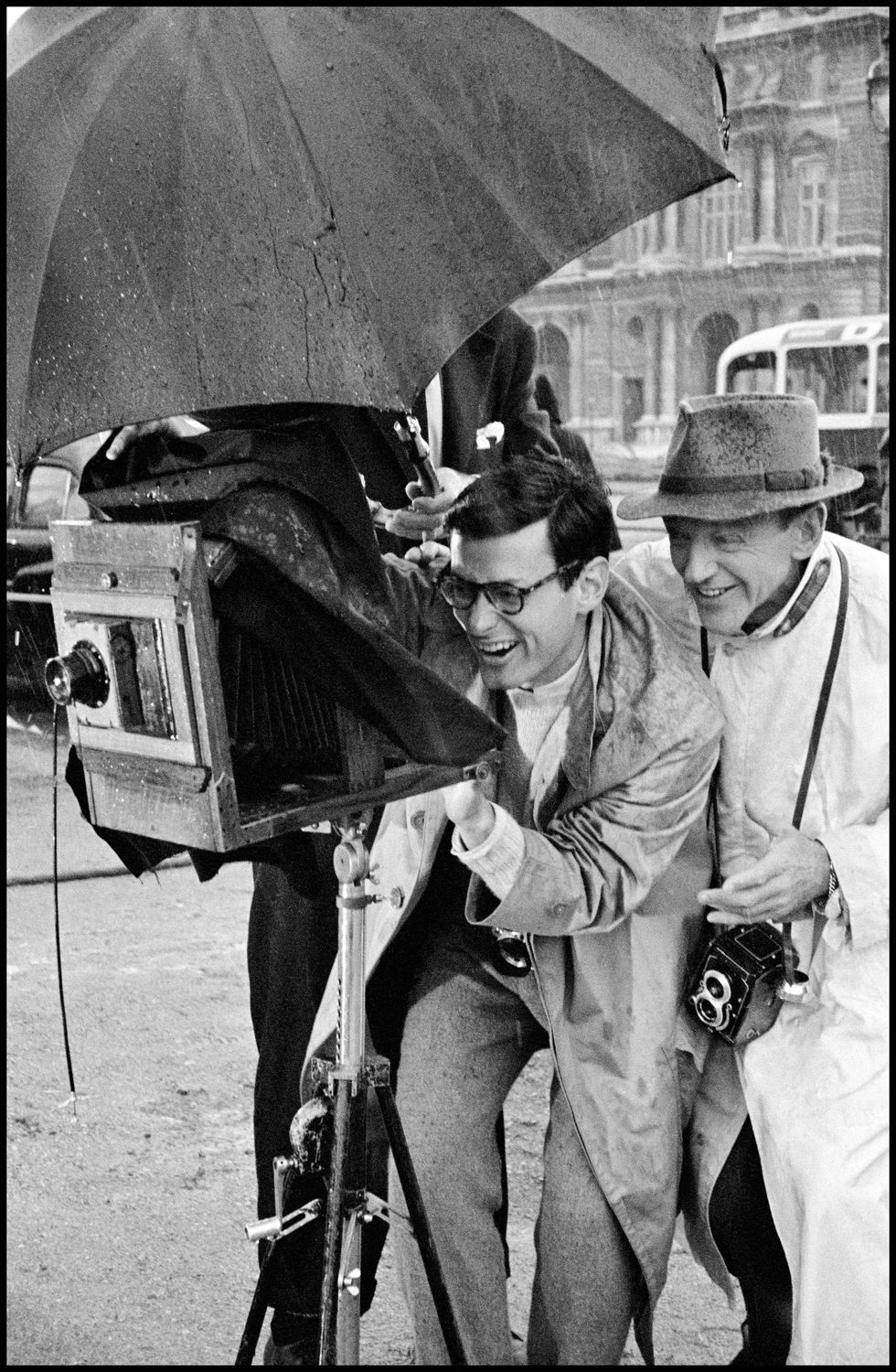

After leaving the Merchant Marine, Avedon resolved to get a meeting with Brodovitch. He took classes that Brodovitch taught at the New School and made, by his count, at least 14 appointments with him, all of which were canceled. But Avedon was dogged: “I knew where he lived, and I left my work at his house.” When Brodovitch finally agreed to a meeting, he quickly zeroed in on a picture Avedon had shot during his time in the Merchant Marine of a set of twins, with one rendered clearly in the foreground and the other out of focus in the back. “He wanted me to apply that experiment to fashion photography,” Avedon said.

Avedon was 21 when he landed his first assignment for Bazaar: a shoot for a special supplement to the magazine’s November 1944 issue called Junior Bazaar, which offered teenage girls advice on clothes, makeup, and coming-of-age topics. “I want to be a fireman when I grow up,” he joked in the note that ran in the “Editor’s Guest Book” section of the issue. “Now he is off to Mexico,” the note continued, “with a Rolleiflex over his shoulder and a dozen Bazaar dresses on his lap.”

Avedon’s photographs soon set the visual tone for the magazine. The women in his pictures weren’t statues or seraphs—they were living beings who danced and leaped and longed and moved in blurs. There was a searching in his images, an ephemeral quality.

He was drawn to subjects who had some road under their feet. Two of Avedon’s favorite models at the time were Dorian Leigh, a mother of two in her late 20s who lied about her age to get work; and a statuesque brunette from Queens named Dorothy Virginia Margaret Juba, who’d rechristened herself “Dovima” after the name of an imaginary friend she conjured when sick with rheumatic fever as a child. Later, Leigh’s youngest sister, the willowy redhead Suzy Parker, whom Avedon initially deemed too conventionally pretty, would come alive in front of his camera to become one of the most successful models of the 1950s. Parker also made forays into acting, appearing in a cameo in the 1957 film Funny Face, starring Audrey Hepburn.Incidentally, the movie fictionalized Avedon’s relationship with his first wife, the model Doe Avedon, played by Hepburn, another subject the photographer would shoot for a range of Bazaar covers and fashion sessions.

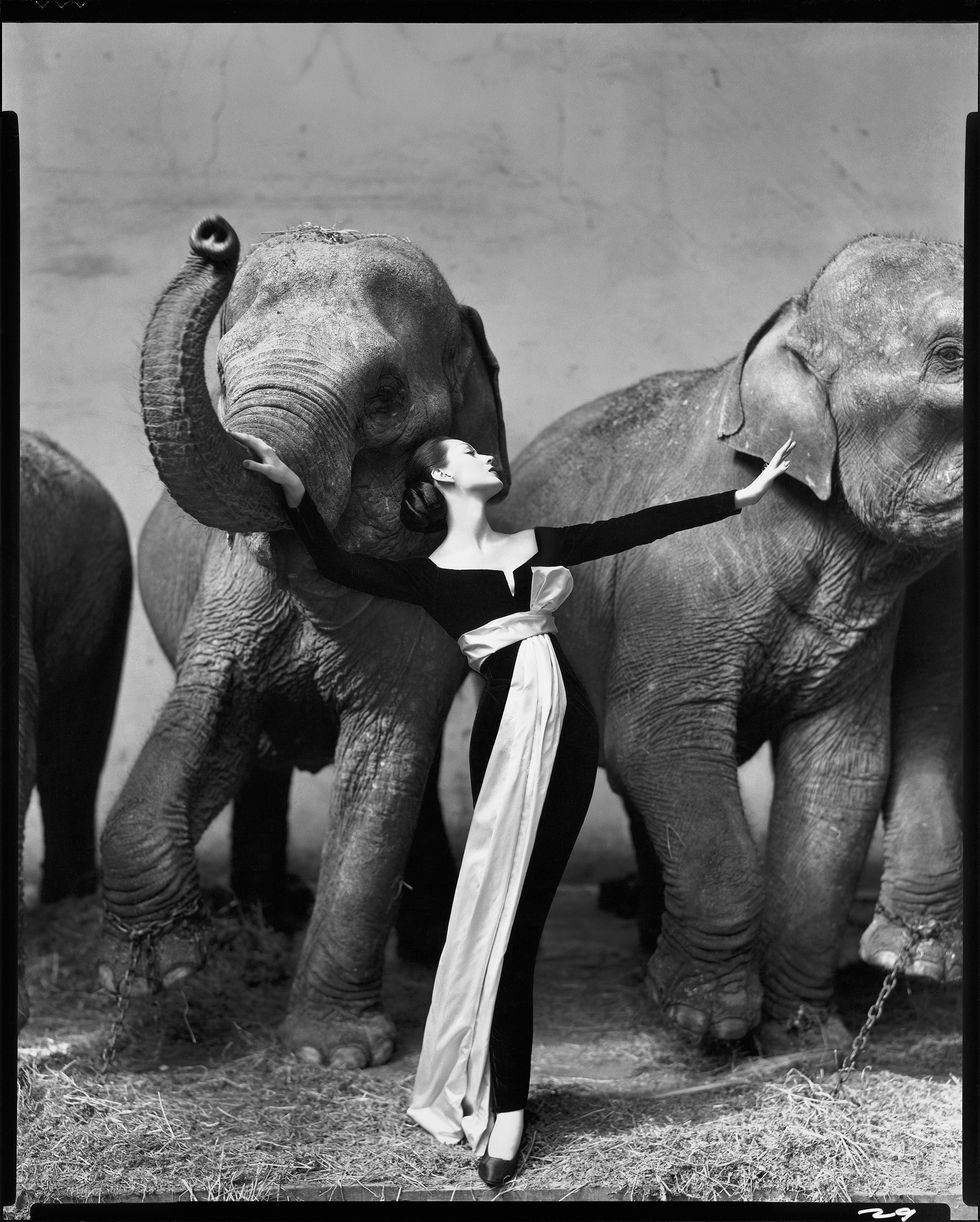

It was Dovima, though, who featured in what is often considered the most indelible fashion picture ever to grace the pages of Bazaar. The image, part of a full session shot by Avedon at the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris on a warm day in August 1955, depicts Dovima artfully posed between two elephants in a Dior gown. Today, “Dovima with elephants” endures as an emblem of the power, beauty, and mythology of fashion, and is in the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art. But despite the image’s place in the annals of fashion photography, Avedon remarked, “The sash isn’t right,” while hanging the photograph for an exhibition three years before his death, in 2004. “It should have echoed the outside leg of the elephant to Dovima’s right.”

Truman Streckfus Persons first arrived in New York in 1933. Born in New Orleans to a salesman and his teenage bride, Truman was dispatched to live with family in Monroeville, Alabama, before his parents divorced when he was seven. His mother later remarried and was living in Manhattan, so she sent for her son. Her new husband, a well-off Cuban-born textile broker named Joseph Capote, adopted him, which is how he came to be known as Truman Capote. In New York, the young Truman attended an Upper West Side private school before deciding, at age 11, to become a writer.

Capote’s debut in Bazaar came a little less than a year after Avedon’s, in the fall of 1945. The magazine’s fiction editor, Mary Louise Aswell, spotted a story Capote, then just 20, had written called “Miriam,” in Mademoiselle (where Bazaar’s combustible former literary editor, George Davis, was overseeing the fiction department). Aswell tracked down Capote and, after reviewing some of his manuscripts, decided to publish a story called “A Tree of Night,” about a 19-year-old college student named Kay who encounters a mysterious couple on a train. “As Kay watched, the man’s face seemed to change form and recede before her like a moon-shaped rock sliding downward under a surface of water,” Capote wrote. “A warm laziness relaxed her. She was dimly conscious of it when the woman took away her purse, and when she gently pulled the raincoat like a shroud above her head.” “A Tree of Night” ran in the October 1945 issue and would serve as a cornerstone of Capote’s first collection.

Capote’s presence in Bazaar helped thrust the magazine into the center of the postwar social swirl. He was unabashed in his embrace of society life, jubilantly gliding through the Stork Club and El Morocco with glamorous women like Gloria Vanderbilt and Oona O’Neill on his arm. Capote didn’t take it all too seriously: He was reputed to be the originator of a game called International Daisy Chain, a version of Six Degrees of Separation that involved connecting, by the least number of steps possible, socialites and celebrities thought to have been sexually involved. Capote’s instincts about the culture he had come to inhabit were notably prescient. “Nowadays, when not anyone is much of a mystery, when indeed the effort everywhere is to publicize celebrated figures as having personalities interchangeable with one’s drearier neighbors, Garbo remains, after eleven years of professional retirement, an unconquerable legend,” he wrote of his friend, the notoriously reclusive actress Greta Garbo, in Bazaar’s April 1952 issue. “Because she is beautiful; and it is beauty of depth, of interest: to watch her face is like contemplating a masterwork.”

Capote’s fascination with wealth, fame, glamour, conspiracy, secrecy, and the gleam of high society and movie stars—all of which found their way into his other writing for Bazaar—was apparent from the start. With it came a foreboding sense of the tragic that never seemed far beneath the surface. He could be tart, petulant, self-pitying, and even cruel. Robert Linscott, Capote’s editor at Random House, once famously described the writer as shrouded in the “stigmata” of his own brilliance. But his volatility at times seemed more deeply embedded. When Capote was a child, his mother readily admitted she felt ill-suited to motherhood; years later, after Joe Capote’s conviction for embezzlement, she took her own life by consuming a handful of sleeping pills. In Capote’s life, as in his work, things often didn’t end well.

The friendship that developed between Capote and Avedon was of mutual admiration—with a degree of distance. For most of the 1950s they ran on parallel tracks, each of his own devising. To say Avedon changed fashion photography is by now a truism, and in Capote Bazaar helped launch one of the most prominent—and polarizing—literary icons of the mid-20th century. But their work for the magazine illuminated something essential about what Avedon would later characterize as the “performance” of living—or what Capote, in discussing fiction, once referred to as “the truth inside the lie.” In the artifice of fashion, Avedon said, he found “a kind of grace without the pressure of belief.” In a world that was very much about keeping up appearances, he and Capote also found art and salvation.

In 1959, Avedon compiled a volume of portraits entitled Observations, for which Capote wrote the text. The book featured pictures of royalty, heiresses, and doyennes Avedon had photographed for Bazaar over the years—women Capote referred to as the “swans” of society. In it, Capote recalled meeting Avedon one winter Sunday at the photographer’s studio to go over the images for the book. “Avedon was in his stocking-feet wading through a shining surf of faces, a few laughing and fairly afire with fun and devil-may-care, others straining to communicate the thunder of their interior selves, their art, their inhuman handsomeness, or faces plainly mankindish, or forsaken, or insane: a surfeit of countenances that collided with one’s vision and rather stunned it,” Capote wrote. “ Sometimes I think all my pictures are just pictures of me,” Avedon told him. “My concern is, how would you say, well, the human predicament; only what I consider the human predicament may be simply my own.”