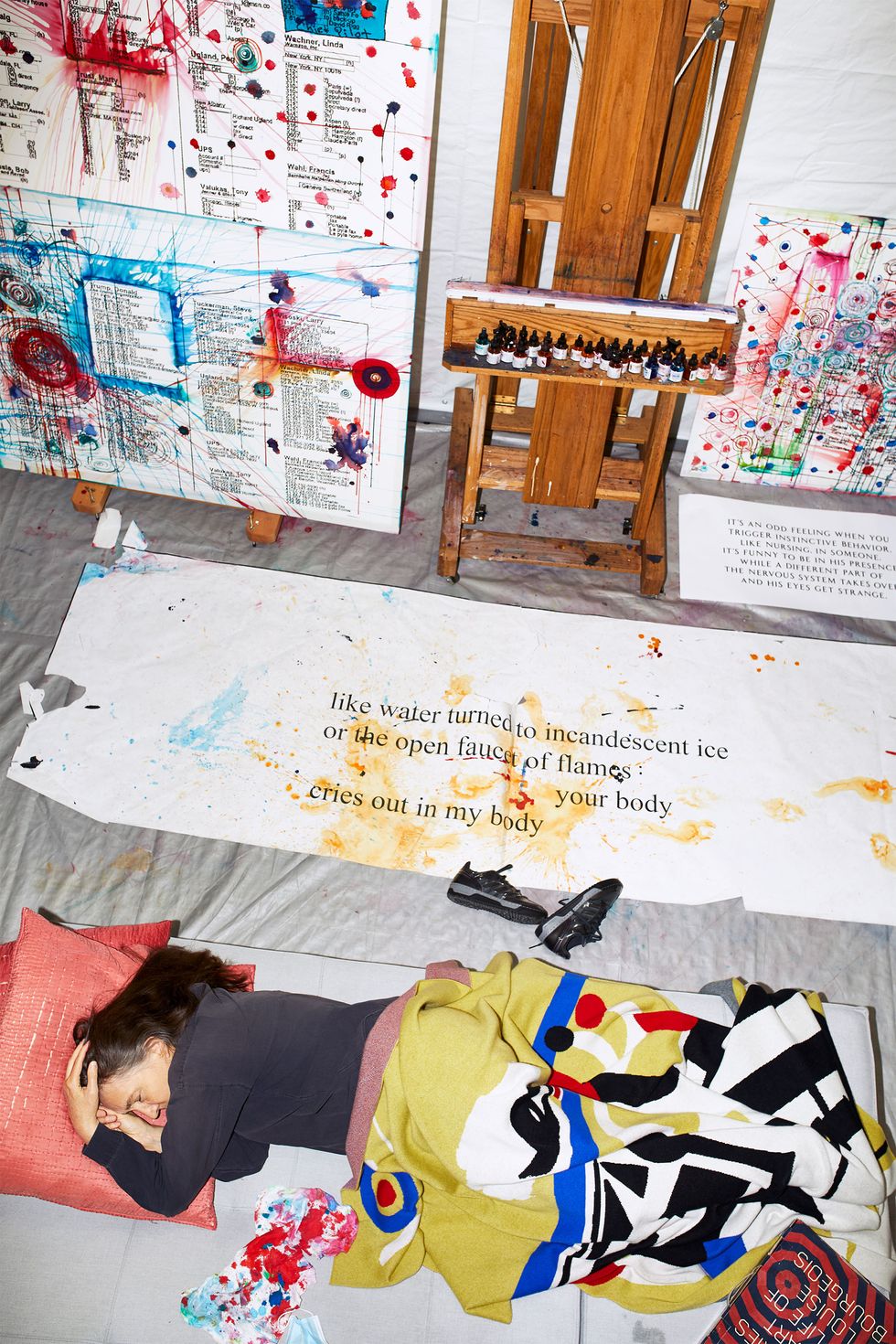

Back in February, before the world warped into a pandemic thriller, before the killing of George Floyd ignited a movement for racial justice, before an uninsignia’d military-style police force was dispatched to quell protesters in the streets of American cities, Jenny Holzer stood in a small, windowless side room in her otherwise bright Brooklyn studio overlooking the East River. Transparent plastic sheets lined the floors; blood-red watercolors in progress leaned against the walls. I told her it looked a bit like a crime scene. “Or an abattoir,” she said.

The watercolors began, Holzer explained, with reproduced enlargements of declassified government documents, to which she added paint in carefully modulated drips, sometimes producing loose, flowing skeins, at other points short, intense dabs and oozing puddles of crimson. This particular series took serial sex offender Jeffrey Epstein’s “little black book” as its base. “What a hateful man,” she told me later. “The president wished Ghislaine Maxwell well relatively recently,” she said of Epstein’s alleged enabler, a reputed Trump associate. “Twice.” Renowned for works that are chock-full of content and often address the most pressing issues of the day, Holzer has long adopted words as her medium. The pithy phrases from her late-’70s “Truisms” series, like your oldest fears are the worst ones and lack of charisma can be fatal, which have appeared on baseball caps, stone benches, and billboards in the years since, were often ambiguous or contradictory. But some, like abuse of power comes as no surprise, do seem to align with Holzer’s greater worldview as an artist who continuously addresses new forms of social and political malfeasance.

That last expression in particular has in recent years been adopted as a clarion call by those working toward progressive ends: In November 2014, pictures of the phrase in various instantiations went viral in the immediate aftermath of a grand jury’s decision not to indict Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown Jr.; the group We Are Not Surprised, dedicated to combating sexual harassment in the art world, also took its name from the “Truisms” (with Holzer’s endorsement).

Holzer, who usually spends more than half her time on the road, has been isolating since March at a farm in upstate New York with her husband, the artist Mike Glier; her daughter, Lili; her son-in-law, Maciek Kobielski (who photographed this story); and her two young grandsons, Cyprien and Henry.

When we caught up by phone in July, she was still at work on the Epstein watercolors, her painting practice—what she calls her “one-woman watercolor society”—reconstituted in a former corn crib turned studio. “Drizzling has been a good displacement activity,” she told me.

Our age of quarantine has been a busy time for Holzer. In late May, she sent trucks bearing an array of new texts, titled EXPOSE, around the streets of New York and Washington, D.C.: the people perish, unnecessary death can’t be policy , and covid-19 president were among the phrases illuminating LED signs on the backs and sides of each one in pulses and flashes of fiery hue. Having organized numerous such actions with trucks over the past few years, Holzer says they have the process down to a science. “We can get trucks out on the street fast,” she explained. “The truckers are ready at the drop of a hat. The hard part is picking, writing, and sequencing content, and then animating the text. We might offer a collection of fact, poetry, and blurting. We choose truck routes carefully in order to park near or drive by landmarks so the maximum number of people can watch.”

In early June, a group that included Holzer projected a transcript of the recordings of Floyd’s final words before his death at the hands of Minneapolis police onto a building in Brooklyn near a major thoroughfare, the slowly scrolling text visible to residents, pedestrians, and large swaths of car traffic. Titled IN MEMORIAM, the projection paid testament to Floyd’s last moments, but it also served as a rallying cry, including a list of the names of 115 Black people whose lives have been taken by police or as the result of racial violence.

IN MEMORIAM shares a guerrilla quality with Holzer’s earliest work, which included “Truisms” posters she wheat-pasted around downtown Manhattan by dark of night. Her light projections usually require months of meticulous planning, but with the aid of a lightweight digital projector and a team of collaborators, this one came together in a little more than two weeks after Floyd’s death. “We projected quickly because we thought Floyd’s words should appear fast,” she said. “Our group pulled the projections off at warp speed.”

This past July, Holzer launched a new series of vibrantly animated displays in Times Square, where she has presented several public artworks since the 1980s. At various times, they took over big groups of the massive digital billboards that tower above 42nd Street, with the enormous word protect segueing into nurses and doctors—a kind of digital version of the 7 p.m. ovations for front-line and essential workers that lit up otherwise deserted-looking cities after stay-at-home orders began to come down in the spring.

The animated texts appeared slightly earlier in the pandemic’s course on Holzer’s Instagram. Though fake Jenny Holzer accounts have circulated on Twitter for years—some featuring real texts from Holzer’s work, others proffering their own brand of Holzer-Wisdom: “Jenny Holzer, Mom”; “Jenny Holzer, Cat”—she has largely avoided social media until recently. Instagram sometimes serves as a testing ground for particular meshings of form and content. “It’s interesting to see what’s a complete fail and what seems to catch people,” Holzer explained. “I’m not sure I’ll keep doing it. But the practice has been handy.”

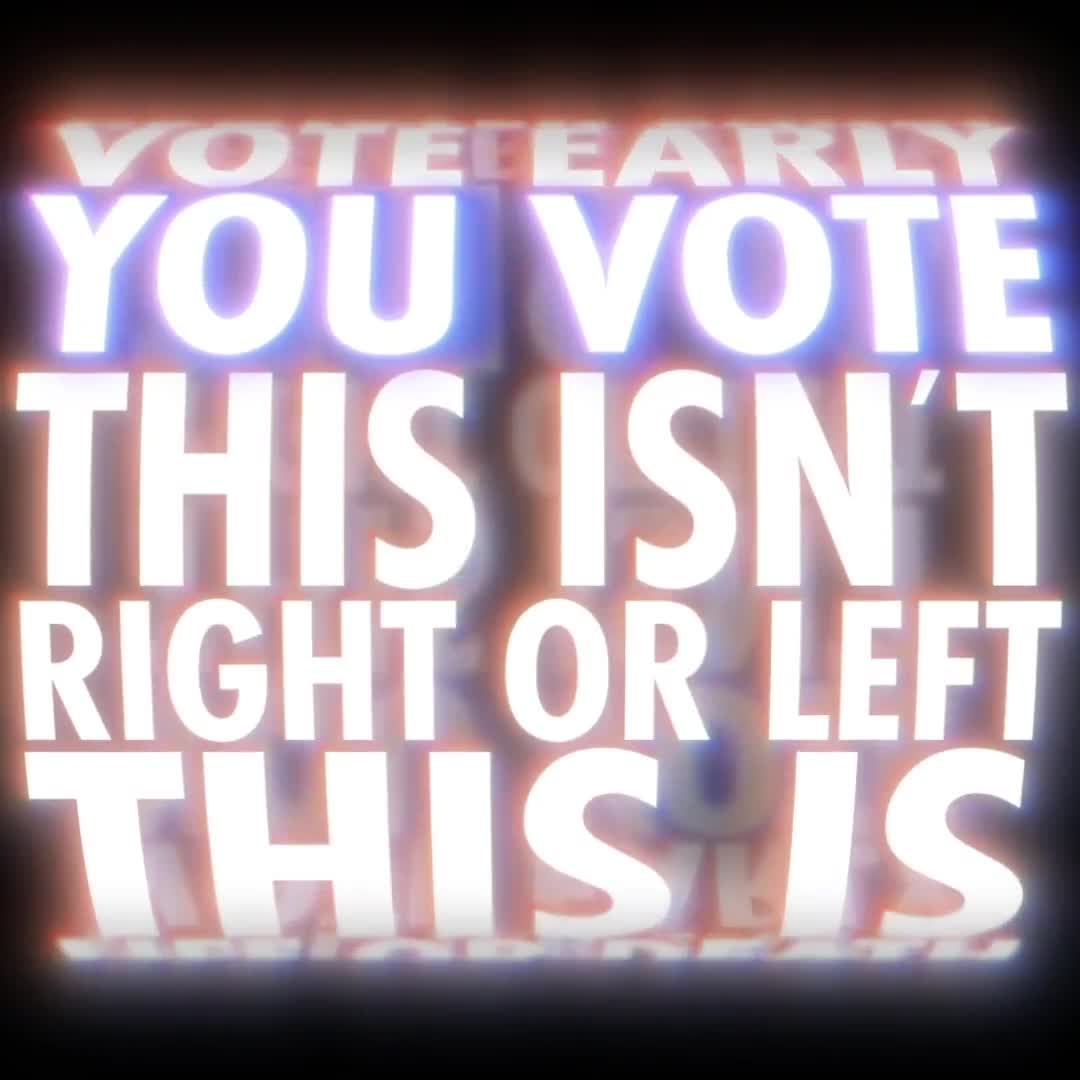

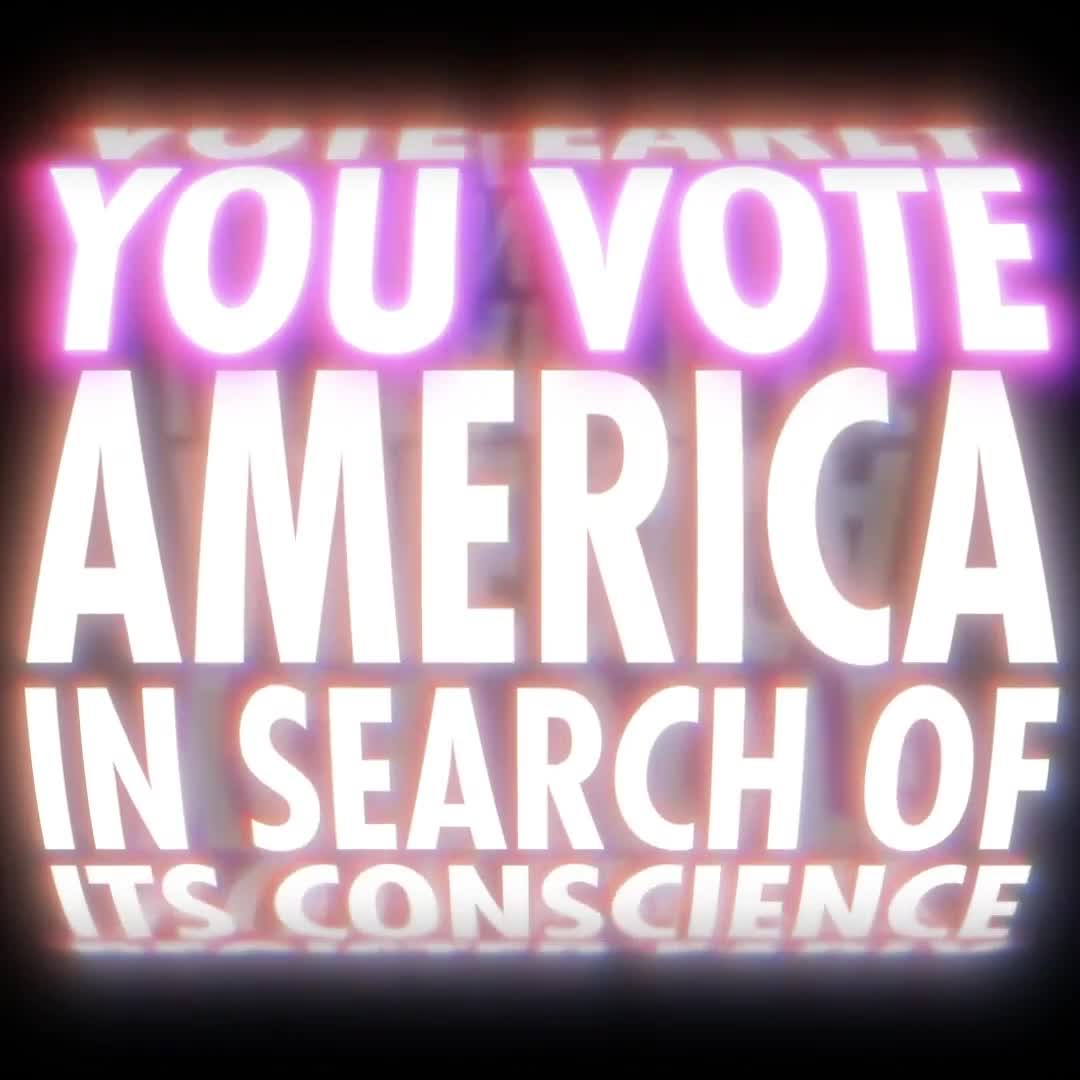

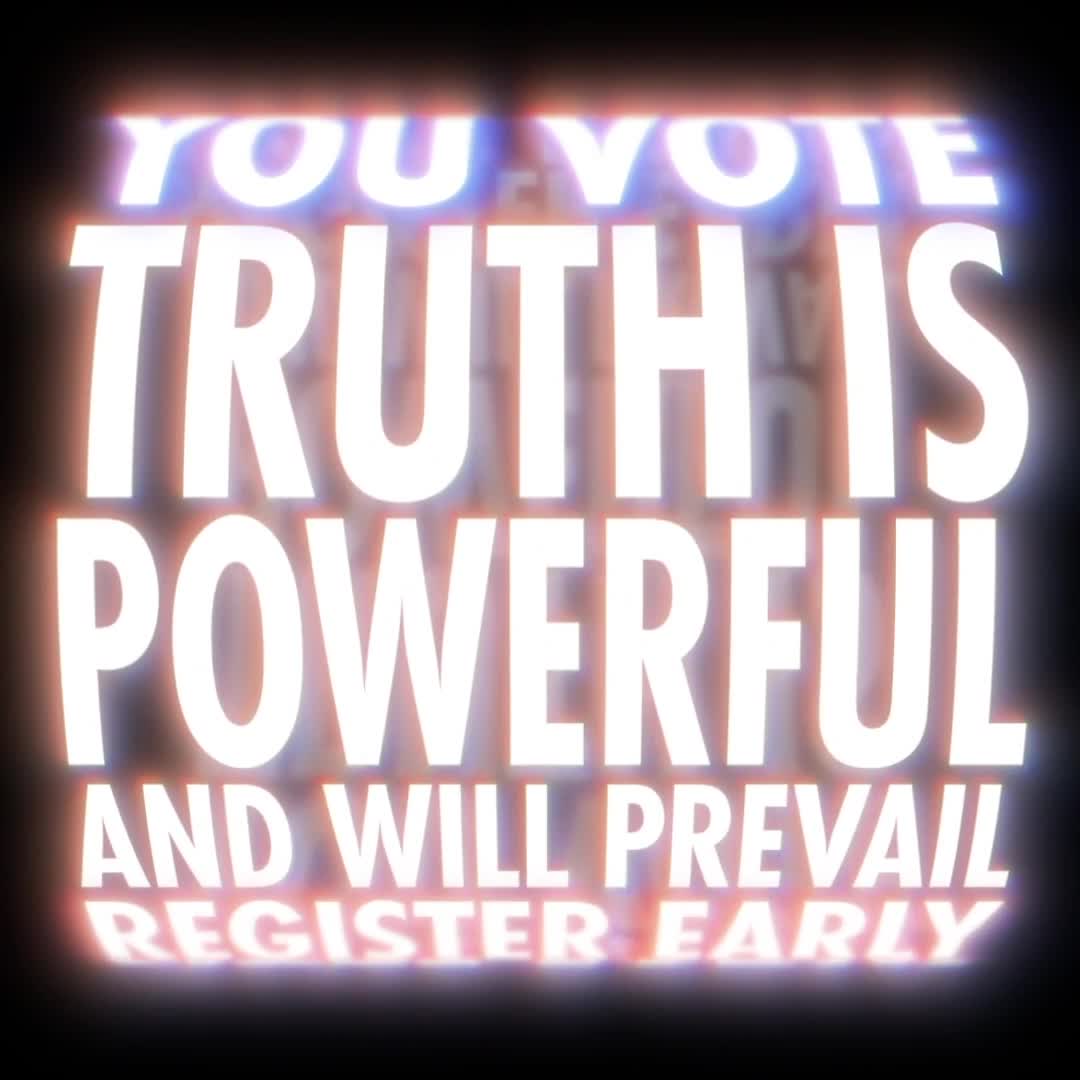

When we spoke, Holzer was designing a bandana for Artists Band Together, an initiative organized by a collective largely made up of women activists, writers, and arts professionals. Bandanas created by a range of well-known and emerging artists will be sold to benefit the organizations Woke Vote, Mijente, and Rise, each of which seeks to expand voter registration and get out the vote, with a particular focus on young Black, Latinx, and Chicanx voters. Holzer was also planning a series of new actions, entitled YOU VOTE, in advance of the November presidential election geared to both encouraging voter registration and combatting voter suppression. “We’ll highlight issues that are germane, that are especially alive at election time,” she said. “We’re trying to learn enough and be of some small utility.”

Holzer’s work has long sounded the alarm about political crises: Over the years, projects have examined the U.S. government’s use of torture in the War on Terror; the deployment of rape as a weapon in the Bosnian War; and the plight of Syrian refugees, among other disturbing states of affairs. Her pieces addressing the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and ’90s remain among the most searing of artistic responses to that pandemic. I asked Holzer what she makes of the eerie callbacks to that time some have experienced this year, seeing National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony Fauci, a key figure during the AIDS epidemic, back in the news as a deadly disease spreads at breakneck speed. “Reagan made the AIDS epidemic worse. More people suffered and died than necessary,” Holzer said. “Sound familiar?”

Drawing on years of experience exposing and countering the abuse of power, Holzer resists the paralysis into which it would be so easy to slip during this current moment of Covid-19, racial injustice, inequality, and political and economic strife, instead engaging all of these emergencies at once and on multiple fronts. “I do dire even when things are good, so now that times are dire, I fit,” she told me. “It’s not a time to be stumped.”

YOU VOTE 2020 videos: © 2020 Jenny Holzer, member Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY; Animation: Seth Brau

Special thanks to Haidee Findlay-Levin, Alanna Gedgaudas, Lili Kobielski, Ariel Rosenblum, Erik Sumption, and Seth Zucker