“If I die today, remember me like John Lennon,” Lil’ Wayne once rapped. Just a few weeks ago, on his new album, King’s Disease, Nas lamented the pressures put on veteran artists, concluding that “the McCartneys live past the Lennons, but Lennon's the hardest.”

Beatle shout-outs have long been a staple in hip-hop (Rae Sremmurd hit Number One with “Black Beatles” in 2016), as they are throughout our culture, in books and movies and daily life. But how exactly do we remember John Lennon? In recent years, the legacy of this revered icon has gotten more complicated, and more problematic. This season will be presenting us with multiple opportunities to assess his current reputation: October 9 would have been his 80th birthday, with a tragic twin anniversary just a few months away, as this December 8 will mark forty years since Lennon’s murder.

The dates are being commemorated by a number of new projects: a new box set called Gimme Some Truth, The Ultimate Mixes, on which 36 of his best-known songs have been completely remixed from scratch; a BBC radio special hosted by his son Sean and an upcoming BBC TV documentary; tribute albums and shows; and multiple books, mostly looking at the final years of his life. Yet it seems that in recent years, Lennon’s standing in the rock & roll stratosphere has started to drop off.

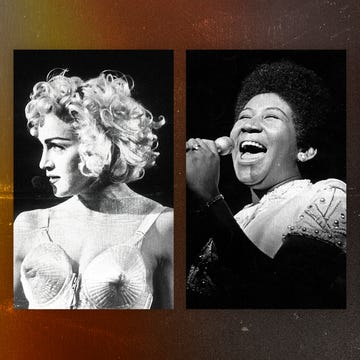

Paul McCartney continues to tour, heroically and tirelessly, still filling stadiums and thrilling multiple generations (until our current circumstances struck) and making well received new music; there are rumors that an album recorded during lockdown will be released by the end of the year. Meanwhile, George Harrison’s mystic spirituality has only enhanced his favored spot as the undiscovered Beatle, the hipster’s choice; “Here Comes the Sun” is far and away the band’s most streamed song on Spotify, and a 2018 NBC headline proclaimed “How the quietest Beatle became the most popular one of all.”

For one highly unscientific example, a few months ago on my SiriusXM radio show, we posted an impromptu Twitter poll asking our listeners to name their favorite Beatle. Paul and George were neck-and-neck leaders, with John trailing by a distance. (Ringo Starr, eternally beloved and underrated, picked up his usual handful of supporters.)

A more substantial data point is Rolling Stone’s recently revised list of the “500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” The magazine greatly expanded the number and breadth of voters since the last time they created this ranking in 2012. The Beatles overall took something of a hit: Eight years ago, they held four of the top ten spots, but now, only Abbey Road—which has become the preferred choice for Gen Z listeners—came in that high, placing at No. 7. Rubber Soul plummeted from No. 5 to 35.

Lennon’s solo recordings, while still ranking the highest of the solo Beatles’ catalogues, also dropped dramatically. Plastic Ono Band fell from 23 to 85, and Imagine from 80 all the way to 223. Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, in contrast, jumped from 433 to 368, while McCartney was essentially a wash: Band on the Run, which had been in the 418 slot, fell off the list but was replaced by the more indie-friendly Ram, coming in at 450.

So why does John Lennon, for decades one of the world’s most beloved figures, seem to be coming under increased scrutiny, and getting a more critical look, from younger generations? Maybe it’s the shorthand associations we assign to his tragically abbreviated life. First—and there’s no way around it—is the mixed blessing of “Imagine.” One of the world’s best loved anthems, it has also become a bit of a punch line, as proven by the savage internet takedown of the “Imagine” cover posted by Gal Gadot, and featuring such celebrities as Natalie Portman, Will Ferrell, and Jimmy Fallon, during the early days of the Coronavirus. “In a country where only the privileged seem to have access to adequate testing,” wrote Vice, “the last thing we want to watch is a remix of rich people quarantining in their mansions telling us to ‘imagine’ a better world.”

It’s the song, more than any other, that has defined Lennon’s legacy (in another Rolling Stone list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time,” it placed higher than any Beatle track), and it is increasingly perceived as a well-intentioned, hippie-dippy dream. His radical intentions—calling on us to imagine “no religion” and “no possessions”—have largely been glossed over in favor of a naïve, feel-good message of unity.

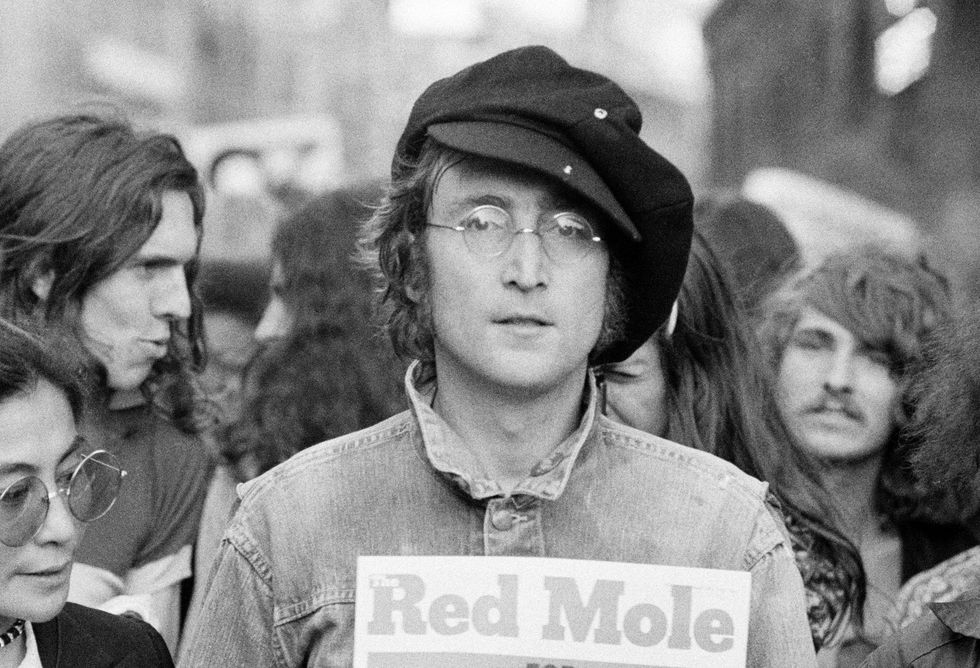

For listeners born after Lennon’s death, the most prominent images they have of him are his role as “the political Beatle” and his devotion to Yoko Ono, who remains a polarizing figure. These are certainly noble traits, but it’s also easy to see that they’re less appealing to millennials—too serious to be fun, too earnest to be cool. His caustic wit and fearless speech (the kind that got him into trouble when he said that the Beatles were “more popular than Jesus”) also plays differently in 2020.

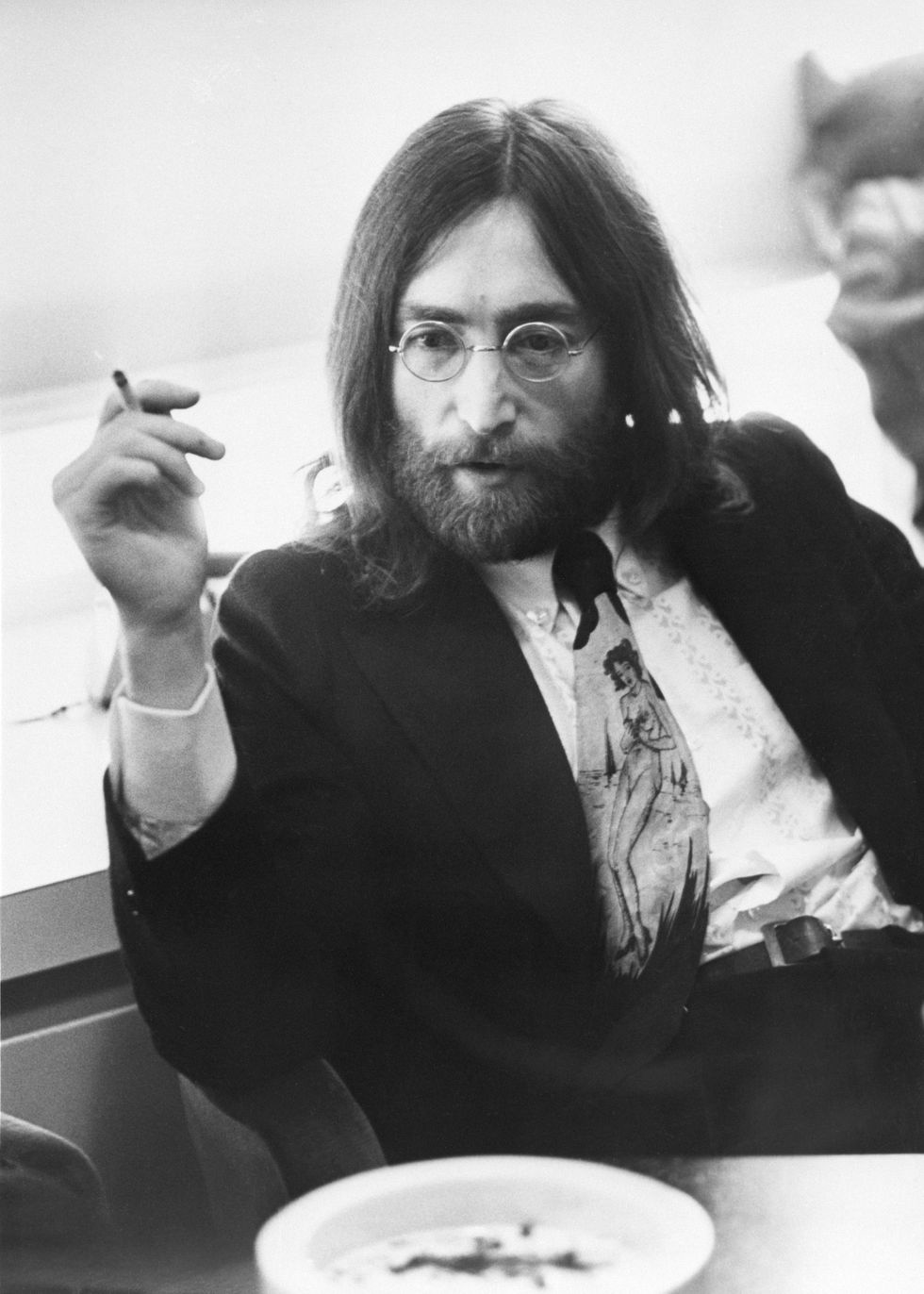

Lennon was open about being a neglectful, even abusive husband and father—“I used to be cruel to my woman/I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loved,” he sang on “Getting Better”—and he was an obnoxious drunk during his “Lost Weekend” separation from Ono in the mid-’70s. There's no excuse for this behavior, no matter how much he addressed and apologized for it, and it's certainly regarded differently in a post-#MeToo world. During his life, he admitted his sometimes toxic bravado was a defense mechanism. “I spent the whole of my childhood walking in complete fear, but with the toughest-looking face you’ve ever seen," he once said.

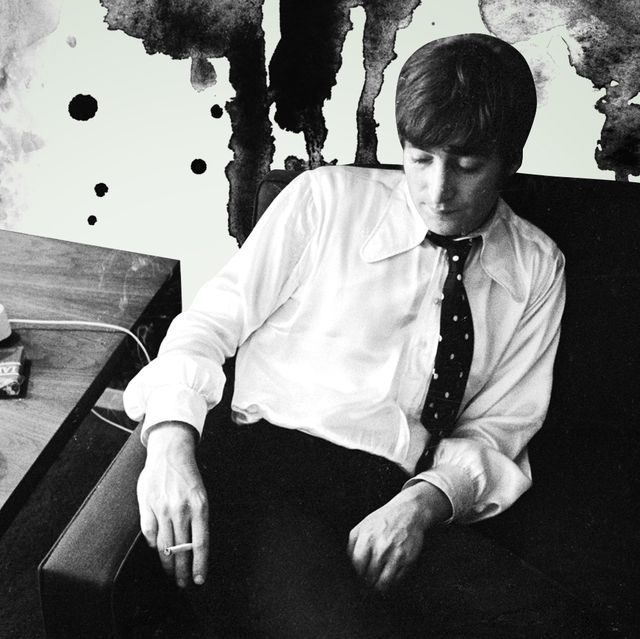

But the irony is, no matter how rightly critical we are of him today, Lennon's influence remains a powerful presence in pop culture and music. Among his greatest contributions (along with being one of rock’s greatest singers—despite always hating the sound of his own voice) was his leap into personal and confessional songwriting. Following the first wave of Beatlemania, Lennon turned to a new kind of self-reflection in his lyrics, with songs like “Help!” and “In My Life” and “Nowhere Man.” Pop songs had obviously long addressed heartbreak, but no one had ever written about isolation, fear, and uncertainty in such direct terms on a record before.

“I’ve never enjoyed writing third-person songs,” he once said. “Most of my best songs are in the first person. I like to write about me.” Elsewhere, he said that “I don’t know when exactly it started, like ‘I’m A Loser’ or ‘Hide Your Love Away,’ or those kinds of things. Instead of projecting myself into a situation, I would just try to express what I felt about myself.”

Pop in 2020 has become a direct descendent of this impulse. Simple, upbeat dance songs are steadily being overtaken by something more serious and introspective. From The Weeknd to Ariana Grande to BTS, teen idols have increasingly been writing and singing about mental and emotional health, anxiety, and loss. (A 2018 study at the University of California Irvine examined hundreds of thousands of English-language pop songs and confirmed that expressions of sadness were steadily on the rise, while research by the Quartz website confirms that use of the words “depression” and “anxiety” in lyrics is growing steadily.)

“Looking back on it, I think songs like ‘I’m A Loser’ and ‘Nowhere Man’ were John’s cries for help,” Paul McCartney once said. “You didn’t really think about it at the time, it’s only later you think, God! I think it was pretty brave of John.”

Lennon turned his own life into his subject matter—as literally as “The Ballad of John and Yoko”—writing about everything from his withdrawal from heroin (“Cold Turkey”) to his years as a househusband following Sean’s birth (“Watching the Wheels”). His mother who abandoned him, his wife, his children all became characters in his songs, in unprecedented ways that rappers like Eminem, Kanye West, and Drake continue to develop.

And, of course, there’s Lennon’s activism. “Revolution,” “Give Peace a Chance,” “Power to the People,” and songs about the riots at Attica State Prison or the harassment of revolutionary leaders like Angela Davis and John Sinclair—as tired as it is to extol the protest songs of generations past, there’s no one in rock’s canon closer to the action in our streets today. For what it's worth, he even recognized his own chauvinism, singing on "Power to the People," "I gotta ask you comrades and brothers/How do you treat your own woman back home?"

Ultimately, one of the terrible effects of John Lennon’s murder is that it turned him into exactly what he never wanted to be—a martyr. The real reason he seems too distant, too unapproachable, for listeners today is that they likely see him first as a victim, a symbol, not a complex and flawed and unfinished individual. He even spoke about this trap himself, once describing the danger of turning Gandhi and Martin Luther King into “The Leader and the Saint and the Holy Man Who Does No Wrong.”

“Nobody likes saints alive,” he said. “They like them dead. And we don’t intend to be dead saints. We’d rather be living freaks."