What's the News: Computers are hot. Too hot, really, for their own good---not only can laptops burn users' thighs, but big clusters of servers require constant air conditioning, leading cloud-computing companies to consider situating them in places like Iceland to save on costs. On the other hand, for part of the year in a good chunk of the globe, humans are cold. Analysts at Microsoft Research wondered whether they couldn't somehow make these two things match up. The Concept:

Server farms don't produce enough heat, unfortunately, for it to be efficiently recycled into electricity. But their exhaust falls into a temperature range---104-122 degrees F---that's perfect for human needs like heating.

In a new paper, the Microsoft team suggest that by swapping a building's furnace for a box of servers belonging to a cloud-computing firm, owners of apartment complexes, offices, campuses, and homes could circulate that heat using the existing duct system, saving money on equipment and possibly receiving free upgrades to faster internet service, since the servers will need the connection to be part of the cloud.

By putting servers in buildings, cloud-computing companies would save the money and energy used to cool the servers and could, by providing the servers at a price much lower than that of a furnace and then charging a monthly rate for heating, get a new source of revenue.

The Details:

As an exercise, the team looked into the feasibility of putting such "data furnaces" into private homes, including when and where they could be used and whether they would be cost efficient.

Obviously, local weather patterns would determine how much of the year such a system would be useful (the servers would probably have to be turned off part of the year, since cooling them during the summer would not be part of the plan). Using climate data, the team outlined regions where the climate seemed amenable, and also incorporated the cost of electricity for running the servers and the potential upgrades in network infrastructure required for linking them to the cloud. Check out their table showing estimated cost savings here.

At the end of their analysis, they conclude that within certain constraints, both homeowners and cloud-computing companies could save money with this approach.

Not So Fast:

The very first problem that comes to mind is, of course, security. Sure, you can, as the paper suggests, make sure everything that runs through those servers is encrypted and take other precautions against meddling hosts. But there's a dissertation's worth of security research to be done on this question, and moreover, the actual risks, whatever they may be, won't matter when your customer hears that his data might be routed through some suburban basement. It sounds risky, and making it acceptable to cloud-computing consumers would be a deal breaker.

Furthermore, as the authors point out, electricity is 10-50% more expensive in residential areas than in business districts in the US. And if companies don't want to give homeowners free network upgrades, bandwidth becomes a serious issue too, as the servers could slow a home network to a crawl. These problems, along with the need to shut the servers down when the weather gets warm, severely compromise the usefulness of data furnaces to companies, since the kind and amount of computation they'd be able to handle would be fairly restricted.

Despite all this, the authors assert that having these servers situated in neighborhoods, campuses, or other centers of consumer usage means that customers will have faster access to information, a major benefit from companies' perspectives. But there's a catch-22 here. Because of the security-bandwidth-electricity trifecta, the servers would only manage low-priority computations. Those computations don't need to be done close to consumers---in fact, they're often cited as the kind of computations you can send to server farms in distant deserts.

Our Take:

Hooking these two needs together is a good idea. But putting servers in private homes could be a fraught experiment, and the researchers acknowledge as much.

It makes much more sense to try this out in places that are already equipped for information security---locked server rooms, and so on---and are themselves dealing with a surfeit of server heat.

University campuses and large office buildings, thus, are the natural choice for such a pilot project. Here's hoping someone will give it a try.

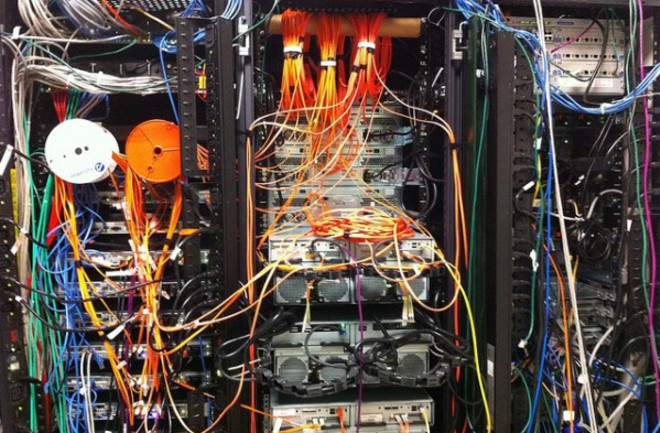

Image credit: hisperati / flickr