Jay W. Sharp

The prospector – a composite of many from across the eastern half of the United States – had heard the stories from the gold fields of California early in that year of 1849. Young men, with little future in impoverished rural communities and fields in the East and the Old South, spoke of little else. They said that miners had already dug several million dollars worth of gold out of California’s hills and mountains (at a time when a dollar had 25 times the value of today’s dollar). Why, a preacher himself had said that one party had found more than 76 thousand dollars worth of gold in less than two months. One man, he had said, had found more than five thousand dollars worth in two months. A 14-year-old boy had found more than three thousand dollars worth in only 54 days. A woman – a mere woman – had found two thousand dollars worth in six weeks. Surely any man willing to work hard could get rich. That’s what everybody said.

Leaving Home

The prospector, like his contemporaries, felt himself drawn to the gold fields of California like a leaf sucked into a whirlpool in a swirling stream. He saw visions of gold materializing out of stone and soil. He dared think about a real bank account, some land, a few cattle, a rock house and maybe even store-bought clothes and some new boots. It was by leaving right away that he could reach California by summer. He could work hard for a few months and with any luck at all, he would find gold and he would return home with some real money in his pocket.

The prospector thought about all of this as he approached the infamous Horsehead Crossing on western Texas’ Pecos River and the eastern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. He had elected to travel with a caravan out of San Antonio and take the Desert Trail to California—the route across West Texas, southern New Mexico, southern Arizona and southern California to San Diego. From there, he would turn north toward that town they called San Francisco. He would buy whatever he might need there for his mining venture and then go straightaway to the gold fields.

Our prospectors had come from Alabama by way of San Antonio, where he had lived with his wife and three children for two years in a single room in her parents’ small house with walls of coarse lumber and a roof of rough-hewn wooden shingles. Twenty four years old and illiterate, he had been able to find only occasional work as a wagon freighter, farm hand and cow puncher, making two, maybe three dollars a day when he could get a job. He owned two horses, a mule, an aging saddle, a wooden-handled Bowie knife, a flintlock musket and a .44 caliber Colt Model 1848 Percussion Revolver and holster—all recently inherited from his father. He especially treasured the revolver, which, hanging at his hip, gave him a sense of masculinity and security.

Somehow, he and his wife had managed to save $85, which they had cached in a small worn cotton cloth sack secreted in the drawer of a small table in their room. He had taken $50 when he left, surely enough to meet his needs until he got to the gold fields. He had left his wife with $35, surely enough to meet her needs until he returned; that woman knew how to handle money. He took with him one horse, his saddle, his mule, his weapons, ammunition, two blankets, two flannel shirts, a pair of heavy pants, a pair of heavy boots, an overcoat, matches, a coffee pot, a frying pan, a canteen, a water bucket, coffee, bacon, rice, beans, dried peaches and pipe tobacco. He would buy a pick, a long-handled shovel and a gold pan – the tools of the miner’s trade – when he got to San Francisco.

He promised his wife that he would return by the next summer, believing that would give him more than enough time to find gold in a place like California. He would come back with some real money in his pocket. They would buy 160 acres of San Antonio River bottomland. They would build their very own rock house. They might even send their children to school to learn to read and to write. They might have a little something they could share with their church. He remembered looking back to wave goodbye that morning he had left, his tearful but grimly determined wife with their bewildered children clasped around her long skirt and apron, her father with a look of yearning and maybe even envy in his eyes, her mother with a resigned and knowing expression on her face. He knew they would all pray for him.

By the time, in that mid-spring of 1849, when he and his caravan had reached Horsehead Crossing on the Pecos River and its murky and mineral-laden water, our prospector saw that grass for his horse and mule had begun to grow thin. He learned that the distances between springs and streams had become long and tortuous. He found that the heat of the looming desert already lay heavily on his shoulders during the day but that a biting chill penetrated the folds of his two blankets during the night.

He had heard that many prospectors had taken passenger ships to California. People said that you could take a sailing vessel clear around South America then sail northward up the Pacific coast to California. That could take six or eight months. Or you could sail across the Gulf of Mexico to the east coast of Panama, cross the disease-ridden and insect-infested isthmus by wagon or horse, and then sail in another ship up the coast to California. That could take even longer because you might have to wait for months to get passage north from the west coast of Panama. He had heard, too, that you would find the ships outrageously expensive, grossly overcrowded, wretchedly equipped, obscenely filthy, poorly supplied and disease ridden—hell under sails. Our prospector knew that he had made the right decision, taking an overland trail, but by the time he reached the Pecos, he could see that he faced a hard journey across the Southwest desert to California.

Across the Desert

From the Pecos, our prospector and his caravan would follow ruts carved by wagon wheels across desert basins and mountain passes, a trail that led them through western Texas to the Rio Grande, up the river to El Paso and on up to Las Cruces and Mesilla, across New Mexico and Arizona to Tucson, down the Gila River to the Colorado River juncture, across southern California into San Diego, and, finally, northward up the coastline to San Francisco.

From the Pecos to the Colorado River, he and his caravan traveled with the constant fear of the Indians, especially the Mescalero and Chiricahua Apaches, who hovered near them like avenging spirits. As summer came on, he felt the increasingly oppressive heat of the desert. He thrilled to the crackling thunderstorms that swept with awesome violence and beauty across the mountaintops. He watched his horse and mule grow lean, their ribs protruding, because of the relentless hardship, hunger and thirst. Every morning, it seemed, he had to draw his saddle cinch tighter and tighter before he could mount his horse. Like prospectors on the other trails west to California, he saw the desiccated carcasses of livestock abandoned by earlier caravans. He saw death awaiting spent draft animals and livestock left behind by his own caravan. He saw cast-iron stoves, wooden barrels, leather trunks, tools and even an anvil that had been discarded along the trail by travelers trying to ease the burdens on their mules and oxen. He saw cholera take the lives of good men. He saw an accidental gunshot wound take the life of another man, who had come from an Eastern city and knew little of firearms. Our prospector himself suffered from the flu and from diarrhea. Still, he pushed doggedly on, remembering his wife with their children clasped about her. He had promised to return by next summer, with some real money in his pocket. They would buy land, build a house, educate their children.

California and Gold

When our prospector arrived in San Francisco, having now departed from his caravan, he had $23. His mule had gone lame back up the trail, probably from bone bruises in the hooves, so he had had to buy a burro to haul his gear. He had to pay $2 for a long-handled shovel, $1.50 for a pick, and a $1 for a gold pan—the cheapest he could buy. Take it or leave it, the merchants had told him, we’ve got a thousand more who’ll pay it. He bought new supplies, and with a rising tide of other prospectors, he turned east for the gold mining region in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

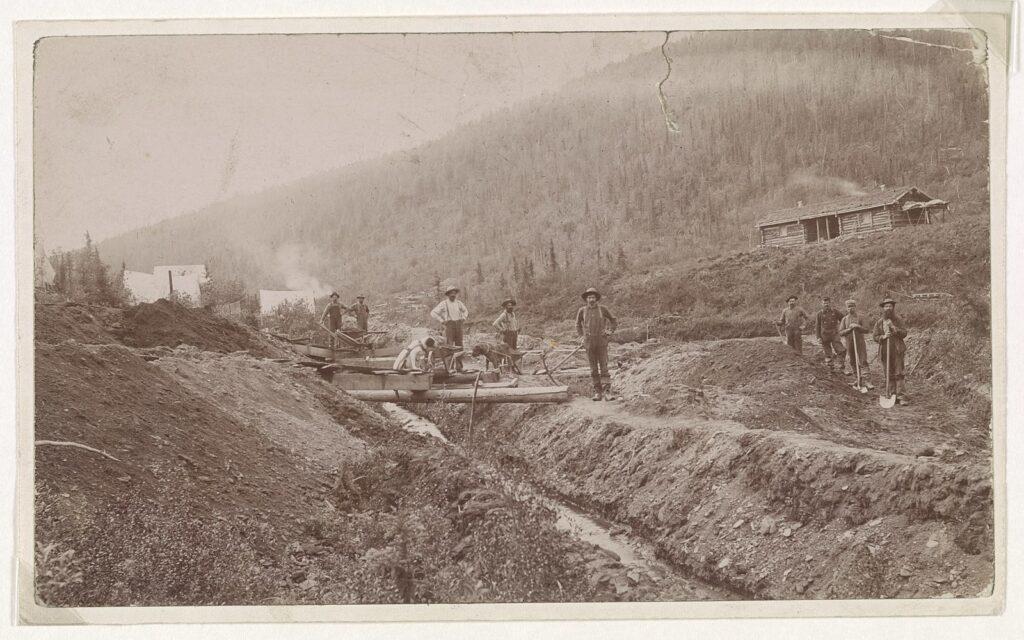

When he arrived, in the early fall of 1849, he found, to his astonishment and despair, that thousands had beaten him to the gold fields. Looking for a place where he could put his own shovel and pick to work, he wandered through the mining camps, which had been thrown up along the banks of streams and washes issuing from the mountain flanks. In a typical camp, “The hill sides were thickly strewn with canvass tents and bush arbors,” according to Colonel Richard B. Mason, California’s interim military governor (quoted by T. H. Watkins in Gold and Silver in the West), “a store was erected, and several boarding shanties in operation.”

Often, hundreds of men lined a promising stream, digging and panning for gold. Within months, they had recovered virtually all the gold from the gravels and sand that lay near the surface. They then attacked exposed bedrock, hoping to find flakes and maybe even nuggets trapped in the stony matrix. One miner, quoted by Watkins, said, “My diggings were about eighteen inches of bedrock. I managed to crevice and dig out about a dozen pans full per day from which about an ounce [worth $16] was daily realized. Out of this it required about $10 per day to supply my food, which was usually beef or pickled pork, hard bread, and coffee.” Another miner quoted by Watkins said, “…it was downright hard labor, and a man to make anything must work harder than any day laborer in the States.”

Finally, with fall closing in and his money nearly gone, our prospector stumbled into a mining camp that had just begun to sprout on the banks of a small and remote stream that held out the promise of a new “strike.” His spirits rising, he let himself think for a moment about his wife, their children, new land, a rock house, school. He put up a small tent that he had bought earlier for $1.50 from a prospector who was giving up and heading home. With hard searching, our prospector discovered, at the foot of an outcrop of quartz near a stand of pinyon pines, a shallow eddy with a sand and gravel deposit – a “placer” – in the edge of the stream. He had learned what to look for from the veteran miners.

His hands trembling, he waded into cold clear water of the eddy. He dug out a shovelful of gravel and sand, water streaming from the blade, and he emptied it into his gold pan. He squatted at the stream’s edge. He examined and discarded the stream pebbles in his pan. He filled the pan with water. He swirled the cloudy mix, washing loose sand and silt over the lip of the pan. At last, he discharged everything but the residue, a small handful of mud. He fanned it across the pan’s bottom, which measured about 10 inches in diameter. Nothing. He repeated the sequence. Again, nothing. He repeated it again. Still nothing. He repeated it still again. This time, in the dark smear in the bottom of his pan, he saw it: a yellow speck, not much larger than a flake of dandruff. It twinkled merrily in a ray of sunlight. He tried to not let himself get too excited – it might not be worth much – but he knew that he had found gold.

Early the following morning, he rushed into the mining camp. He filed his claim, which encompassed both the quartz outcrop and the placer, with a local merchant who also served as the district recorder. In preparing the claim, the recorder wrote down our prospector’s name, the site location and the date on a piece of paper. Our prospector, unable to write, prevailed on the recorder, as a favor, to prepare a notice, signifying exclusive legal right to the claim. He hurried back to his site to post the notice, which seemed to ratify the promises he had made to his wife.

The Hard Work of Mining a Claim

He fell to work at once, shoveling the placer gravel and sand into his gold pan, picking the occasional gold flecks and, rarely, a small nugget from the residue, stashing them in a small leather pouch. Within days, other prospectors appeared both upstream and downstream, filing their own claims, recalling their own dreams and promises. With the approaching winter – when rains and even traces of snow might fall, daytime temperatures would cool and nighttime temperatures could turn freezing – our prospector took time to build a small lean-to cabin with boards he had scavenged from the mining camp. Otherwise, he mined his claim compulsively, from first light to twilight, with a sense that fortune might lie at his fingertips. He worked perhaps 40 or 50 pans full of the placer material on an average day.

At nights, he sometimes visited with fellow miners, who gathered around campfires or in the larger cabins. They smoked their pipes, played cards, drank a little whiskey. They talked about big strikes that prospectors had found in neighboring foothills. They talked about their day’s finds, which seldom seemed to be worth the effort they had spent; new arrivals, who had come too late to find decent claims; a new saloon, which had good but expensive whiskey; the new girls, some of them known to veteran miners from previous camps; a new gambler, who, some said, cheated at the gaming tables; a thief, who got caught, tried and hung in a nearby camp; and the mercantile store, where the owner charged extravagant prices. Sometimes, they remembered home – their wives, their children, their dreams – and how they hoped that they could go back, buy land, build a house and educate their children. Sometimes, too, they spoke of prospects in other lands, for instance, the Rocky Mountains, which surely must hold fortunes in gold. They even talked about mining desert arroyos, where gold-bearing placers must have been deposited by streams that dried up many years ago. “All you’ve got to do is find it,” they said. Maybe the Rockies or the desert might hold the most promise for the future. Prospectors had already overrun the California mining region.

As winter gave way to spring and summer came – the season when our prospector had hoped to return home with some real money in his pocket – he had made barely enough to feed himself and his horse and burro. He had neared the bottom of his placer, however, and they said it is at the bottom where you usually find the most gold because its density caused it to filter down through the sand and gravel to the rock floor. A prospector working near the bottom of a placer just downstream had found a nugget as big as a kernel of corn in his pan. Another, just upstream, found a sliver of gold in the bedrock in his claim. They said a man from a big mining company had come around asking about buying some claims. They said claim jumpers now hung around, looking for unguarded or neglected sites like vultures searching for carcasses. Our prospector made sure to wear his .44 Colt Percussion Revolver, his cherished hold on security, on a regular basis. With hopes rising, he intended to protect his claim fully. As the days wore on and he stripped the bottom of his placer, he began to find slightly more gold flecks and nuggets in his pan, just like other prospectors had said. He cached it in his leather pouch, always attached to a rawhide thong that he hung around his neck, inside his shirt.

As a second winter passed, a second spring, and a second summer, he knew that his wife, back in San Antonio with the children and her parents, worried and fretted about him. He knew that she would have told their friends that when he returned home, with some real money in his pocket, they would buy some land, build a house, educate their children.

Having exhausted his placer, he turned now to the quartz outcrop, driving his pick, day after day, into the rock surface. He hammered the stone fragments into rubble, which he panned just as he did the placer gravel and sand. He teased out more flecks and small nuggets of gold, stashing them in his leather pouch.

By the beginning of fall, a full year after he had filed for his claim and more than a year after he expected to be home, he had accumulated about eight or ten ounces of gold. He had grown weary from the brutal and relentless work. He yearned for his family and home. He knew that he could not take time to go back for a visit because he might forfeit his claim if he left it unworked for more than 10 consecutive days. Then, one day, a man who represented a big mining company came around buying claims. The company had the capital and machinery to undertake big-scale operations. The man offered our prospector $2500 – more money than he’d ever seen in his life – for the rights to his site.

Moving On

A few nights later, our prospector went over to the saloon, with some real money in his pocket, to have a little whiskey just to celebrate. Early the next morning, he planned to start for home and his family and his dreams. He wondered whether his wife and children would recognize him with a full black beard—the trademark of the prospector. He talked to other miners who had sold their claims to the man from the mining company, drinking a little whiskey just to celebrate. He knew that a brotherhood born of shared hardships and dreams was fading from his life. He realized that he would miss campfires and cards and yarns and local gossip. When he left the saloon, he could feel the earth swaying beneath his feet.

Our prospector woke up the next morning, lying in the dirt at the door of his lean-to cabin. He felt a pounding ache in the back of his head, as if he had been kicked by a mule. He could feel the blood crusted in his hair, his beard and his shirt collar. He felt for the money he had had in his pocket. Gone. He reached for his treasured .44 Colt Percussion Revolver. Gone. He felt for the few ounces of gold in the leather pouch at his neck. Still there. Thank God.

Through the fog of the pain and a numbing hangover, he looked mournfully at the quartz outcrop and the stream eddy that had been his claim. Remembering his promises, he knew that he couldn’t go home to his wife and children without some real money in his pocket. He wondered idly if she still prayed for him.

He took stock. He had some gold he could sell for a little money. He still had his horse and saddle and his burro. He still had his camp gear, his musket, his Bowie knife and a few clothes. He still had his shovel and pick and gold pan. Maybe he would try the Rocky Mountains next. Maybe the desert placers. He knew that any man willing to work hard could get rich. That’s what everybody said, and he still had his dreams.

In preparing this composite sketch of a prospector, I have drawn most heavily from The Miners (from the Time-Life series on the Old West) by Robert Wallace, Gold and Silver in the West by T. H. Watkins and Gold Rushes and Mining Camps of the Early American West by Vardis Fisher and Opal Laurel Holmes. Those three books paint a rich story of the prospectors and miners of the Old West.

SOME OLD MINING TOWNS

Calico Ghost Town, Ca

Randsburg, Ca

Trona, Ca

Oatman, Arizona

Jerome, Arizona