Last year’s hurricane season devastated parts of Louisiana with no reprieve.

In August 2020, Hurricane Laura made landfall in Louisiana as a category 4, triggering a “catastrophic” storm surge of up to 18 feet above ground level. The storm killed dozens of people in the state and inflicted $17.5 billion in damage. Two months later, Hurricane Zeta, a Category 3, left half a million people without power and caused $1.25 billion in damage.

In total, five named storms struck Louisiana in 2020. As the state still reels from the destruction, another significant hurricane is now barreling toward the coast.

Ida is rapidly intensifying over the Gulf of Mexico, and is expected to make landfall in Louisiana as a major hurricane — category 3 or stronger — on Sunday, the same date Hurricane Katrina made landfall 16 years ago.

Hurricanes are common in the Gulf Coast, but the damage expected from Ida may throw Louisiana’s already ravaged infrastructure into stark relief.

Sabarethinam Kameshwar, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Louisiana State University, said the repeat nature of hurricanes in the Gulf has taken a significant toll on people’s lives. Many Lake Charles residents whose homes were flattened by recent disasters have spent the last few months rebuilding and living in hotels or temporary shelters, he said. Some are still waiting for federal disaster aid to arrive.

“As these hurricanes happen back to back, there are multiple impacts for people whose houses got damaged during Laura,” Kameshwar told CNN. “A lot of those houses have still not been fixed yet, so for people who have already damaged houses, they might have further damages and [the hurricane] will make things worse for them.”

Roishetta Ozane, a 36-year-old mother of six, is one of those residents.

Ozane’s family has been living in trailers provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency since 2020’s back-to-back hurricanes — which were followed by a crippling winter storm and severe flooding. She formerly lived in subsidized housing that has yet to be rebuilt, and as a single mother she cannot afford an apartment big enough to fit a family of seven.

“We are on the one-year anniversary of Hurricane Laura, having to run from another storm,” Ozane told CNN. “People are very emotional already because one year later, we’re still seeing the area looking like it did when we returned last year after the evacuation was lifted.”

Louisiana residents are now bracing for Hurricane Ida. Emergency officials have urged residents to move out of the storm’s path, which is dotted with oil and gas facilities that could also pose environmental hazards if they are damaged.

On Thursday, Gov. John Bel Edwards declared a state of emergency, and noted the region is still reeling from the 2020 season.

“We’re not recovered. Not by a long shot,” Edwards said at a news conference. “We still have businesses boarded up from the last [hurricane]. Homes have not yet been repaired and reoccupied. Or if they are damaged to the point where they need to be demolished and removed, in many cases that hasn’t happened either.”

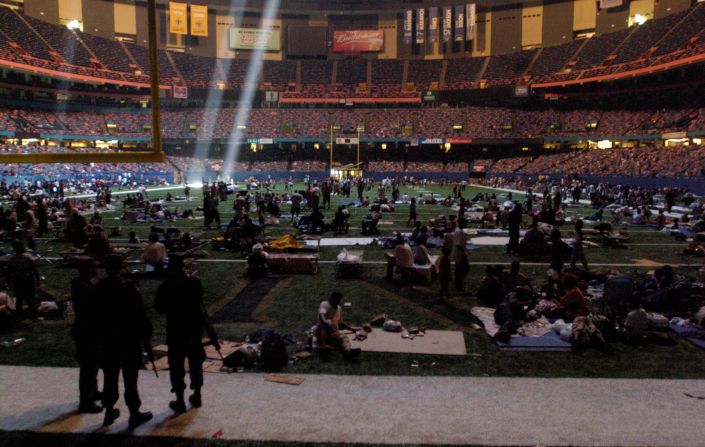

Retired Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, the widely praised former commander who led relief efforts in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, said evacuation efforts have proved even more challenging during the pandemic. Last year, Lake Charles residents were evacuated to New Orleans, but the spread of the coronavirus stopped emergency responders from using the usual large evacuation sites.

Due to the South’s low vaccinate rates, Honoré said the storm could exacerbate the pandemic, making emergency response more difficult.

“As they leave, wherever they leave, they can be taking more Covid with them whether they’re going to North Louisiana or a hotel in Tennessee,” he said. “It is providing a vessel for the virus to spread out of Louisiana, because people refuse to take the shots.”

Honoré said state and federal officials need to evacuate people living in mobile homes, like Ozane and her family, and those in low-lying parishes as soon as Saturday.

In pictures: Hurricane Katrina

Many Lake Charles residents, like Ozane, are still reeling from the destruction they faced during Laura and the extreme flooding event in May. Because of the cascading disasters she experienced in the last year, she intends to evacuate her family to Houston as soon as possible.

“It’s very scary,” she said. “It’s bringing up so many feelings that haven’t recovered yet, and we’ve already lost everything. We haven’t received any supplemental funding to help us get anywhere further than where we were last year.”

Scientists say the climate crisis is making tropical cyclones worse, as warmer ocean water and air temperatures provide the storms more fuel. A recent state-of-the-science report from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded the increase in tropical storm intensity the last 40 years can’t be explained by natural causes alone — and that humans are a contributing factor through global warming.

“We have good confidence that greenhouse warming increases the maximum wind intensity that tropical cyclones can achieve,” Jim Kossin, senior scientist with the Climate Service, an organization that provides climate risk modeling and analytics to governments and businesses, previously told CNN. “This, in turn, allows for the strongest hurricanes — which are the ones that create the most risk by far — to become even stronger.”

Allison Wing, an assistant professor of atmospheric science at Florida State University, said scientists are finding the rainfall in hurricanes is getting more intense, which will lead to more flooding. She also noted that “compound events” — when several disasters strike in succession — have an increasingly significant impact.

“In addition to just having one hurricane after another, you could have a hurricane and then have an extreme flooding event,” Wing told CNN. “And then you also have to worry about these things occurring not just in the same place at the same time, but also within the same region or country.”

After the Gulf was pummeled by back-to-back hurricanes and wildfires were raging across the West Coast, a historic winter storm devastated Texas and parts of Louisiana. Wing said compound events, whether it’s the same region or country, stretch emergency resources thin.

“That’s something that national organizations like FEMA have to manage, how to deploy their resources across multiple threats in multiple areas,” she said. “And so this issue of compound events of all types of extremes is only going to become a bigger problem going forward.”

Hurricanes are fueled by warm ocean water. As the planet warms, hurricanes may become more frequent, as well as more intense. Wing said that it’s still scientifically uncertain how the number of hurricanes will evolve over time, but it’s important to prepare for the multiple hazards to come as the climate crisis amplifies extreme weather.

Ozane, who now runs a disaster response group called The Vessel Project based in Lake Charles, said emergency management systems and disaster policies also need to be reworked, because the people who need the most assistance typically do not receive them due to barriers and social inequities.

“Southwest Louisiana will not be a climate sacrifice,” she said. “We need to make sure that the federal government and everybody else have not forgotten about us.”