They call Ross Peeples "The Mayor" in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The nickname is weighty but apt for the second-year manager of the Barnstormers, the local Atlantic League team. His job requires of him a political ethos: To win, people must know you and you must know people.

There are no passels of scouts and analysts informing player acquisitions in the Atlantic League. Roster additions tend to result from networking and back channels -- primitive methods that, when united with baseball's always-slick morals, can lead down regrettable paths (the Barnstormers have erred by recently employing abuser Danry Vasquez and Steve Clevenger, whose insensitive Twitter remarks cost him an MLB career). The more people you know, the more players you'll hear about, the better your odds of success.

There was nothing unusual then about Peeples, who pitched for the Barnstormers from 2005-14, receiving a tip from an associate the way he did earlier this season. The informant was Logan Schafer, a veteran of six big-league seasons who'd spent a fortnight in Lancaster in 2016 before signing with the Minnesota Twins. Schafer was advocating for a buddy he'd played and roomed with at California Polytechnic State University.

"I just said, 'Hey Ross, this is a guy who, if he has half of what he had seven years ago, he'll be the best player on your team,'" Schafer told CBS Sports.

Such qualifiers are common in the Atlantic League, where rosters are stocked with players past their salad days. So far in 2018, Lancaster has employed eight former big-leaguers.

Schafer assured Peeples the player he had in mind, an outfielder, was his kind of guy -- one possessing a strong character and a good work ethic who would fit in well. The dude just wanted a chance to play baseball. There was, however, a catch.

"He said, 'It could be a good story once it's all said and done,'" Peeples said. "'Thing is, he hasn't played in eight or nine years.'"

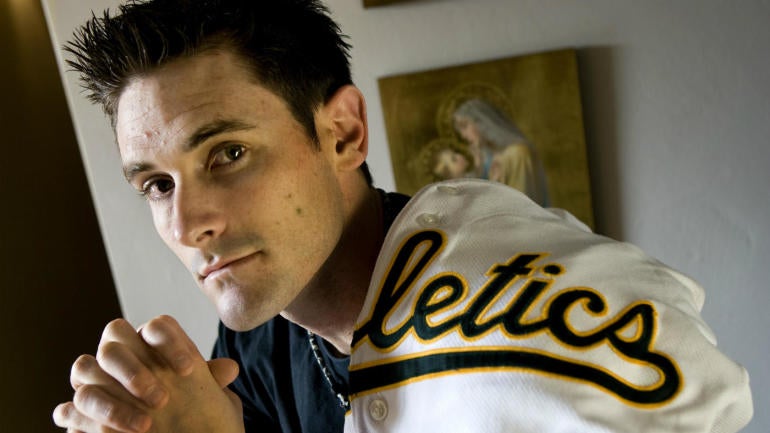

Such is how Grant Desme found himself in professional baseball again, more than eight years after leaving at the height of his powers to pursue a lifetime in the priesthood.

No. No is the answer to the question everyone asks Desme.

Forty-three percent of the players drafted in the second round of the 2007 MLB Draft have reached the majors, per Baseball-Reference. Had Desme stayed in the game, that percentage would almost certainly be a touch higher.

The question that everyone asks Desme goes something like this: If you could do it all over again and pick baseball, would you?

"I get asked that quite a bit, and sure it would have been nice to see where my career had gone if I didn't enter the monastery," he said, "but the amount of gifts and formation I received the seven years living at St. Michael's are priceless -- and those are things that are going to be with me for my entire life."

Desme speaks in a calm, confident tone. He's thoughtful, not diffident. There's no reason to doubt him when he says he's grateful for the experiences he had at St. Michael's Abbey, located in Silverado, California.

Still, inquiring minds must know: What drove Desme to leave the abbey last August, more than seven years after he walked away from a career that could have delivered fame and fortune?

To understand Desme's acts, one must understand his past. When he joined the abbey, he said the toughest dreams to leave behind were not baseball-related. Winning a World Series, becoming a multimillionaire before he turned 30, having random people tweet mechanical advice at him -- those aspirations were never that important. What was important to Desme, and what he found hardest to detach from, was the craving to get married and have children. Embracing monastic life meant ending a relationship he thought had marriage potential.

Desme subdued thoughts of his alternate reality for a time, but they eventually overpowered him, validating existential philosopher Søren Kierkegaard's claim that "the most painful state of being is remembering the future, particularly the one you'll never have." Desme may or may not know the quote, but he understands the sentiment.

"The whole time really I was wrestling with what way I was being called to give myself to Christ," he said, explaining how he felt God had been calling him to service. "The desire to get married increased more and more the longer I was at the monastery, while that didn't necessarily happen with the desire to become a priest. I came to the conclusion that God was calling me to married life."

If Desme has regrets, they aren't evident in how he talks about life at the abbey. He cherished being nurtured intellectually and spiritually, with extensive study appealing to his attentive nature (Schafer described him as "the kind of guy who understands things"). Meanwhile, the close-knit community allowed him to forge meaningful relationships with his fellow brothers,whom he labels his best friends. Those at the abbey, including his spiritual director Father Ambrose Criste, have stayed in touch and assisted Desme since he departed.

Father Criste and the rest of the Abbey's leadership are accustomed to this outcome, anyway. As Desme puts it, "People come, stay for various amount of times and leave -- or they stay forever." Few stay forever. Jeff Passan, who wrote the definitive article about Desme's retirement, noted about 30 percent of seminarians at St. Michael's Abbey are ordained as priests.

To understand Desme's acts, one must understand his past. How he considered the priesthood after injuries limited him to 14 games in 2007-08. How he stayed healthy in 2009 and hit .288/.365/.588 across two levels while becoming the minors' only 30-30 player (he homered 31 times and stole 40 bases on 45 tries). How he provided an encore performance in the Arizona Fall League by hitting .315/.413/.667 with 11 homers in 27 games. How he entered the next spring ranked as one of the A's best prospects, with scouting reports pegging him as "an everyday corner outfielder with 30 home runs a year." How he would've began the ensuing season at Double-A, and possibly finished it in the majors. How, even if he took longer to reach the Show, he would've likely amassed enough service time to become a free agent last winter.

Perhaps Desme would have injured himself time and again, his body proving unable to meet the demands of a 162-game season each year. Maybe his strikeout tendencies would have left him exposed against advanced pitching. He could have reached the majors, then slipped into the inescapable quad-A purgatory the way those have whose names surrounded his on those old prospect lists: Chris Carter, Michael Taylor, Michael Ynoa, Grant Green.

None have played in the majors this season. Taylor hasn't played in the majors since 2013 -- would that have been Desme's fate? See? See how the most painful state of being is contemplating an unlived future? Satisfaction will never sprout at the crossroads linking conjecture and ego.

Desme does not sound like someone wondering about what could have been. He sounds like someone secure in what he is, secure in what he wants, secure in what will make him whole and bring him closer to what he believes to be his purpose.

"I think the one thing I left the monastery with that I really learned, that is very close to my heart, is just the value of good fatherhood. The power of that," he said. "It was put on my heart to be a great father."

Truthfully, Desme's return to baseball dates back nearly a year. When he left the abbey last August, he sent out a horde of emails hoping for a job lead. One surfaced in the inbox of retired all-star slugger Mike Sweeney, who is involved with Catholic athletes.

"He had received an email from Ave Maria University asking him if he knew anyone who could be their head baseball coach," Desme said. "Once I saw that email I was like, 'Oh man, this is pretty clearly what I'm supposed to do.'"

Whether an act of providence or good timing, Desme landed the job. Ave Maria University is a small, private Catholic school located in Florida, about three hours south of Tropicana Field. An estimate from 2015-16 had enrollment around 1,000 undergraduates -- hardly the makings of an athletic powerhouse.

Desme embraced the potential at Ave Maria to meld his faith with baseball. Even now, as he plays for the Lancaster Barnstormers, he remains the Gyrenes' head coach. The university is supporting his comeback attempt, permitting him to work remotely over the summer. He's still recruiting, organizing practices and fall ball, and dealing with other administrative issues -- he just isn't there in the flesh.

Desme wanted to play again after he left the abbey, but the circumstances didn't work out. He found himself egged on by friends this spring, so he began taking batting practice. The AMU players caught on to what was going on.

"It was under wraps for a couple of weeks," said Brett Rosin, AMU's pitching coach and Desme's successor if he lands a professional contract. "Once he started to work, guys started to get a little suspicious and they started to ask each other a couple questions. Once that got wind to us, he called a team meeting and he let them know he was going to play again."

In 11 games since joining the Barnstormers, Desme has played both outfield corners and has hit .308/.349/.462 with a home run and two steals. He took off the weekend after he spoke to CBS Sports to attend his sister's wedding. Otherwise, all systems are go.

There are other promising signs beyond the stat line, too. Peeples has been impressed by Desme's batting eye, particularly after such a long layoff in between seeing professional pitching. Schafer, who checks in often, believes Desme is rediscovering his old swing, suggesting more barreled balls lay ahead.

While it's unclear if and how many big-league teams are interested in adding Desme to their organization, there is sufficient reason to believe scouts are watching and filing reports. Since the season began in late April, the Atlantic League has lost nearly 20 players to the minors. The Seattle Mariners and New York Mets have been among the most aggressive in foraging the league. Were the Mets to sign Desme, the comparisons to Tim Tebow would run rampant. But for as lazy as the comparison feels -- both are industrious, pious outfielders with raw pop who took extended sabbaticals from baseball -- there is something to it.

Desme, like Tebow, will have to overcome years of missed development to work his way up the ladder. Depending on what the scouts see, a recommended initial assignment could have him playing at levels where the average player is a decade younger. Tebow, who turns 31 in August, is the oldest qualifying position player at the Double-A level. There are only two other qualifying hitters older than 28: 30-year-old Jerry Sands and 29-year-old Corban Joseph. Consider also that Tebow, who is more than a year and a half younger than Desme, has already accumulated more minor-league appearances. Desme trails even when his games in the AFL and Atlantic League are added in.

Signing Desme is betting on his character and his unteachable athletic gifts transcending his lack of experience. Those closest to the situation believe a team will take the plunge before the season ends, likely when he shakes off the rust. "It's just going to take time for him to get everything down, everything back," Peeples said. "You go by the tools, you see where has average-to-plus speed, average-to-plus arm, average-to-plus power, average-to-plus hit-for-average. You can definitely see the traits."

Instincts are another point in Desme's favor. He was considered a heady player the first time around, and his feel for the game has been amplified by his time spent in the dugout. Peeples said Desme is in every game mentally, observing the pitcher and asking tactical questions about defensive positioning and the like.

From a certain perspective, signing Desme might represent a gamble for a different outcome: That he hangs up his spikes in a year and embraces a coaching or development role. Those who have worked alongside him believe he has the temperament and emotional intelligence to thrive in the role.

"It's a very patient mind set that he has," Rosin said, crediting Desme for helping him maintain perspective. "His calm demeanor usually brings calm around some of the pressure-filled situations that the game and even the job bring about." Schafer added: "He understands commitment. He understands hard work. He's an easy guy to listen to."

For someone as drawn to the idea of fatherhood as Desme, it makes sense that he excels as a coach -- a mentor role that, in a sense, allows him to serve as a proxy dad to his team. The younger Rosin repeatedly expressed his admiration for Desme and his ability to form bonds with AMU's players, some of whom were in elementary school the last time he played in the minors.

Desme's commitment to detail shines through in other ways. AMU isn't a large program, but they're pursuing technology embraced by the power conferences. Then there are the goals he hopes to achieve as a coach.

"Being there for my guys, to help them, to direct them in life, not just on the field but in the classroom and the decisions they make in their daily lives," he continues, "to help them to become better men than the men they were when they showed up at the university, so when they leave they're better prepared to be in the workforce, to have a family, to be a good husband, a good father."

A good father. It had to end there, right?

To understand Desme's acts, one must understand his past. He knows nothing is guaranteed, in baseball or otherwise. He would love to play on, but will be happy to return to Ave Maria this fall if that's how things break. He isn't prone to housing regrets. He isn't one to second-guess his decisions. He follows the path he believes has been laid out for him by his maker.

"I'm grateful that I did it and the adventure just continues," he said. "We'll see what God has in store for me."

To understand Grant Desme, one must understand that he will go where he feels called.