The Dinner Party: A Table for the World’s Most Influential Women

In what is known as the most important feminist exhibition of the century, Judy Chicago’s installation ‘The Dinner Party’ has attracted 15 million visitors. Discover more about the work that made the artist a pioneer of feminist art.

After years of hard work, it was finally time: in the spring of 1979, American artist and author Judy Chicago (b. 1939) was able to show the installation The Dinner Party, the large-scale artwork that came to characterize the ‘70s art scene, to the public. Thirty nine influential women who influenced and contributed to society were invited to the world's most important dinner party, including Pharaoh Hatshepsut, Abbess Hildegard of Bingen, and American artist Georgia O'Keeffe.

The start of the second wave of feminism took place in the late 1960s and continued until the late ‘70s. The concept was coined in 1968 with the aim of separating it from the first wave of feminism, where the focus was on legal rights and the right to vote. During the second wave, the focus was on legal reforms that applied to women: free abortion, access to contraception and recognition of marital rape. Society began to question the prevailing gender roles and women's right to their bodies.

A few years after the second wave of feminism had begun, Judy Chicago went to a dinner party. The year was 1974, the same year that The Dinner Party began. During dinner, “The men at the table were all professors,” Chicago recalled, “and the women all had doctorates but weren’t professors. The women had all the talent, and they sat there silent while the men held forth. I started thinking that women have never had a Last Supper, but they have had dinner parties.”

Related: Marina Abramović: Not Just Any Body

She started her work that year and with the help of 400 volunteers, The Dinner Party was ready in March 1979. The installation is today considered the first large-scale feminist work of art and serves as a symbol of women's history in society. The work became not only an important symbol of the feminist art of the ‘70s, but also a milestone in 20th-century art.

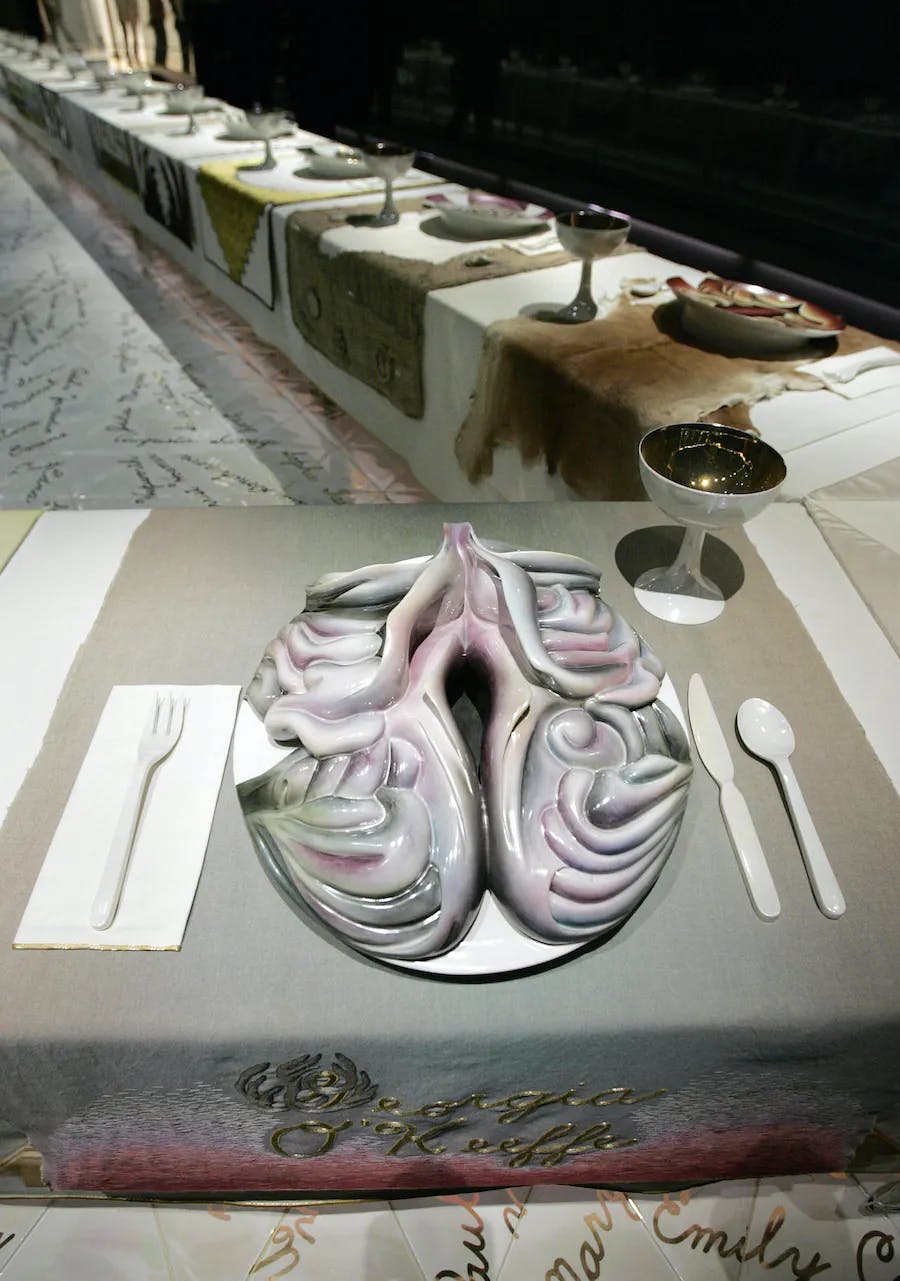

The Dinner Party comprises a triangle in which each table is 48 feet long. Each table has 13 nameplates, making a total of 39 place settings. The tables symbolize three different periods in history and represent the women who shaped those periods. In chronological order there are women such as Hatshepsut, Hildegard of Bingen, Artemisia Gentileschi, Georgia O'Keeffe, Mary Wollstonecraft and Virginia Woolf. The first table pays tribute to prehistoric women from the Roman Empire, the second pays tribute to women from the beginning of Christianity to the Reformation, and the third pays tribute to women from the American Revolution to the feminist revolution.

Related: Artemisia Gentileschi: 5 Extraordinary Facts

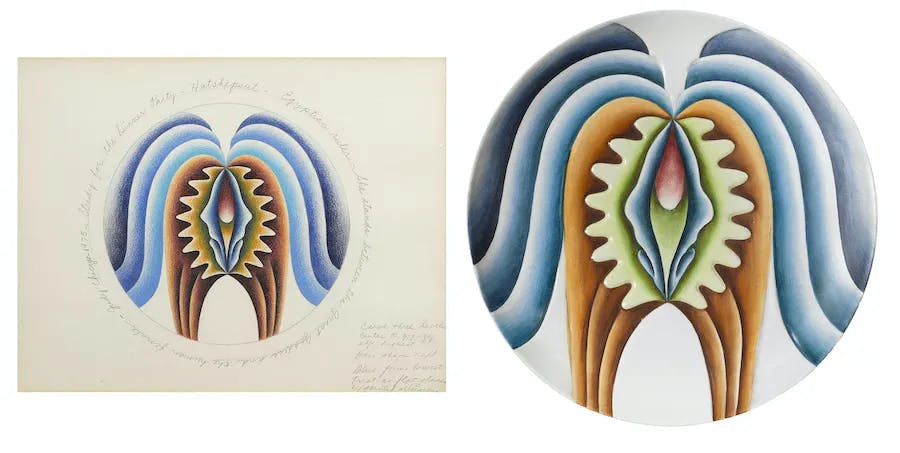

The tableware consists of embroidered runners with the woman's name, or a symbol that has a connection to what the woman accomplished, glass or goblet, porcelain cutlery, gold embroidered napkins and hand-painted Chinese plates. For the plates, Chicago based them on butterfly and flower motifs, which in turn created a motif reminiscent of the female genitalia, the vulva to be more precise. Each plate has its own motif and expression, based on each individual, except for the freedom and women's fighter Sojourner Truth and the suffragette Ethel Smyth.

In the chronological order, the appearance of the plates changes, not only by way of subject, but also the design. The closer we get to modern times, the more evolved they become. The idea is that the design should show how the independence and equality of the modern woman has grown over the years.

The triangular shape of the installation has a great significance as it has long been a symbol for the woman. The number 13 refers to the number of people attending the Last Supper, which is an important comparison for Chicago as the only people invited were men.

Related: Louise Bourgeois: Mother of Modernity

The Dinner Party stands on 2,300 white-glazed ceramic tiles, called The Heritage Floor. There are an additional 999 women represented here. Like the 39 women in The Dinner Party, these women are the ones who influenced the story. In actual fact, there are actually 998 women, as the Greek sculptor Kresilas was mistakenly thought to be a woman.

For the work, Chicago used crafts that were considered typically ‘female’, including embroidery and textile work. She wanted these artists' media to take their place in the finery of art and also for The Dinner Party to be considered ‘real’ art.

The installation has toured around the world and a total of 15 million people have seen the work. Since 2007, The Dinner Party has been at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

Related: The 9 Most Important Feminist Photographs

Reactions to The Dinner Party varied, many were captivated by the work while some criticized it. It was called kitschy, vulgar and exclusionary. However, art critic Roberta Smith pointed out, "Its historical and social significance is greater than its aesthetic value."

Hortense Spillers, an American literary critic and academic in Black feminism, criticized the installation for the lack of diversity. Of 39 women, only one black woman is represented – Sojourner Truth, whose plate is adorned with a motif depicting three faces, while the remaining women's plates, except for Ethel Smyth (with a piano), are decorated with various depictions of the female genitalia. The American author and feminist Alice Walker was also critical of the homogeneous representation and said, particularly of Chicago’s representation of Sojourner Truth: “It occurred to me that perhaps white women feminists, no less than white women generally, can not imagine Black women have vaginas. Or if they can, where imagination leads them is too far to go.”

Related: Cindy Sherman: An Overexposed Psyche

Chicago's response to the criticism was to point out that all of these women are included on the Heritage Floor and that focusing solely on who is at the table is "to over-simplify the art and ignore the criteria my studio team and I established and the limits we were working under."

The much-debated work is still a topic of discussion today, but despite its shortcomings, it is described by the Brooklyn Museum as an important and iconic work that has become a milestone, not only for the feminist art of the 1970s but also for the entire century.

Related: The 15 Most Expensive Female Artists

About 40 years later, Judy Chicago created a number of limited edition plates based on The Dinner Party. The plates produced were those of Elizabeth I, Amazon and Sapfo. Chicago’s so-called ‘test plates’ have achieved many thousands at auction, as have her previous works, including Fresno Fan ($50,000) and Yellow Series ($24,000)

Discover the latest news from the art world with Barnebys Magazine

This is an updated version of an article originally published on June 30, 2020.