Hieronymus Bosch.

Hieronymus Bosch.

Who was Hieronymus Bosch

Hieronymus Bosch, also known as Jheronimus van Aken, was a renowned Dutch painter from Brabant who lived from around 1450 to August 9, 1516. He was a prominent figure in the Early Netherlandish painting school and is well-known for his extraordinary depictions of religious themes and stories. Using oil on oak wood as his primary medium, Bosch created fantastical illustrations that often portrayed hell in a macabre and nightmarish manner.

Although not much is known about Bosch's personal life, there are some existing records. He spent the majority of his life in the town of 's-Hertogenbosch, where he was born in his grandfather's house. His ancestral roots can be traced back to Nijmegen and Aachen, which is evident in his surname "Van Aken." Bosch's unique and pessimistic artistic style had a profound influence on Northern European art during the 16th century, with Pieter Bruegel the Elder being his most well-known disciple. Today, Bosch is recognized as a highly individualistic painter who possessed a profound understanding of human desires and deepest fears.

Determining the authorship of Bosch's works has been challenging, and only about 25 paintings are confidently attributed to him, along with eight drawings. Approximately six more paintings are confidently associated with his workshop. Some of his most celebrated masterpieces include triptych altarpieces, notably "The Garden of Earthly Delights."

Key concepts

Bosch was a pioneering artist who introduced abstract ideas into his artwork, frequently using the narrative structure of the triptych. Experts and scholars have identified various contemporary themes in his storytelling, such as ecological, social, and political issues. However, his most renowned creations, particularly his magnificent masterpiece, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), are filled with religious symbolism and revolve around humanity's eternal moral conflict between recklessness and virtue.

Recognized by many as the "originator of demonic imagery" and a conveyer of visual absurdity and mockery, Bosch's artworks have posed significant challenges for critics and historians to decipher. His enigmatic paintings have earned him the nickname "El Bosco" in Spain, where he was highly esteemed even before the nineteenth-century revival of interest in his art. In fact, Bosch is often regarded as the "first Surrealist" and was acclaimed by the renowned psychoanalyst Carl Jung as the pioneering "explorer of the unconscious."

In contrast to Netherlandish painters like Jan van Eyck, whose style was characterized by smooth and precise brushwork, Bosch's artistic technique is dynamic and diverse. His vibrant brushstrokes exhibit a remarkable energy. Additionally, his exceptional attention to detail can be traced back to his early experience as a draughtsman, which distinguished him as one of the first Netherlandish artists to create drawings as independent artworks rather than solely preparatory sketches.

Certain historians have highlighted that the source of inspiration for the distinctively surreal and diabolical creatures that inhabit Bosch's artworks can be traced back to religious manuscripts dating from the late medieval period to the Renaissance. As early as 1605, the Spanish monk José de Sigüenza observed that Bosch's paintings were akin to "books of immense wisdom and artistic significance." He further noted that any perceived absurdities within the artworks were not the artist's, but rather reflections of humanity's own follies and delusions. Sigüenza regarded Bosch's paintings as painted satires, offering sharp critiques of human sins and irrational behavior.

Hieronymus Bosch, St. John the Baptist in Meditation, c.1489. Oil on panel, 48.5×40 cm. Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, St. John the Baptist in Meditation, c.1489. Oil on panel, 48.5×40 cm. Lázaro Galdiano Museum, Madrid.

Early life and training

Jheronimus Anthonissen van Aken was born approximately between 1450 and 1456 (the exact date of his birth remains uncertain but has been estimated based on a self-portrait from around 1508). He was the son of Antonius van Aken and Aleid van der Mynnem, and he was born into a prosperous household in his grandfather's residence in the affluent and culturally vibrant town of 's-Hertogenbosch, which was part of the Duchy of Brabant in the Netherlands. His grandfather, Johannes Thomaszoon van Aken, was a highly esteemed painter in early fifteenth-century 's-Hertogenbosch and established a remarkable artistic legacy, as four out of his five children, including Antonius, became painters as well.

Aside from these details, not much is known about Bosch's early years, except for the fact that in 1463, a catastrophic fire destroyed around 4,000 houses in 's-Hertogenbosch. It is believed that Bosch witnessed this devastating event, which likely had a profound impact on him. Art historian Claire Selvin suggests that this tragic incident may have influenced Bosch's later artworks, some of which depict raging fires in the background, reflecting the lasting impression of the destructive event on the artist.

As a young man, Jheronimus adopted the name Bosch as a tribute to his hometown, which was locally known as Den Bosch or "the forest." Unfortunately, very little is known about his training since he left no notebooks, letters, or other artifacts. However, town records from s-Hertogenbosch in 1475 indicate that Hieronymus was listed as a member of his father's workshop. It is reasonable to assume that his father, possibly aided by one of his uncles, taught him the art of painting. Despite this knowledge, the origins of Bosch's extraordinary imagination remain elusive.

Around 1480-81, Bosch married Aleid van der Mervenne, the daughter of a merchant. Aleid, who was older than Bosch, brought with her a substantial inheritance, including a family property in the nearby town of Oirschot, where they settled. It is believed that Bosch never ventured far from his immediate surroundings and did not travel extensively. According to Salvin, through Fischer, Bosch benefited from the financial resources, land, and social status that came with the marriage. Soon after their union, Bosch established his own workshop, marking a significant turning point in his career as an independent artist. This allowed him to form connections with influential patrons, including royalty.

In 1486, Bosch's name and profession were recorded in s-Hertogenbosch's town records, designating him as an Insignis Pictor or "Distinguished Painter." It can be speculated that because s-Hertogenbosch was under Roman Empire governance, Bosch was likely familiar with the art of the Renaissance, which had an impact on Flemish painters. At the age of around 40, in 1488, Bosch joined the Brotherhood of Our Lady, a highly conservative religious association consisting of around 40 influential citizens of 's-Hertogenbosch and 7,000 "outer members" scattered across Europe. The Brotherhood, to which Bosch's father had once served as an artistic advisor, was devoted to the Virgin and held great respect throughout Catholic Europe. It is believed that some of Bosch's earliest commissions for devotional artworks came through the Brotherhood, although it is uncertain if any of these works have survived to this day.

Regarding one of Bosch's early known works, the Crucifixion with Saints and Donor (c. 1485-90), Fischer suggests that, while its original display location is unknown, the painting served a typical purpose of ensuring salvation for the donor depicted kneeling at the base of the cross, similar to other devotional artworks of that period. This particular painting stands somewhat apart from the rest of Bosch's body of work, which often features eccentric, disorienting, and unsettling compositions. However, Bosch would later apply his distinctive style to various religious subjects.

However, art critic Tim Smith-Laing challenges the notion that Bosch was an outsider or unconventional in any way. While some speculative research in the 1940s attempted to associate him with a heretical sex cult called the Adamites, and there were suggestions in the 1960s that he may have experienced hallucinations from consuming ergot-contaminated wheat, mainstream academic opinion paints a much more conventional picture. There is no evidence to support these theories, and it is widely believed that Bosch was a respected and prosperous member of society, adhering to orthodox Catholicism. He was in high demand as a devotional painter, sought after by various patrons.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Hay Wain by Hieronymus Bosch, c.1516. Oil on panel, 135×200 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Hay Wain by Hieronymus Bosch, c.1516. Oil on panel, 135×200 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Mature Period

While other northern European artists focused on depicting biblical narratives, Bosch approached the same subject matter in a remarkably original and distinct manner that sharply contrasted with the prevailing harmonious Flemish style. He reimagined these stories through his vivid imagination, transforming religious parables into extraordinary fantasy realms filled with absurdity and rich ecclesiastical symbolism. It was during his loosely defined "middle period" that Bosch's iconic style began to emerge. His artworks featured contorted and distorted figures, vibrant colors, oversized and ominous foliage, as well as various devils and reptiles. In this period, he created works such as St. Jerome at Prayer (c. 1485-90), St. John the Baptist in Meditation (1490), and the altarpiece St. John on Patmos (1490-95), which might have been commissioned by the Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady.

However, it was the Triptych of the Adoration of the Magi (1494) that is often considered his first true masterpiece. Commissioned by Peeter Scheyfve and Agneese de Gramme of Antwerp, this work, depicting the Mass of Saint Gregory, solidified Bosch's reputation, even though it later deviated from his recognized style. As noted by Smith-Laing, "When Bosch died in 1516, he was already one of the most renowned painters of his time, and he soon became one of the most imitated and copied artists. By the 1530s... an entire school of painters in Antwerp emerged dedicated to that exact purpose, crystallizing Bosch's visionary image." Smith-Laing emphasizes that when "modern marketing professionals" became interested in Bosch's work, they primarily focused on him as a creator of hellish and diabolical imagery, often overlooking his quieter and contemplative works like the Adoration of the Magi.

Last period

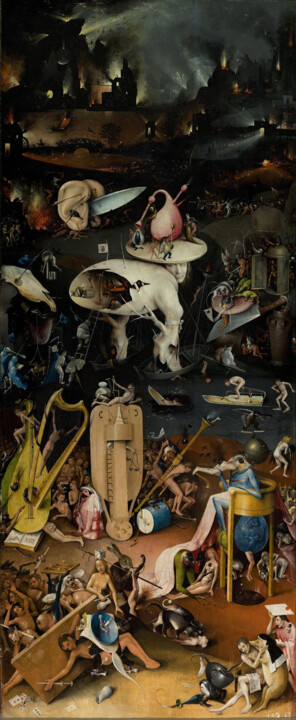

Undoubtedly, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510) stands as Bosch's most magnificent masterpiece and his most widely recognized work. In fact, for many people, this painting is the sole association they have with his name. At this point in his career, Bosch's style had reached its pinnacle, showcasing his mature artistic expression. The artwork depicts an earthly paradise where the creation and temptation of woman are juxtaposed with deeply unsettling and disturbing scenes of debauchery and hedonism.

The painting's dreamlike and nightmarish quality has taken on a legendary status, filled with numerous tiny naked human figures, distorted animals, and menacing creatures that seemingly emerged from the depths of the artist's boundless imagination. However, according to The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists, while works like The Garden of Earthly Delights possess an incredibly vivid imaginative power and incorporate intricate narratives and symbols, the underlying themes can be deceptively straightforward, often rooted in the popular culture of Bosch's era, including proverbs and devotional literature. The dictionary also points out that visually, the monstrous figures he painted bear resemblance to the peculiar creatures frequently found in the margins of medieval manuscripts and the grotesque gargoyles adorning Gothic architecture. In fact, even the cathedral in 's-Hertogenbosch contains notable examples of these gargoyles.

In addition to Bosch's preoccupation with the duality of good and evil in God's universe, he exhibits a remarkable ability for achieving compositional harmony and a meticulous attention to detail that rivals that of Renaissance painters. Renowned art historian E. H. Gombrich, referencing The Garden of Earthly Delights, remarked that Bosch had accomplished something unprecedented: giving tangible form to the fears that had plagued people's minds during the Middle Ages. This achievement was made possible by the combination of the lingering influence of old ideas and the artistic techniques provided by the modern spirit of the Renaissance.

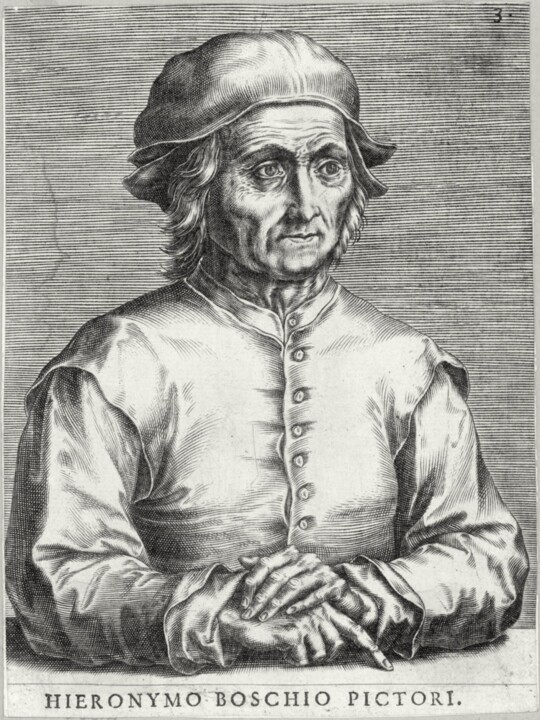

The Ship of Fools, believed to be originally part of a triptych, is widely regarded as a response to the publication of Sebastian Brant's immensely popular satirical book of the same name in 1494. Similar to Brant, Bosch employed the ship (actually a small boat) and its passengers as a metaphor for a morally corrupt society as a whole. The gathering of exuberant revelers once again demonstrates Bosch's association of sin with music, although it remains unclear why a monk and a nun are providing the musical entertainment in this particular scene. The ship's excessively long mast is topped with a large branch on which an owl perches, symbolizing sin, a recurring motif in Bosch's works. Some historians have speculated that the figure of the "Tree Man" in the Hell panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights was a self-portrait of the artist, but the only confirmed self-portrait is a drawing from 1508. This drawing, believed to have been created eight years prior to Bosch's death, may suggest the artist's awareness of his advancing age and the desire to establish his artistic legacy. The Brotherhood of Our Lady recorded that Bosch died in 1516, and a funeral service was held for him on August 9th at the Church of Saint John in 's-Hertogenbosch.

Despite his unquestionable place in art history, Bosch's body of work consists of only around 25 paintings and eight drawings. One reason for this limited output is attributed to the wave of destruction of artworks deemed immoral during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. Six of his works were acquired or confiscated by Philip II of Spain at the end of the 16th century (now housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid), while others emerged across Europe, resulting in a fragmented and incomplete historical record of one of the most extraordinary artists in history.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgment, c.1486. Oil on panel, 99×117.5 cm. Groeningemuseum, Bruges.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgment, c.1486. Oil on panel, 99×117.5 cm. Groeningemuseum, Bruges.

Works

Bosch created a total of at least sixteen triptychs, out of which eight have survived fully intact, while another five exist in fragmented form. His body of work can be divided into three periods: the early period (circa 1470-1485), the middle period (circa 1485-1500), and the late period (circa 1500 until his death). The majority of Bosch's surviving paintings, thirteen in total, were completed in the late period, with seven attributed to his middle period. Researchers from the Bosch Research and Conservation Project conducted dendrochronological investigations on the oak panels, leading to more accurate dating of most of Bosch's paintings.

In contrast to the smooth surfaces achieved through multiple transparent glazes in the traditional Flemish painting style, Bosch sometimes employed a sketchier approach in his works. His paintings featured rough surfaces with impasto techniques, deviating from the desire of contemporary Netherlandish painters to conceal brushwork and present their works as divine creations.

Although Bosch did not consistently date his paintings, he did sign some of them, although certain purported signatures are not authentic. Approximately twenty-five paintings attributed to Bosch remain today. In the late 16th century, Philip II of Spain acquired many of Bosch's works, leading to the Prado Museum in Madrid now housing notable pieces such as The Adoration of the Magi, The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (tabletop painting), and The Haywain Triptych.

Bosch primarily utilized oil as a medium to paint his works on oak panels. His palette was relatively restrained and consisted of common pigments available during his time. For blue skies and distant landscapes, he often employed azurite. Green hues in his paintings were achieved using copper-based glazes and paints made from malachite or verdigris, which were applied to depict foliage and foreground landscapes. As for the figures in his compositions, Bosch relied on lead-tin-yellow, ochres, and red lake pigments such as carmine or madder lake.

Hieronymus Bosch, Temptation of St Anthony, c.1500-1525. Oil on panel, 70×51 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, Temptation of St Anthony, c.1500-1525. Oil on panel, 70×51 cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Some interpretations

In the 20th century, as artistic tastes evolved, artists like Bosch gained greater acceptance in the European art scene. During this time, some argued that Bosch's art was influenced by heretical beliefs associated with groups like the Cathars or the Adamites, as well as obscure hermetic practices. This perspective found support in the fact that Erasmus, who had connections to the progressive religious atmosphere in 's-Hertogenbosch and the Brethren of the Common Life, shared similarities with Bosch in his critical writings.

On the other hand, there were those who continued an interpretation of Bosch's work that dated back to the 16th century, suggesting that his art was primarily intended to entertain and captivate, akin to the "grotteschi" of the Italian Renaissance. While earlier masters depicted the physical world of everyday experiences, Bosch presented his viewers with a realm of dreams and nightmares, where forms seemed to shift and transform. Felipe de Guevara, in one of the earliest accounts of Bosch's paintings, described him as the "inventor of monsters and chimeras". Similarly, Karel van Mander, an artist-biographer of the early 17th century, characterized Bosch's work as a collection of marvelous and peculiar fantasies that were often more unsettling than pleasant to behold.

In recent years, scholars have reevaluated Bosch's artistic vision and come to view it as less fantastical, recognizing that his art reflects the prevailing orthodox religious beliefs of his time. His depictions of human sinfulness, as well as his depictions of Heaven and Hell, are now seen as consistent with the moral teachings found in late medieval literature and sermons. It is widely accepted that Bosch's art was intended to convey specific moral and spiritual truths, much like other Northern Renaissance figures such as the poet Robert Henryson. His images are understood to have deliberate and precise symbolic meanings. Scholars, including Dirk Bax, suggest that Bosch's paintings often translate verbal metaphors and puns from biblical and folkloric sources into visual form.

However, the varying interpretations of Bosch's works raise significant questions about the nature of ambiguity in art from his era. In recent years, art historians have highlighted the presence of irony in Bosch's works, particularly in "The Garden of Earthly Delights," both in the central panel depicting delights and the right panel depicting Hell. They propose that this irony allows for a sense of detachment from both the real world and the painted fantasy world, appealing to both conservative and progressive viewers.

Joseph Koerner adds another layer to the discussion by suggesting that the cryptic qualities in Bosch's work stem from his focus on social, political, and spiritual enemies. The symbolism employed by Bosch is deliberately obscure, as it aims to conceal or harm these enemies.

A study conducted in 2012 suggests that Bosch's paintings also conceal a strong nationalist consciousness, serving as a critique of the foreign imperial government of the Burgundian Netherlands, particularly Maximilian Habsburg. According to the study, Bosch's use of layered images and concepts also reflects his own self-punishment, as he accepted well-paid commissions from the Habsburgs and their representatives, thus betraying the memory of Charles the Bold.

Debates on attribution

The exact number of surviving works attributed to Bosch has been a subject of much debate among scholars. Only seven paintings bear his signature, and there is uncertainty surrounding the authenticity of some works previously attributed to him. Copies and variations of his paintings began to circulate from the early 16th century onwards, and his distinctive style had a significant impact, leading to widespread imitation by his numerous followers.

Over time, scholars have progressively attributed fewer works to Bosch as advancements in technology, such as infrared reflectography, have allowed for deeper examination of a painting's underdrawing. Early and mid-20th-century art historians, such as Tolnay and Baldass, initially identified between thirty and fifty paintings as being by Bosch. A later monograph by Gerd Unverfehrt in 1980 attributed twenty-five paintings and 14 drawings to him.

In early 2016, after extensive forensic study conducted by the Bosch Research and Conservation Project, The Temptation of St. Anthony, a small panel housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, was credited to Bosch himself, overturning its previous attribution to his workshop. The Bosch Research and Conservation Project has also raised questions about the authorship of two well-known paintings, The Seven Deadly Sins in the Prado Museum and Christ Carrying the Cross in the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, suggesting that they may have been executed by Bosch's workshop rather than by the artist personally.

Top 5 artworks

Hieronymus Bosch, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, c. 1500. Oil on wood, 120cm × 150cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, c. 1500. Oil on wood, 120cm × 150cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (c. 1500)

Continuing his exploration of the Last Judgement theme, Bosch's painting portrays the Seven Deadly Sins individually arranged around a central circle with Christ emerging from a tomb. The Four Last Things—Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell—occupy the corners. Below Christ, a text warns, "Beware, beware, the Lord sees." A banderol at the top quotes Deuteronomy 32:28, emphasizing the foolishness of those who lack understanding, while the banderol at the bottom cites Deuteronomy 32:20, indicating God's turning away from them. Stepping back from the painting reveals its symbolism, with a large central circle representing Jesus as the all-seeing eye of God, surrounded by a smaller circle depicting the Seven Deadly Sins.

The depiction of the Last Things reflects the stages the soul is believed to go through after death. For instance, "Death" portrays a dying man receiving his last rites while a skeleton, a devil, and an angel await his passing, symbolizing the final death blow, the struggle for his soul, and the afterlife. In "Heaven," an angel protects a woman from a devil, with Jesus and his angels awaiting the arrival of the righteous. Within the circle of the Deadly Sins, scenes like "Wrath" show feuding peasants attacking each other, "Envy" depicts a woman tempted by a rich man as her envious parents look on, and "Pride" features a vain woman admiring herself in a mirror held by the devil.

The painting is housed in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, which displays it as an original Bosch artwork. However, there is some debate surrounding its attribution, although it is generally agreed that it was created in his workshop. The painting bears Bosch's name, but there is evidence suggesting that a pupil may have contributed to it, possibly adding Bosch's name out of respect or to enhance its value. Considering the uneven quality of the painted figures and the resemblance to Bosch's later works characterized by a wide brush technique, such as The Haywain Triptych, the Museo del Prado suggests that Bosch painted some scenes while an apprentice worked on others.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Haywain Triptych, ca. 1516. Oil paint on oak panels, 135cm × 200cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Haywain Triptych, ca. 1516. Oil paint on oak panels, 135cm × 200cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

The Haywain Triptych (c. 1512-15)

The outer doors of the triptych display a vibrant and colorful scene known as the "Pilgrimage of Life," deviating from the earlier grisaille style typically seen in Bosch's outer panels. Art critic Ingrid D. Rowland interprets the figure on the exterior panels as an everyman, representing the challenges faced in one's physical and spiritual journey through life. It is emphasized that constant faith and vigilance are necessary to navigate the treacherous road of existence. This theme of pilgrimage and the potential dangers of life foreshadows the unfolding narrative of sin in the three inner panels.

The first inner panel depicts the expulsion of disobedient angels from the Garden of Eden as a punishment for their sins. These rebel angels undergo a metamorphosis into insect-like figures, echoing the imagery in the first panel of The Last Judgment. The central panel portrays humanity's descent into a sinful world under the watchful eye of Christ, the Redeemer. At the bottom of the frame, honest and humble workers and parents are contrasted with those consumed by greed, frantically grasping at hay while oblivious to the fact that the hay wagon is being driven by devilish chauffeurs straight into Hell. In the final panel, Bosch presents his unparalleled vision of Hell, which is depicted as still under construction. The devil's builders are busy constructing a circular tower while the devilish wagon drivers deliver sinners to their new abode.

Art historian Pilar Silva interprets the piece as an illustration of how humanity, regardless of social class or origin, becomes possessed by desires for material possessions, making themselves vulnerable to deception and seduction by the Devil. Bosch suggests that renouncing earthly goods and sensual pleasures is necessary to avoid eternal damnation. The painting offers a different type of exemplum, as it focuses not only on doing good but also on avoiding evil and adhering to this principle throughout life. While most scholars interpret The Haywain Triptych in religious and moralistic terms, art historian Wilhelm Fränger proposed an alternative theory, suggesting that these "sinner" triptychs were commissioned by a mystery cult rather than the Catholic Church.

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1485-50. Oil on panel, 138cm × 144cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1485-50. Oil on panel, 138cm × 144cm. Prado Museum, Madrid.

The Adoration of the Magi (c. 1494)

Bosch's triptych provides an early glimpse into the artist's brilliantly original and morally complex vision, as depicted through the story of the Three Kings (or Magi) adoring the Christ child. The naked infant Jesus sits on the Virgin Mary's lap, while the Magi approach with regal dignity. Art historian Pilar Silva notes the influence of Jan van Eyck in the portrayal of Mary and Jesus, while Bosch showcases his painting skills in the luxurious robes and offerings of the Magi. His masterful use of fine brushstrokes to create highlights gives the appearance of delicately drawn details.

In contrast to typical fifteenth-century Epiphany narratives, Bosch's painting includes irreverent and curious peasants or shepherds (representing the Israelites). They stand as onlookers, peeking from behind a damaged stable wall or even from the rooftop.

One of the most distinctively "Boschian" elements in the painting is the bearded figure standing inside the stable, behind the Magi. Silva describes him as the Antichrist, dressed in a cloak that barely covers his body and with a transparent veil underneath. The figures inside the hut with him, including a woman resembling Leonardo's caricatures and sporting a headdress similar to demons in Bosch's works, exude a grotesque and sinister expression.

In the landscape, Silva identifies a house with a flag depicting a swan and a dovecote above, indicating it is a brothel. She also notes a man pulling a horse ridden by a monkey, symbolizing lust, moving toward the brothel. The sense of menace in the painting is further reinforced in the middle distance, where two armies on horseback charge. Identified as Herod's soldiers in oriental headdresses, they are portrayed as searching for Jesus to kill him. The city on the horizon represents Bethlehem, and Bosch indulges his imagination by giving the buildings an oriental appearance, with a windmill positioned just outside the city walls.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgment, c. 1482. Oil-on-wood triptych,163.7cm × 242cm. Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Last Judgment, c. 1482. Oil-on-wood triptych,163.7cm × 242cm. Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna.

The Last Judgment (1482-1505)

In the medieval church, the concept of the Last Judgement held a prominent place, instilling in believers the belief that if even God couldn't prevent them from sinning, the fear of eternal damnation in the fires of Hell certainly would. This narrative was reiterated in numerous sermons and books, but Bosch's unique vision always presented it as an apocalyptic scenario. The World History of Art encyclopedia highlights a comparison between Bosch's treatment of the creation of Eve and Michelangelo's composition in the Sistine Chapel, noting that while both works were created around the same time, they evoke very different feelings. Bosch, reflecting the declining era of the Middle Ages in northern Europe, had a strong sense of the reality of hellfire, while Michelangelo, during the flourishing High Italian Renaissance, emphasized the human aspect of the story.

This particular work, incidentally Bosch's largest, showcases the artist's distinctive raised impasto brushwork, challenging the prevailing technique of Flemish painters who favored transparency and a smooth application of paint. Here, Bosch's fetid imagination is fully on display, featuring his fascination with the theme of metamorphosis, such as angels transforming into insects, a woman with lizard-like legs, a mouse turning into a porcupine (or vice versa), and a grotesque hag roasting humans on a spit. Unlike many of his other works, however, this triptych focuses solely on Heaven and Hell, neglecting to depict an intermediary place like purgatory, where souls traditionally had the opportunity to reflect on their actions before their ultimate fate of salvation or damnation was determined.

Interpretations of Bosch's art vary, with some suggesting that he was influenced by heretical ideas, others proposing that he channeled the prevailing anxieties of his time, and still others considering him a "populist" or entertainer who presented one of the Bible's greatest moral tales from an absurdist perspective (a view particularly favored by the Surrealists). Regardless of the interpretation, the World History of Art emphasizes that the familiar story depicted in Bosch's works would have been readily understood and the underlying message believed by both illiterate peasants and educated burghers of the time. However, it acknowledges that some of Bosch's images must have been unsettlingly new and distressing, possibly even evoking feelings of despair.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490-1510. Oil on oak panels, 205.5 cm × 384.9 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490-1510. Oil on oak panels, 205.5 cm × 384.9 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid.

The Garden of Earthly Delight (1490-1510)

Bosch's most renowned artwork was commissioned to celebrate the wedding of the daughter of Count Henry II of Nassau, Brussels. The triptych aimed to depict the "benefits and hazards" of marriage through a biblical parable. The left panel portrays Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, while the center panel depicts a hedonistic "paradise." The right panel presents a vivid depiction of a blazing Hell awaiting sinners and the unrepentant. On the outer case, Bosch showcases the origin of the world, specifically the third day of creation when the earthly paradise was formed, in grayscale tones. A small figure of God with an open book is depicted in the upper left corner, accompanied by the Latin inscription, "For he spoke, and it came to be; he commanded and it stood firm."

In the Garden of Eden scene, a youthful God presides over the marriage of Adam and Eve. The heavenly surroundings are filled with animals, mythical creatures, trees, water, and a fantastical structure floating on the lake. Art historian Wilhelm Fraenger notes the physical contact between God, Eve, and Adam, creating an inseparable connection through which divine power flows, forming a complex of magical energy. From this perspective, the scene visualizes the divine union between man and God. In the center panel, Bosch illustrates the progression of the Garden of Eden and the development of humanity through joyful celebrations and pleasurable activities. Once again, fantastical creatures, plants, structures, and organic pods surround the figures.

The nudity of the figures indicates that the scene takes place prior to the expulsion from paradise. However, their focus on instant self-gratification and succumbing to temptation (symbolized by the recurring motif of the strawberry) foreshadows the final judgment and descent into Hell. Bosch presents a dark and chaotic landscape devoid of flora and fauna. The numerous musical instruments likely symbolize various forms of sin, with bagpipes representing lust and sensual pleasures. Standing at the center of the scene is his iconic "tree man," possibly a self-portrait, observing the world much like the artist himself.

The Garden of Earthly Delights has inspired a wide range of interpretations over the centuries. It has been described as a satirical commentary on the sinful nature of humanity by seventeenth-century Spanish historian José de Siguenza, and in the twenty-first century, art historian Pilar Silva viewed it as a reflection on the transient nature of earthly vanity. Art historian Claire Selvin beautifully summarized the piece, highlighting Bosch's penchant for humor and absurdity. She emphasized the contorted and acrobatic poses of the nude figures, the participation of birds and animals in the erotic revelry, and the presence of snug shells and enclosures in various shapes and colors. Even in the macabre scenes of destruction on the right side of the triptych, levity can be found, with giant ears wielding knives and monumental musical instruments serving as torture devices. More than 500 years after its creation, The Garden of Earthly Delights continues to captivate and entertain art historians and art enthusiasts alike, showcasing Bosch's limitless imagination.

Legacy

Throughout Bosch's lifetime, his artworks were collected in various European countries, earning him widespread admiration and inspiring numerous students and followers. Notably, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, nicknamed the "Second Hieronymus," was greatly influenced by Bosch's approach to painting landscapes. While interest in Bosch's work declined in the centuries that followed (except in Spain), he experienced a resurgence in the modern era. His influence extended to the Surrealist movement and artists like Max Ernst, René Magritte, and particularly Salvador Dalí, who even claimed that Bosch was the first modern artist. The distinctive rock formation resembling Dalí's face in his famous painting, The Great Masturbator (1929), was inspired by a similar formation found in the left panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights. Leonora Carrington, after encountering Bosch's works at the Museo del Prado in 1939, also drew inspiration from his renowned compositions. In her artwork The Giantess (1947), Carrington incorporated hunters in an uncanny landscape featuring winged fish and seafarers floating in an ocean-like sky, reminiscent of the landscapes depicted by Bosch.

Art critic Alastair Sooke highlights the enduring fascination with Bosch's work, particularly due to its apocalyptic tone that resonates in the context of global conflicts and international terrorism. References to Bosch's art can be found in various forms of media, including films, television shows, video games, books, and even fashion collections. Art critic Tim Smith-Laing adds that few, if any, of Bosch's contemporaries can claim such sustained fame. His artworks continue to attract large audiences in museums, and his influence extends far beyond traditional mediums, with his imagery appearing on items ranging from books, T-shirts, and postcards to accessories like tote bags, mousepads, and phone cases. There are even Dr. Martens boots featuring prints of his artwork.

Summary

Arguably the most exceptionally innovative and morally intricate religious painter in northern Europe, Bosch is primarily associated with artworks that possess a disturbingly vibrant and dream-like quality. Despite the limited number of approximately 25 surviving original pieces, the nightmarish symbolism depicted in his paintings is immediately recognizable as distinctly "Boschian" and has become a prominent feature of the grotesque genre. While Bosch is undoubtedly considered an iconoclast, some historians have proposed that beneath his unsettling imagery, the artist was, in fact, a profoundly traditional figure. Contrary to a troubled mindset, he demonstrated a capacity for subtlety and complemented his grotesque compositions with meticulously crafted decorative and devotional works that embodied his deeply rooted Christian beliefs.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei