Poised at the edge of Milton Keynes’ Modernist city plan, 6a Architects’ extension of the MK Gallery rekindles a lost arcadian vision

Milton Keynes is a place made of contradictions. A social democratic dream implemented under Thatcherism, it is quintessentially English but feels North American, verdantly pedestrian yet utterly devoted to the automobile. Sniffed at and unfamiliar to Londoners, yet a source of pride to its residents, MK is home to some of both the richest and poorest areas of the United Kingdom, a testament to rationalist planning that harbours a surreal sense of weird Englishness within it.

‘Milton Keynes is the product of a very directed and determined effort where design was seen as having a very direct public good’, suggests Tom Emerson, cofounding director along with Stephanie Macdonald of 6a Architects, whose extension of the MK Gallery has just opened – the first cultural building to be built in Milton Keynes since the original gallery and adjacent theatre were constructed by LCE Andrzej Blonski Architects in 1999. As chief architect of Milton Keynes between 1970 and 1976, Derek Walker often dabbled in some of the more outré ideas of British architecture at the time, and indeed Archigram built their only free-standing building there in 1973, a play centre. More sensible work, such as the expansive elegance of the 750m-long Miesian shopping centre completed in 1979, is rightly celebrated, and in the early years a who’s who of young architects were involved in providing the buildings for this new endeavour, with work often tentatively reaching towards what would later become High-Tech.

The 1974 AD cover reveals the Modernist grid of Central Milton Keynes

The 1974 AD cover reveals the Modernist grid of Central Milton Keynes

19. helmut jacoby, milton keynes in 1990, 1971 (c) estate of helmut jacoby web

An aerial view of which was drawn by Helmut Jacoby in 1974. Image © Estate of Helmut Jacoby

The architecture of this vision was ambitious but always compromised. Over the years Milton Keynes has acquired a particular public image, that of the ultimate suburb: a quarter of a million people an hour from each of London, Oxford and Cambridge, living in a perfectly agreeable environment with no identity of its own. Car tyres wear out asymmetrically because of all the roundabouts, concrete cows are the only culture (the original MK Gallery and Theatre were built following a 25-year campaign by local residents fed up with the city’s lack of cultural infrastructure), and there’s nothing for young people to do but leave. This is obviously unfair, but it is indeed true that MK, the biggest of the British New Towns, designated in 1967, has a distinctly dispersed character. Planned according to the concept of ‘non-place urban realm’ – Melvin Webber’s theory of automobile urbanism derived from Los Angeles – MK’s expansive and now somewhat dilapidated granite public space presents a very low-pressure version of urban life.

‘This world may be perceived today as a last gasp of a more social vision of collective enjoyment’

Some architects built very difficult work: the Grunt Group’s Netherfield in 1971 or Norman Foster’s Beanhill from 1975 are instances of the last of the original batch of Modernist housing failures, technically problematic and urbanistically flawed, and now among the most deprived areas of the UK. Later, beginning in the 1980s, the continued expansion of MK began to rely more fully on the private sector, and the remaining patches of the ‘roundabout city’ grid plan – which to this day remains remarkably intact – were mostly filled with cul-de-sac housebuilder product, easy to sell but socially myopic.

‘Of course not everything came to pass with the changing politics of the time’, Emerson continues. ‘But we wanted to respond and maybe even recover some of the determination and optimism.’ Previously contained in two original ’90s small box volumes, MK Gallery is entered from the small square shared with the Milton Keynes Theatre. Praised at the time by Jonathan Glancey for being ‘thoughtful’ and ‘unpretentious’, its wavy roof and crude portico speak more now of just how lost British architecture could be during the New Labour years.

MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, by 6a. Image by Johan Dehlin

The neon heart of the City Club art project reflects the original logo for MK. The town’s signature porte-cochère signals the gallery entrance

Milton Keynes architecture office, aka the Custard Factory, designed by Norman Foster

MK’s architecture office, aka the Custard Factory, was designed by Norman Foster in the early 1970s and inspired the colour palette in the café. Photograph by John Donat, courtesy of RIBA Collections

6a’s contribution transforms these existing buildings but also extends to the north, putting some distance between the gallery and the theatre. ‘We decided quite early to make the largest amount of space the budget would allow’, explains Emerson. The ‘steel-framed box dressed for the occasion with a gridded reflective suit’ is made up of folded and polished stainless-steel panels, shimmering and visually absorbent of their surroundings. Gently projecting profiles mark out a quintessentially MK grid across the facade, into which a few prominent and carefully placed picture windows are arranged. To one side, a silver cylindrical escape staircase is partially detached from the building, completing what Emerson calls ‘a fairly resilient composition which can respond easily to contractions and expansions’.

The gallery sits at the end of Midsummer Boulevard, a name with suitably pagan overtones and the axis of the most emphatically gridded core of the town running from the train station and its piazza in the south to the north-eastern edge of Central Milton Keynes. MK Gallery occupies the last prominent site before the town centre abruptly cuts off and the rolling contours of Campbell Park begin, a bucolic view that is revealed in the top-floor auditorium through an enormous, 12m-wide semi-circular window.

Downstairs, the architects have added two further exhibition spaces to the original gallery, more than doubling its floor area. The openings between rooms have shifted to form an enfilade, creating a view through the building from the front elevation out to the other side and beyond to the park.

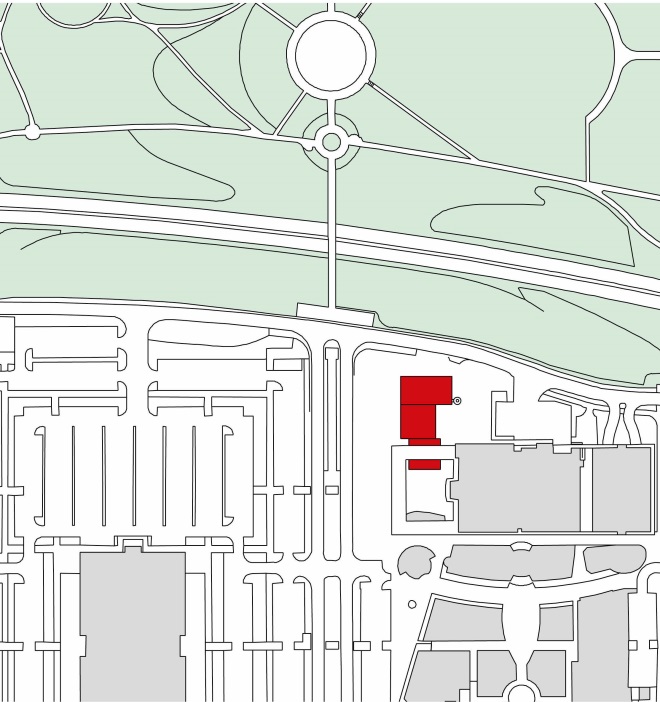

Mk site plan2

The building is tightly woven together with a public art project called City Club, by artists Gareth Jones and Nils Norman, and designer Mark El-khatib. Taking as its starting point the ludicrously ambitious community and leisure centre of the same name that was planned for MK, but which remained unbuilt, City Club investigates concepts of Modernist play, with the artists asking ‘what would happen if the public art of a city swapped places with the infrastructure?’

City Club manifests itself through a series of gestures: a neon heart, the original logo for Milton Keynes, has been placed on the facade, while one of the town’s signature porte-cochère structures fronts the entrance. Elements have been utilised from the original Infrastructure Pack, which defined street furniture, signage and play equipment for the new settlement, and planting and public artworks extend the historic lineage. Signage and graphics play an important role too – rounded ’70s typefaces and other such iconography abounds, while most significantly a colour scheme called City Club Colour Chart runs through the entire project.

‘6a’s new building provides a permanent reminder of the radical heart of this most suburban of environments’

Divided into two sets, a set of saturated neon colours represents ‘downtown’, while a more pastoral set of greens, blues and browns represent the landscape. The colours are found throughout the building: the key-clamp scaffolding in the café, previously the gallery’s loading bay, is decked out in brash red and yellow and harks back to the Foster’s original MK architect’s office, while in the auditorium a floor-to-ceiling curtain is striped by the landscape’s full colour spectrum. Elsewhere the colours appear in the bathrooms and vertical circulation, including some extremely orange lifts.

‘It may be a response to a context that is missing – or incomplete – as much as one that is present’, says Emerson. Certainly, the building knowingly plays with a certain aesthetic of mid-’70s: over-saturated, airbrushed visions of leisurely life, all plastics and bell-bottoms. One might worry that riffing on this aesthetic is a little too Instagram- friendly, perhaps, but the mood is definitely present in the air beyond the more obvious visual stimuli. This world was created by 1960s optimism feeding out into the mainstream, but perhaps may be perceived today as a last gasp of a more social vision of collective enjoyment.

‘I hope it has some of the “can-do” spirit of the modern American condition,’ Emerson confesses, ‘but it is laid over Buckinghamshire, not far from Stowe, so can never totally escape the English condition.’ Milton Keynes’ vision of planned arcadia presents to us today a unique and rather melancholy vision of what Britain might have become if it hadn’t succumbed to the twin perils of laissez-faire and imperial nostalgia: a technologically advanced nation comfortable with its own modernity. 6a’s new building provides a permanent reminder of the radical heart of this most suburban of environments.

MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, by 6a. Image by Iwan Baan

Photograph by Iwan Baan

MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, UK

Architect: 6a Architects

Artists: Gareth Jones, Nils Norman, Mark El-khatib

Structural engineer: Momentum

Landscape architect: JCLA

Photographs: Johan Dehlin unless otherwise stated

This piece is featured in the AR May 2019 issue on Periphery – click here to purchase your copy today

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design