Light matters, a monthly column on light and space, is written by Thomas Schielke. Based in Germany, he is fascinated by architectural lighting, has published numerous articles and co-authored the book „Light Perspectives“.

From early nocturnal studies in a lonely hotel room to transforming a volcano in the world’s biggest landscape art project to, most recently, lighting up the Guggenheim in New York, the American artist James Turrell is driven by his fascination with light. He explores perception for visual experiences where light is not a tool to enable vision but rather something to look at itself.

More Light Matters, after the break…

Since 1972 James Turrell has been transforming the “Roden Crater” into a monumental work of art. Located under the blue sky of northern Arizona, the natural volcano is converted into a revelation of celestial phenomena: the sun, moon and stars. For Turrell, the “Roden Crater” is dedicated to the sky: “I am not an “earthwork” artist. I am totally involved in the sky. Let me make this very clear: the main thing is that I am totally interested in space and not in form.”

To heighten the light experience of a uniform blue sky, Turrell erases the gradation near the horizon; as he states: “…if you go to the Rocky Mountains, to a high altitude where it is cold, you see sky that is such a crisp blue you feel that you could cut it and put it in cubes! That is the kind of sky I want, and I have been able to get it by selecting the altitude. There are gradations near the horizon where the blue is lighter, and then gradually, toward the zenith, it gets deep. With Roden Crater I have taken out the first fifteen degrees of height by aiming the tunnel sight lines above that level. At that point you see thirty degrees less than one hundred eighty degrees. That is how you get that incredible color – by eliminating all of the white at the horizon.”

As Jan Butterfield explains in his book about light art, in his crater project, Turrell has created special rooms for the sunrise, sunset and the moon, providing for astronomical events for the next two thousand years. However, only very few people will have the chance to encounter these spectacular moments due to the small numbers of visitors allowed per day and the rare nature of celestial constellations, like the 18 year cycle for the moon appearing in the center of the crater tunnel. Concurrently, a camera obscura effect will cast a moon image on the back wall of the tunnel.

Turrel's inspiration for his ascetic, colourful and very private works is drawn from his parents, who were Quakers, and his studies in psychology and mathematics. An enlightening moment in his life occurred in his undergraduate art history class at Pomona College whilst watching a slide projector in the darkened room. He started an inquiry in which light is not a tool to enable vision but an element to look at.

In the 1960s Turrell started to work solely with light. He closed the windows of his white laboratory and only allowed a few small openings through which the light could pass. Viewed at night, the light and the colour originated from outside stoplights, headlights, and traffic signals. Turrell has never applied any body colour in his work. His installations only involve coloured light inhabiting a space, which Turrell explains as follows: “If the color is in the paint on the wall, then in making a structure and allowing light to enter it, the color will tend to ride on the walls. But if the color of the wall is white, which in one way is noncolor, the the light is allowed to enter the space riding on the light, and that color has the possibility of inhabiting the space and holding that volume rather than being on the wall.”

A second aspect from the “The Mendota Hotel Stoppages” night installation became highly relevant for his future work as well: Light from the outside shaped the character of the interior space for the viewer. In the Mendota project it was the urban traffic, but in many other projects the outside sky is framed for the light experience in the viewer room.

In one of his other early installations, Turrell used a high-intensity projector to cast a tightly framed beam of light in the corner of the room and generate a geometric form with the illusion of a three-dimensional figure. For Turrell, this project was a step towards creating physical presence with light: “What happened then is that I got more interested in the plumbing of hypothetical space and the idea of the presence or quality of light. Afrum … was more of a painting in the sense that you have painting on a two-dimensional surface that alludes to perhaps three dimensions or unsolvable three-dimensional things. This work was about taking three-dimensional space and making the same kind of allusions to the space beyond that – you don´t need to call it fourth dimension but just one that does not solve up in three. So in that way, my work does have a lot more to do with painting than it does with sculptural or architectural senses, because the first thing that is important is that the light is used as material, and that it has a physical presence as such, and that space is solid and filled and never empty.”

After the projection installations Turrell gradually moved towards more architectural situations and experimented with shallow space constructions. The hidden diffuse light makes them fascinating. Back lit partition walls create a floating and soft perspective for the viewer. In other space division constructions Turrell has installed a window-like opening between two rooms where the diffuse light of the outside space pours into the unlit viewing space. These windows emerge as a passage for a vertical diffuse sky. Invisible edges due to round corners in the outside room, a dissolved back wall texture due to the diffuse light, and an optical defocusing trick with the clear window frame in the foreground as well as the diffuse wall in the back, merge into an overwhelming experience of infinite luminescence.

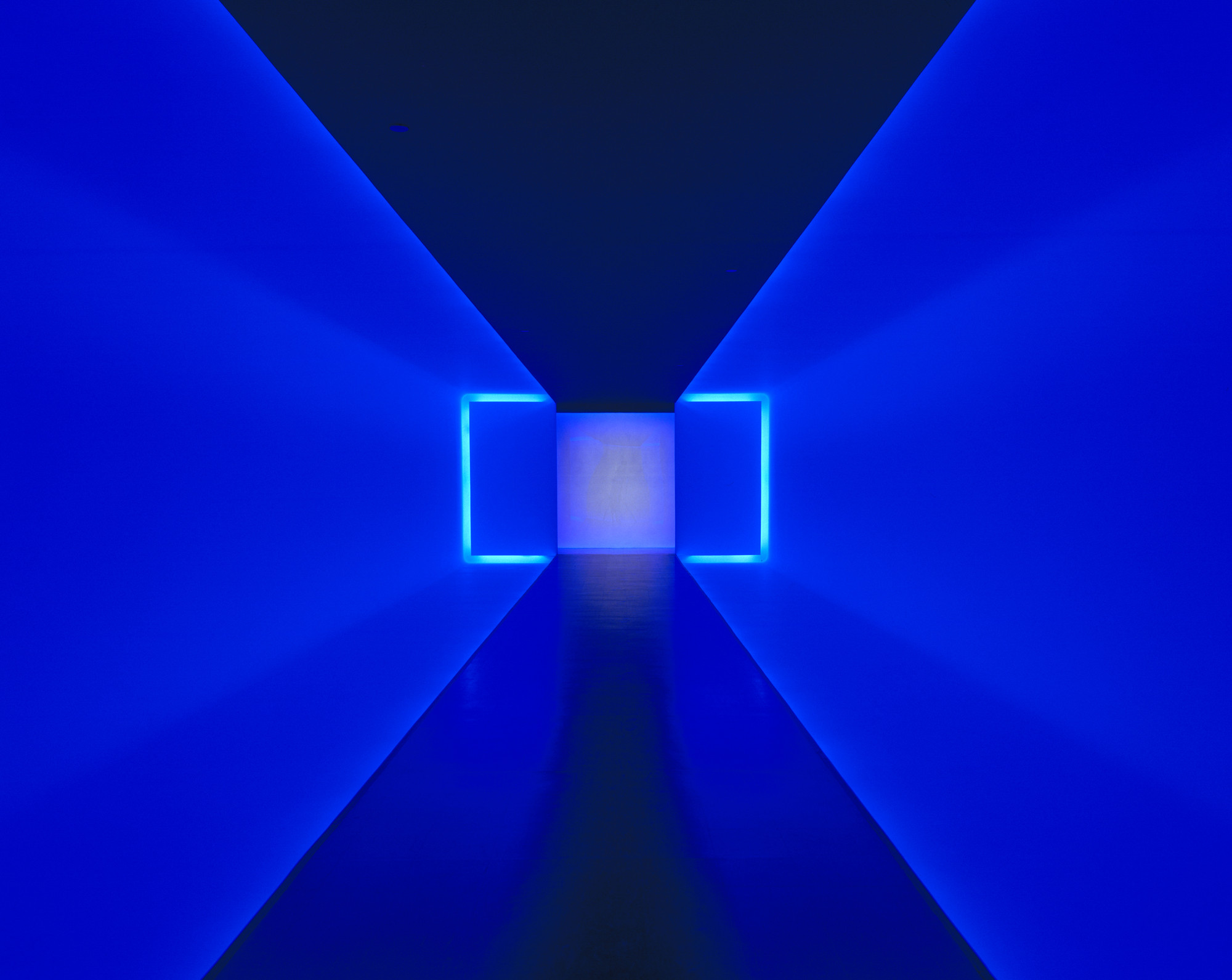

In comparison to Turrell’s abstract shallow space installations, his tunnel installations involve a stronger architectural context. Precise frame lines are set in contrast to diffuse blue light in order to let the viewer experience transcendental passages playing with the boundaries and elements of the sky.

The blue light has a fascinating perceptual advantage for Turrell, because the human eye perceives an environment within the blue light spectrum as less focused. Additionally, the chromatic aberration causes a defocusing effect for blue light when red and green are in focus. Therefore blue illuminated walls and surfaces appear more diffuse and immaterial compared to other colours. With blue light Turrell has a powerful tool to dissolve the focus for his aesthetic programme: “There is no object in my work. There never was. There is not image within it. I have: no object, no image, no point of focus. My interest is in plumbing the space.”

In parallel to the Roden Crater project based on natural light, the light artist turned to large architectural installations with electrical light. In these works he also has the chance to include and programme dynamic colour changes. Turrell developed a fascination for vibrant colour in art school, when he was intrigued by Mark Rothko´s field paintings.

For example, the Wolfsburg Bridget's Bardo installation appeared like a spiritual passageway to heaven. Walking down the long ramp all architectural edges dissolve, leading to a homogenous light field. “Light itself is becoming the revelation,” as Turrell declared. Slow transitions of blue and magenta shades enveloped the viewer in the powerful light observatory.

Another large interior installation can soon be visited in the rotunda of the New York Guggenheim Museum, opening on the summer solstice on June 21st. The project „Aten Reign“ will draw away the attention from the built environment and toward the interior as a space of light. The rotunda will only be experienced from below – not as an open void to be looked across, to emphasize the sky perspective. Daylight will enter from the oculus down to several layers of a massive assembly suspended from the ceiling of the museum. Five elliptical rings with coloured light will surround the core daylight eye. Again, the technical infrastructure will be mostly hidden from view to focus on the visual perception and not the light technology and the constructive details. This installation once again underlines Turrell´s light perspective: “My art is about your seeing.”

Several exhibitions offer you the opportunity to encounter the work of James Turrell in America this year and next year in Europe: Los Angeles County Museum of Art (May 26, 2013 – April 6, 2014), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York (June 21, 2013 – Sept 25), The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (June 9, 2013 - Sept 22), and Kayne Griffin Corcoran in Los Angeles (May 25 – July 20, 2013).

As part of the Google Art Project’s new series of art talks, curators from the three mayor concurrent James Turrell exhibitions on view this summer will be responding to crowd-sourced questions about the artist on July 9, 3pm EDT. Viewers can access the talk via Hangouts on Air on the Google Art Project’s Google+ page.

The James Turrell retrospective exhibition will also travel to the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edingburgh/UK (Summer 2014), Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich/UK (2014), in The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (September 2014), the Israel Museum in Jerusalem (June 1-October 18, 2014) and the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra (December 2014-April 2015), and probably as well the Sprengel Museum in Hannover (Spring 2014). Visitors to Argentina may enjoy a trip to the permanent James Turrell Museum located in the Provincia de Salta.

For further reading:

The Turrell quotes derive from the book “The art of light + space” and the press release by Kayne Griffin Corcoran.

Light matters, a monthly column on light and space, is written by Thomas Schielke. Based in Germany, he is fascinated by architectural lighting, has published numerous articles and co-authored the book „Light Perspectives“. For more information check www.arclighting.de or follow him @arcspaces