1.1a 6 mph Woonerfs [Lindsey Vazquez and Erin Dillmann]

Introduction

The Dutch word woonerf (plural woonerven) translates to living street or place. In the 1960s and 1970s, Niek de Boer and Joost Váhl first developed the woonerf concept in the city of Delft, the Netherlands. A woonerf is a residential street where pedestrians, motor vehicles, and bicycles share the street at slow, safe speeds for all participants involved. In the woonerven’s home country, traffic regulations prohibit speeds greater than 15 km/h (9.3 mph) within the street. The strategic design of the street utilizes physical barriers to discourage “rat-running” (cut-through traffic) and reduce motor vehicle speeds to the desired safe speeds for the neighborhood. The systematic safety features implemented characterize a street that is safe for pedestrians across its entire width. The woonerven studied were Westerstraat area, one of the first woonerven, and Tanthof, a woonerf built in the 1980s.

PICTURES FROM JEFF: Historical pictures of woonerven in the 1970s when they were first built.

Woonerven in the Netherlands

Map: Locations of Westerstraat and Tanthof. The pink area to the north is the Westerstraat woonerf, located behind the train station, which was retrofitted to be a woonerf. The green area to the south is Tanthof, a woonerf built in the 1980s.

In the Netherlands, woonerf neighborhoods can have pedestrians, cyclists, and cars share the same space because the speeds are low enough that cars do not pose a threat to cyclists and pedestrians. The original purpose of these streets was to provide an extension of the home for those who could not afford a single-family home in a neighborhood with a big back yard. A woonerf provided a guaranteed safe space for the children of the neighborhood to play in the street and within view of the home’s front facade. With all the children playing in the street, woonerven also provided a sense of community throughout the neighborhood. Parents and children alike would meet in the street to socialize un-interrupted by frequent motor vehicle traffic. Residents began to value their streetscape and plant flowers and paint murals to beautify their living space. Although this was the original intent of a woonerf, it can also be seen as a great example of traffic calming for a residential neighborhood.

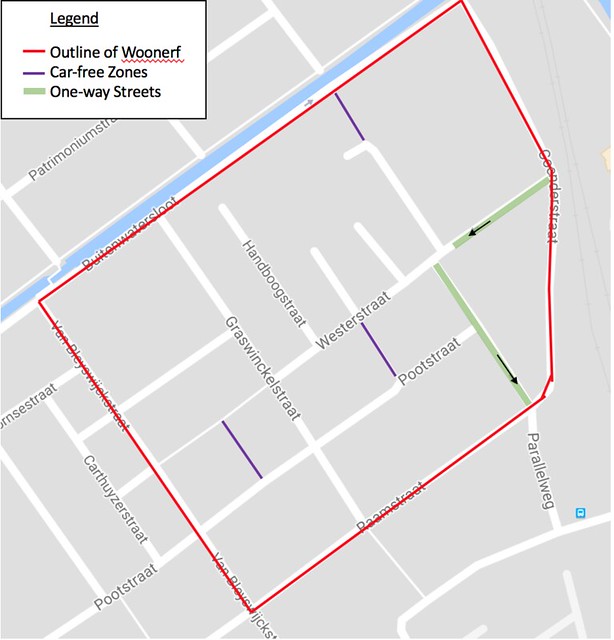

Traffic calming was achieved in these small neighborhoods with a combination of methods including lowering speeds, removing cut-through streets and adding dead ends, and reducing the available driving width of the roadway. In Westerstraat, the only straight cut-through street, Graswinckelstraat, contains many speed humps and is narrow so that cars drive cautiously and at lower speeds making it an undesirable route for rat-running (Figure 1). The other neighborhood streets that were originally cut-through routes were converted to one-way streets in the opposite direction, creating a dead end for the motor vehicle or a bike priority path. This design makes it more convenient for motor vehicles to use designated cut-through roads instead of attempting to travel through the woonerf. Using these traffic calming techniques, the woonerf is an effective network for bikes and pedestrians, but not for cars.

Figure 1: Westerstaat Woonerf. The lack of available cut-throughs and one-way streets causes drivers use main roads, unless their destination is in the woonerf.

Tanthof, unlike Westerstraat, does not have one-way streets as a way to discourage through traffic (Figure 2). Tanthof was originally planned as a woonerf; therefore, designers deliberately designed the neighborhood with no cut-through streets for motor vehicles. Instead, the neighborhood contains numerous one-way streets, dead ends and bike only paths.

Figure 2: Tanthof Woonerf. Similar to Westerstraat, drivers will not use the road as a cut-through because there is no available cut-through. The designers eliminated cut-throughs by creating pedestrian and cyclists only zones.

Features of a Woonerf

Visible Entrances

Woonerven are known as “livable streets” and are often identified as such with a blue sign identifying the street’s priority users in order of importance; pedestrians, children at play, the neighborhood, and cars (Figure 3). Every other street in the Netherlands is not identified this way. This sign is used in tandem with the visible change in pavement from black asphalt to red stamped asphalt to indicate the change in street zone and encourage caution while driving.

Figure 3: Entrance to a woonerf. The blue sign puts people and the houses in the foreground, signifying to drivers that the main users of this space are the residents. (Should we put this in the annotation of the picture and get rid of it in the caption?)

Physical Barriers

In addition to the lack of available cut-throughs, woonerven feature other traffic calming measures such as chicanes, narrowing streets, and speed humps to achieve low speeds for people, cyclists, and cars to comfortably share the road. Chicanes, or curves/wiggles in the street, require drivers to slow down as they maneuver around the curve or obstacle. Westerstraat uses alternating parking on each side of the street and boxed planters to imitate the function of a chicane (Figures 4 and 5). Westerstraat’s existing streets were mostly straight because Westerstraat was retrofitted as a woonerf after its construction and its original purpose was to provide a direct route through the neighborhood.

Figure 4: Chicanes in Westerstraat created by alternating parking

Figure 5: Chicanes in Westerstraat created using box planters

Conversely, Tanthof, which was originally designed as a neighborhood of woonerven, had chicanes built into the street design to discourage drivers from speeding (Figures 6 and 7). The planners were able to incorporate these chicanes in the design because they built Tanthof from scratch. Westerstraat had to rely on parking and boxed planters to create chicanes because they had to retrofit existing streets to create the woonerf.

Figure 6: Chicanes in Tanthof created by curves in the road

Figure 7: Chicane at an intersection in Tanthof

It is also important to note that in Tanthof there was more space for parking and most of the parking was angled compared to the parallel parking in Westerstraat. Since Tanthof was designed as a woonerf, it was likely easier for the planners to designate more space to cars.

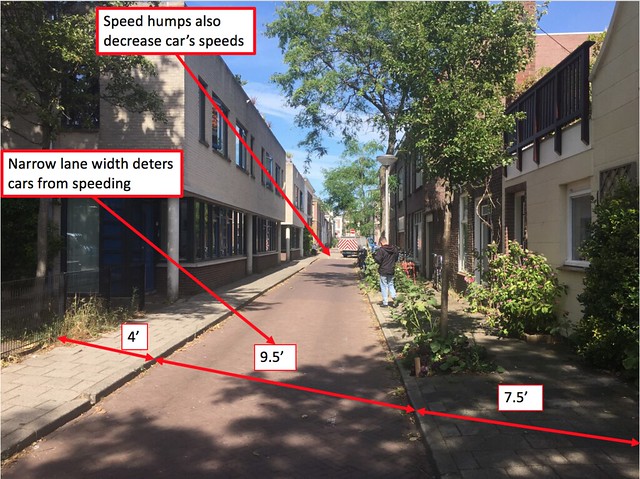

Narrow roads and frequent speed humps simulate a feeling of confinement, resulting in more cautious drivers and lower driving speeds. In addition to the physical barriers, most of the pavement in the woonverven was stamped red asphalt, indicating a shared space/zone to drivers which ensured drivers would travel slowly through the neighborhood.

Figure 8: Cross section of a street in Westerstraat. The narrow lanes and speed humps in the picture deter cars from traveling too quickly.

Video: A car and a pedestrian meeting in Westerstraat. Because the car is traveling so slowly, the driver is able to see the pedestrian, and the pedestrian comfortably walks past the car. These types of conflicts in woonerven do not create dangers for vulnerable road users such as cyclists and pedestrians since the car travels so slowly around the chicanes and speed humps.

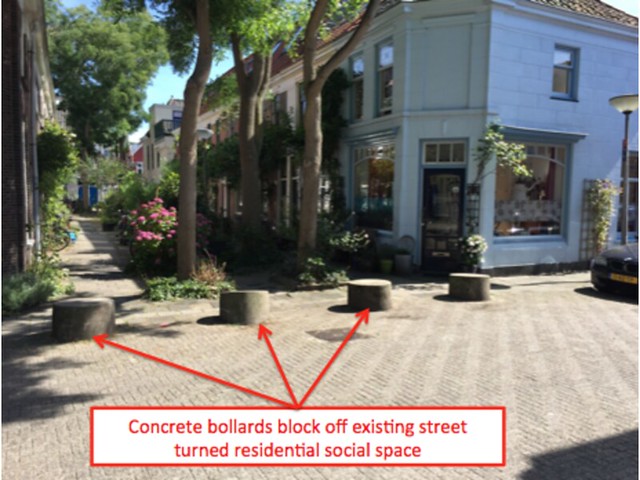

In addition to cars traveling slowly due to the chicanes, speed humps, and narrow lanes, cars will not be able to cut through the neighborhood because pedestrian only zones were created by blocking off streets with bollards. By blocking off these areas, the planners created a more beautiful space for people to live and interact with their neighbors.

Figure 9: Bollards in Westerstraat preventing cars from entering the pedestrian space

Street Furniture

As a result of these system safety traffic features and the reduction of motor vehicle traffic volumes and speeds, the neighborhood streets became extensions of the homes for the residents. Residents began to beautify their new living space with box planters, wall murals and paintings, benches, and playgrounds. This new available space became a community “hang out” for children to play and neighbors to socialize in the street as opposed to a means of just entering and exiting their homes.

Figure 10: Planters and murals in Westerstraat. The decoration people put on their houses creates a beautiful neighborhood for all residents to enjoy

Figure 11: Decorations for a festival residents put up in Tanthof. Because the banners span multiple houses, there is a community feel to the decoration.

Although we would have liked to capture children of the neighborhood utilizing the woonerven as they were intended, we found that most of the children in travelled to a local playground instead of playing in the street.

Figure 12: Children playing in a playground in Westerstraat.

Implementation in the US

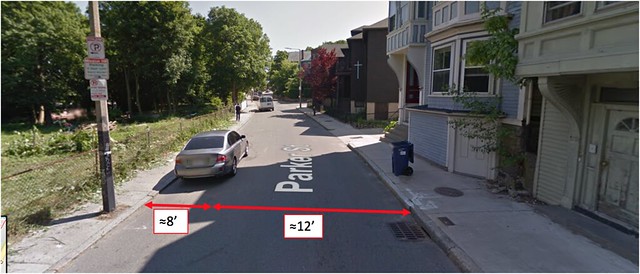

One place where woonerven can be implemented in the US is Mission Hill in Boston, MA due to the high speeds drivers travel through the neighborhood. Mission Hill is primarily residential; therefore, drivers should not drive through unless their destination lies within the neighborhood. For example, Parker Street is a one-way street that is at times over 20 feet wide. Allocating approximately 8 feet for parking, cars have at least a 12 foot travel lane, making speeding comfortable (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Cross section of Parker Street. It is a relatively wide street for one-way car travel.

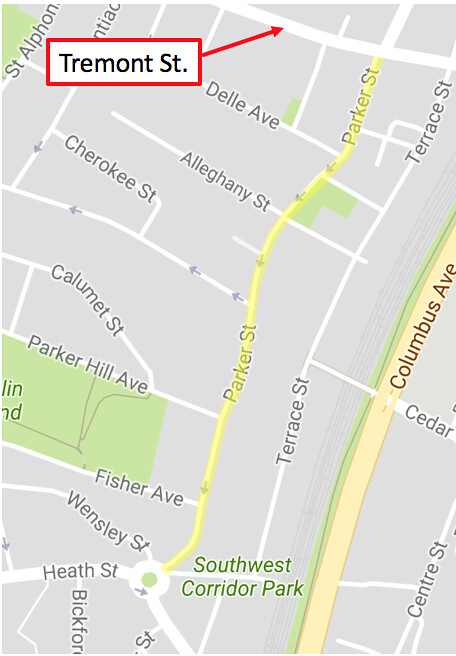

Parker Street can also be used as a cut-through between Tremont Street and Heath Street, two main roads in Boston (Figure 14). Since there are no deterrents to fast speeds, drivers frequently use this cut through from Tremont Street to Heath Street.

Figure 14: Map of Parker Street. Although it is a one-way street, Parker Street can be used to travel from Tremont Street to Heath Street even though Parker Street is not a distributer road.

Using some of the principles in Dutch woonerven, Parker Street could be improved by simple measures such as alternating parking on either side of the street. By designating where people can park by adding a “P” in the parking space, artificial chicanes are created, causing cars to slow down as they meander through the street. Speed humps and raised crossings can also be added to slow cars down. If the street is redesigned so that few people want to use the street as a cut through from Tremont Street to Heath Street, traffic would greatly decrease and cyclists and people could enjoy the street more.