When I started this blog, I felt pretty comfortable in my conviction that perpetual motion machines were unpatentable. After all, the law is clear that an invention must be useful before it can be patented, and impossible things are not useful things.

As we have gone on this journey together, you and I, I felt I could show you the wonders and misdeeds of the human mind, safely assured that we lived in a rational universe that followed predictable rules. As a patent attorney, I am bound by two different sets of laws–the human and the physical–and I foolishly expected others to feel the same. I should have known better, and I am sorry.

Today I decided to do a search for patents that the USPTO classifies as perpetua mobilia–perpetual motion machines. Whenever a patent application is filed, some clerk classifies it according to the technologies that it represents. The classification system is extremely fine-grained, and is honestly a pretty fascinating exercise in the taxonomy of human knowledge, assuming you are a big fucking nerd like me.

Here is one example, searching the class of perpetua mobilia that allege perpetual motion of a fluid in a closed loop. You will see that, as of the time of publication, there are 73 matches. That is, seventy-three different patent applications have been filed, which the USPTO initially believed to include this specific type of physically impossible perpetual motion machine, and which have issued as patents.

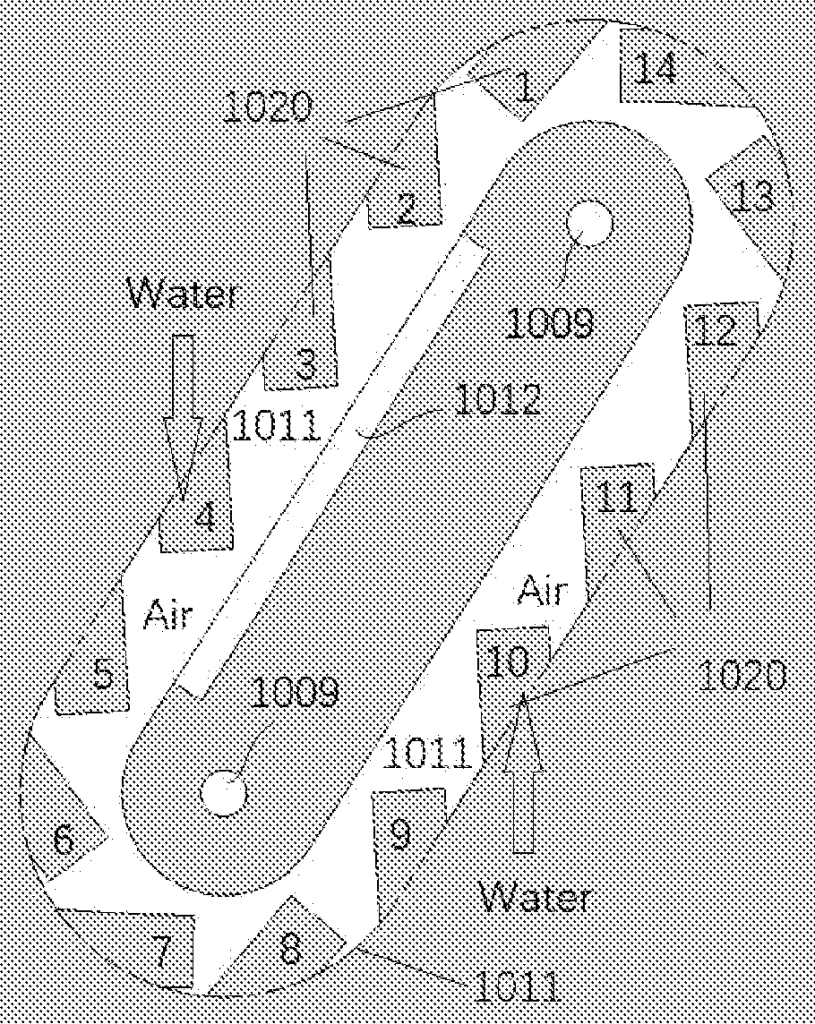

Here is one of them. The gravitational turbine engine:

As best I understand it, the idea is that the weight of gravity pulls down the water on the top, and “buoyancy” pushes the upward from the bottom, resulting in rotation of the device, which can be used to generate electricity.

What is more difficult to understand is why the “buoyancy” on the bottom would not apply to the water on top, nor why gravity would not apply to the water on the bottom. The patent claims some sort of “shielding device.”

I know fluid mechanics is tricky, but the whole point of buoyancy is that it represents the imbalance between the density of water and the density of an object floating in the water. Gravity is the only reason buoyancy works at all, as it pulls the heavier water down below the lighter floating object. It seems that the gravity and the buoyancy would be roughly constant around the entire loop.

I was happy to see that the patent examiner agreed with me, at least at first:

The work performed by and against gravity has to add up to zero around the loop. The system utilizes gravity to sink down objects until they come to the section of the loop effected by the ‘shielding device”. This device, without clear explanation, causes the object to pick up energy. This added energy causes the object to round the bottom of the loop and by buoyancy travel to the top of the loop. Finally, extra work is needed to cause the object to round the top of the loop and begin its gravity descent.

Even allowing for zero viscosity and friction the amount of work required for the loop to make one revolution has to be zero.

The Examiner has not found any motive force in the disclosure that starts and keeps moving the system.

Office Action dated October 2, 2022, in file wrapper for USP 11,047,359

So how did we get from that rejection to a patent? Well, the applicant filed four heaps of nonsense. I will include them below for your review, because I’ll be damned if I’m going to try to read and summarize them. The one alleging “technical prejudice” is pretty tempting, though.

I doubt that these arguments won the day. Instead, a new set of claims was filed and the inventor had a telephone conference with the Examiner. I don’t know what was actually said during the interview, but the interview summary states, “Claims look good which is the most important.” The Examiner’s statement for allowance then appears to take the inventor’s assertions at face value, despite the clear impossibility of the device’s function.

So the examiner basically shrugged and allowed the claims, confident that the quality assurance team wouldn’t bounce the claims for being too broad. A useless patent was issued, the examiner got his points, the “inventor” was happy, and that was the end of it.

During law school, when learning about the “utility” requirement for patentability, we discussed whether the requirement was really necessary. Assuming it’s even possible to infringe an impossible patent’s claims, why would anyone bother? One could argue that such patents are ultimately harmless. On the other hand, it is easy to imagine such a patent being used as a perpetual fundraising machine, with the imprimatur of the USPTO lending credibility to the scam.

For me though, I just find them kind of yucky.

Anyway, here are the responses filed by the applicant, in case you have an abundance of time and patience. It’s only 85 pages, with lots of pictures:

The 85 pages are great! There’s a section describing the 2nd law of thermodynamics as a technical prejudice.

LikeLike