Celebrating LGBTQIA+ Artists in the Collection: Charles Demuth (1883-1935)

In honor of LGBTQIA+ Pride Month in June and our upcoming Virtual Pride Celebration Week, July 27-31, we are highlighting LGBTQIA+ artists from our permanent collection.

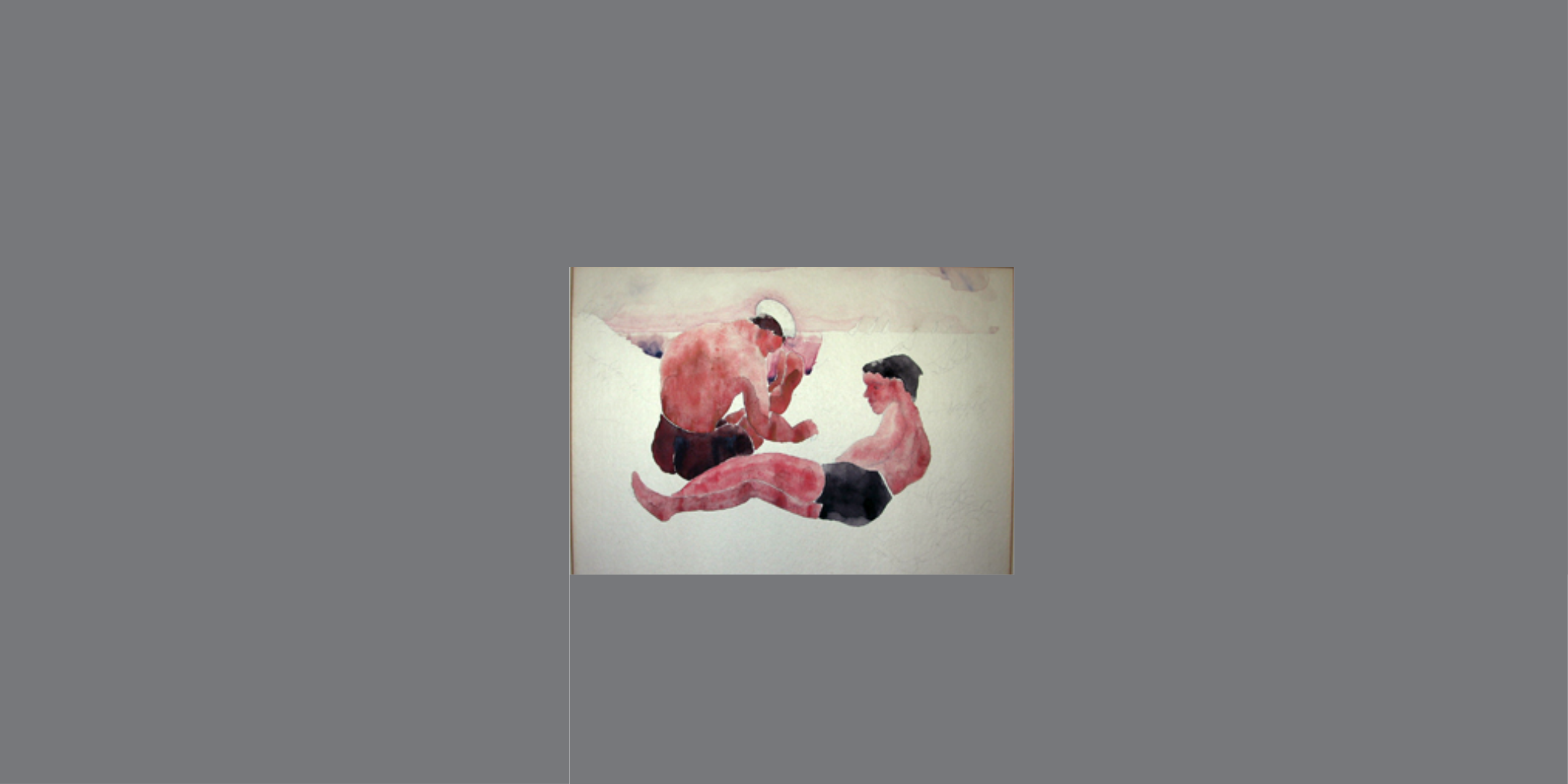

The third LGBTQIA+ artist from that we are celebrating is American modernist Charles Demuth, whose watercolor Beach Study, Number 2, is part of the Museum’s permanent collection. Demuth was one of the first artists to embrace Modernism and give it a uniquely American point of view (3). He became known for two signature styles, delicately tinted watercolors of flowers, fruits and figures, and precisionist, cubist-derived architectural landscapes and cityscapes. He also depicted early 20th century American gay subculture in evocative, private watercolor paintings.

Born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Demuth’s love of art began at a young age in part due to an unfortunate accident. When he was 4 years old, he injured his hip and was bedridden for a few weeks. To keep him occupied, his mother gave him crayons and watercolors, and his love of art began. Unfortunately, this injury caused him to walk with a noticeable limp and necessitated the use of a cane. Due to his physical frailty, he experienced an isolated childhood and throughout his life had the sense of being an outsider. After his hip injury started to heal, he began private art lessons in still life and landscape painting with Martha Bowman. (3)

Demuth studied at Franklin and Marshall College, graduating in 1901, and first studied art at the Drexel Institute and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia until 1911. While at the Academy, living in a boarding house, he became friends with William Carlos Williams, who was an American poet associated with modernism and imagism. In 1907, Demuth exhibited his work for the first time in the 8th Annual Exhibition of the Fellowship of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Demuth also traveled to and studied in Paris from 1907 – 1908 and again from 1912-1914, where he met and became friends with fellow American artist Marsden Hartley.

After leaving school in 1911, he returned to Lancaster where he began to paint simple floral watercolors, inspired by the flowers in his mother’s garden. Demuth also traveled frequently to New York City over the years, where he developed friendships with Alfred Stieglitz, Marcel Duchamp and Edward Fisk, and to Provincetown, Cape Cod, MA for summer vacations, which is most likely the location of the Museum’s work by Demuth. He became a member of Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 stable of artists that included Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, and John Marin, among others. In New York, he frequented the city’s nightclubs and Harlem jazz clubs, enjoying the creative, bohemian atmosphere of the Harlem Renaissance. During this decade, Demuth also created a series of figurative works based on vaudeville performances he saw in Lancaster and a series of “literary illustrations” for contemporary works by Henry James and Émile Zola.

In 1917, Demuth traveled to Bermuda, joining Marsden Hartley, and began experimenting with Cubist and modernist principles in a series of architectural and landscape paintings that would come to be known as Precisionism. These works were exhibited later in the fall of that year, in an acclaimed two-person exhibition at the Daniel Gallery in New York with modernist painter Edward Fisk.

During the late 1910s and early 1920s, Demuth traveled to Paris where he was part of the avant-garde art scene. The Parisian community was much more accepting of Demuth’s homosexuality, and a number of his paintings, like Turkish Bath with Self Portrait, which were not intended for public view, depict the sexual subculture of postwar Paris and the evolving gay subculture in New York. These works have historical significance because they capture an emerging culture that was very different from the mainstream at that time. (2)

Demuth suffered from an illness that forced his return to Lancaster in 1921 where he was diagnosed with diabetes and began experimental treatments. Two years later, Demuth started painting his series of “poster portraits,” which were symbolic tributes to modern American artists, writers, and performers, including O’Keeffe, Marin and Dove. One of the most well-known of these poster portraits is his tribute to the poet William Carlos Williams: I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928), which is considered a pre-cursor to Pop Art and one of his most famous Precisionist works. During the same year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased one of his works, and he had successful solo exhibitions in the following years.

During the 1920s, Demuth began exploring the face of industrial America, which would become a major theme in his artistic output that included Machinery (1920), which illustrated industrial architecture in Lancaster, and Incense of a New Church (1921), a Precisionist painting depicting billowing industrial smoke through geometric curved forms in the foreground of a crisp city skyline.

In 1927, the first book on his work was published, and that same year, he began a final major series of seven paintings based on the architecture of Lancaster, including the well-known My Egypt (1927), which depicts a massive grain elevator taking up the majority of the composition, with intersecting beams of light. Critics have suggested that Demuth’s title, My Egypt, and the size of the grain elevator in the composition is both celebrating American industrialization yet critiquing the negative effect of industry on American workers. These works would become iconic representations of the industrialization of and its effects on small-town America. Just 8 years later, Demuth died in Lancaster at age 51 from complications of diabetes.

Demuth was a skillfully versatile artist, creating delicate watercolors of fruit, flowers, and figures, and modern industrial landscapes that emphasized sharp lines and clear geometric shapes. A proponent of the Precisionist movement, Demuth’s work was crucial to the development of modern art in this country in the 20th century. Over the course of his artistic career, he painted with watercolor, oil and tempura, completing about 750 paintings and 350 drawings, received favorable reviews, and sold numerous works. The Demuth Museum in Lancaster, dedicated to developing awareness, understanding and appreciation of the artwork and legacy of Charles Demuth, contains 40 works that span the artist’s career, and an extensive archive and library.

As a tribute to LGBTQIA+ PRIDE month in June and our upcoming Virtual Pride Celebration Week, July 27-31, we are showcasing artworks by LGBTQIA+ artists in the Robertshaw Gallery windows. Due to the fragility of Demuth’s watercolor on paper, Beach Study, Number 2, we are unable to display it in the Robertshaw Gallery windows. Lawrence Calcagno’s Black June (1954), and Paul Warhola’s Paul and Andy (1990), are currently on display in the windows and can be viewed from outside on the Swank Terrace!