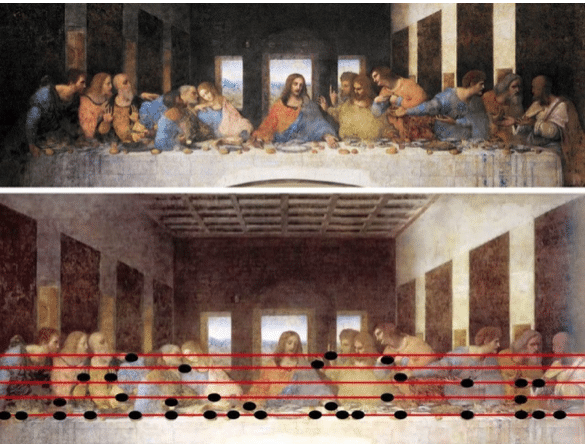

There’s a musical soundtrack embedded in Leonardo da Vinci’s famous Last Supper. That’s what an Italian musician and computer technician has claimed to have discovered, and considering how the hidden melody sounds when played on a pipe organ, it seems pretty unlikely to be a coincidence.

Giovanni Maria Pala thought that the loaves of bread as well as the positions of the hands in Leonardo’s painting suggested musical notes. He laid a musical staff over top on his computer, but when played, the tune was nonsensical and unappealing. It was not until he played the notes backwards, from right to left, that he found the melody he was looking for. Backwards writing was a peculiarity of Leonardo’s; he famously wrote his notebooks backwards, which scholars presumed kept prying eyes from uncovering his secrets.

As you can hear in this Youtube link, the music is slow and dirge-like. It suggests a musical score belonging to a mystical Requiem, a somber soundtrack for the moment when the disciples learn that one of them would betray Christ.

The theory was deemed “plausible” by Alessandro Vezzosi, a Leonardo expert and director of the artist’s museum in Vinici. Vezzosi had previously suggested that the placement of the hands might relate to Gregorian Chant.

“There’s always a risk of seeing something that is not there, but it’s certain that the spaces (in the painting) are divided harmonically,” Vezzosi has said. “Where you have harmonic proportions, you can find music.”

The Hidden Self-Portrait Challenge

Clara Peeters, Still Life with Cheeses and Pretzels, oil, 34.5 cm × 49.5 cm (13.6 in × 19.5 in)

Plenty of paintings, famous and otherwise, contain secret or subliminal messages, and subtle (and not so subtle) unauthorized portraits of the artist. For example, there’s a tiny self-portrait hidden in Clara Peeters’ 1615 still life (above). Can you spot it? (The answer is at the bottom of this page.)

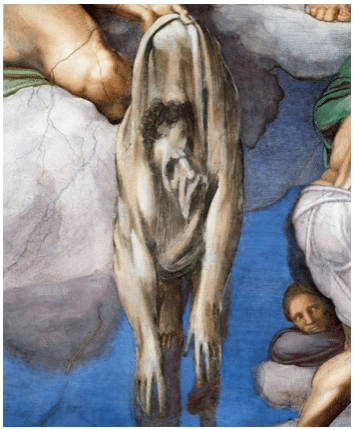

Michelangelo famously incorporated a depiction of himself as a tortured figure in the Sistine Chapel frescoes. Here he casts himself as the skin of the flayed saint, the martyr Saint Bartholomew.

This one’s so weird and complicated, it’ll have to be the subject of a whole future Inside Art of its own.

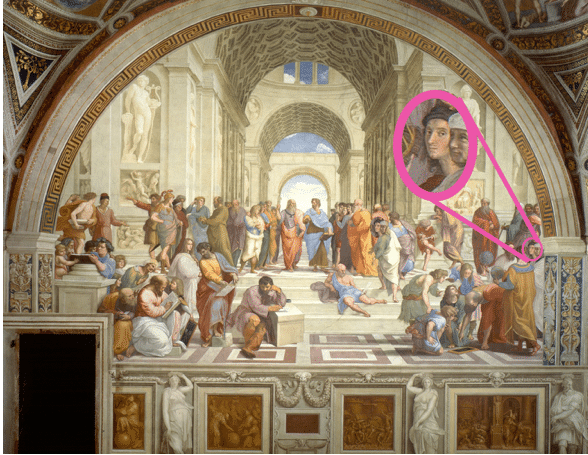

For a not-so-hidden self-portrait, look no further than Raphael’s “check me out!” inclusion of himself in his incredible Renaissance masterpiece, The School of Athens.

This painting casts contemporary figures in the roles of famed philosophers, mathematicians, scientists, and astronomers of classical antiquity. Therefore, it includes portraits of Leonardo and Michelangelo. The “divine Raphael” felt justified including himself among the august company and rightly so.

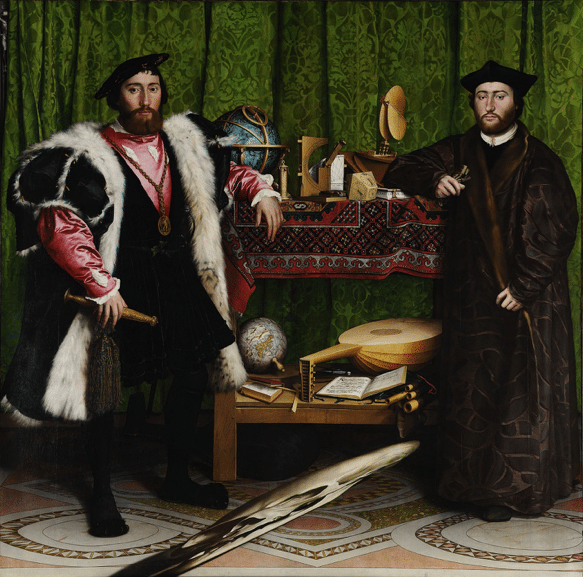

Turning to yet another Renaissance painting, there’s an amazing “Easter egg” (i.e., insider visual jokes and other random things placed where they’ll eventually be found, especially in software, video games, and movies) in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (below). This painting is so full of variety and finely rendered detail that it takes a while to notice the weird gray shape wedged sideways in the foreground.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 81 in × 82.5 in.

This shape is actually an “anamorphic,” an technique invented during the Renaissance. Seen obliquely, from the side, the shape resolves into a giant 3-D skull, as demonstrated in the photo below:

Precisely why Holbein embedded such a visual puzzle is lost to history. One theory is that the painting was meant to hang beside a doorway or in a stairwell, so that persons entering the room or walking up the stairs and passing the painting on their left would be confronted by the unexpected emergence of the optical illusion. Neat theory, but it still doesn’t explain why he put the skull there to begin with.

Very likely it has something to do with the memento mori tradition: artists working in this genre embedded a reminder that the viewer would one day be no more (memento mori = “remember you die”) so they’d better live a good and Godly life if they knew what’s good for ‘em.

And here’s the answer from the challenge above. Clara Peeters’ already small (9” x 13”) 1615 still life contains, in minuscule detail, a teeny tiny self-portrait in the reflection on the metal cap of the clay jug in her Still Life with Cheeses and Pretzels.

Clara Peeters, detail from Still Life with Cheeses and Pretzels., 9” x 13” oil.

Self-portraits are an important part of the history of painting If you’d like to perfect a technique for painting your own, you might want to look into Gregory Mortenson’s Realistic Self-Portraits teaching video.