Maurits Cornelis Escher, better known as M.C. Escher, forged his artwork out of a pure mathematical philosophy.

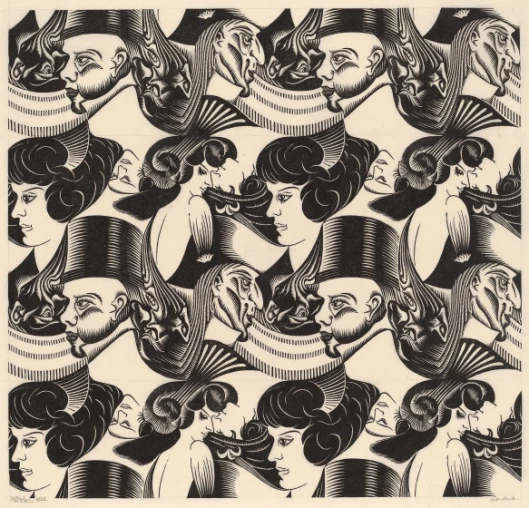

In an age untouched by computers, M.C. Escher crafted unique pieces that highlighted the vulnerability of human perception to illusion. Raised to be an architect, Escher’s brand of imagery speaks to his viewers as one that flawlessly integrates the disciplines of mathematics and visual art, and thus stands out a myriad of communities: in the popular media, where his illusions are eye-catching; in the mathematical community, where his work on tessellations, Droste effect, topological spaces, polyhedra, and hyperbolical geometry prior to a computer-aided era continue to fascinate; and the art community, who often regard him as the father of a movement and as an idiosyncratic artist prioritizing a technical, mathematical approach over a intuitive, humanistic one that seemed to wholly incongruous with the era of art that he was born in.

A fascinating window into M.C. Escher’s worldview can be found in his essay on tessellations in 1957. Tessellations are a highly technical mathematical concept, often considered only in the abstract; Escher’s essay on the topic reflects his rigorous upbringing. A quote from this essay, in particular, comes to mind:

“In mathematical [communities], the regular division of the plane has been considered theoretically… Does this mean that it is an exclusively mathematical question? In my opinion, it does not. [Mathematicians] have opened the gate leading to an extensive domain, but they have not entered this domain themselves. By their very nature they are more interested in the way in which the gate is opened than in the garden lying behind it.”

M.C. Escher in this single quote reveals to the reader his motivations behind leaving his mathematical career and applying his abstract knowledge to the field of the arts. His interdisciplinary perspective is highly evident in this quote, but it also demonstrates his disliking of abstraction in mathematical philosophy when he notes his disappointment in the mathematical community for not actualizing the potential behind tessellations.

M.C. Escher is well-regarded as an innovator in the manipulation of vanishing points to create the warped Droste effects we see in works such as Print Gallery and Relativity as well as the spherical reflections in Hand with Reflecting Sphere. However, I find particularly fascinating the mathematical technicalities known as tessellations that Escher utilized to produce works such as Circle Limit 3, often praised as mathematically consistent with space as understood by modern cosmology by reflecting the expansion of the universe. A tessellation is known as a geometric pattern which stretches without limit (theoretically) across a plane without exception such that the sum of the interior angles in each vertex must equal 360 degrees. The only possible methods of forming tessellations in 2D are by using triangles, squares, and hexagons. We see from Escher’s work that the tiles that he forms are primarily of hexagons, and that the tiles when considered one by one show repeating patterns that have been rotated as to fit into each other and completely occupy the space provided without any gaps.

It is interesting too that his work only came into the public consciousness when he was 70 years of age, reflecting the cruel likelihood of obscurity for many artists and innovators.

“As far as I know, there is no proof whatever of the existence of an objective reality apart from our senses, and I do not see why we should accept the outside world as such solely by virtue of our senses.”

– M. C. Escher