Chris Drury (born 1948, Sri Lanka) as been described as a Land Artist but he himself says that he seeks to make connections between: Nature and Culture; Inner and Outer; Microcosm and Macrocosm .

To this end he collaborates with scientists and technicians from a broad spectrum of disciplines and technology and uses whatever visual means and materials that best suit the situation.

His has made works outside all over Europe and America, and recent projects involve a British Antarctic Survey residency in Antarctica in 2007, a solo exhibition Mushroom|Clouds at the Nevada Museum of Art in 2008 and A work for the Australian National University in Canberra – The Way of Earth, Trees and Water. This year he has made a work outside for Chaumont Sur Loire in France – Carbon Pool and an exhibition with installation at Oppland Art Centre in Lillehammer, Norway. His work Carbon Sink in Wyoming sparked a worldwide furore in 2011 about the burning of fossil fuels in connections with dying forests in the Rockies. He is currently working with three organic farms in Dorset, England for Cape Farewell on sustainability and climate change.

Mothership: Your work strikes me as the most religious work I’ve seen, outside of certain water-sculpted stones or configurations of vines, or in indigenous or Japanese work of past centuries that understands space and listening. “Religion” is a much-abused, and therefore misunderstood and maligned term these days, so to be clear, what I mean here is found in the roots of the word, the Latin “ligare” that, as seen in “ligature” and “ligament,” means “binding.” And so “religion” here is meant in that way, as a “binding back to” or reconnecting to something beyond ourselves (that is ourselves), in the sense that we are made of the same stuff as stars.

You do this work of binding back, of showing the connections between the vast and small scales that we humans live between. In your notes for your recent Cradle of Humankind project at Nirox, South Africa, where a 10 km meteor struck the earth 2 billion years ago, you asked yourself, “How do you stretch your mind to include such a massive event that happened in such an unimaginably distant time?” And this is some of what you do, give glimpses of geologic time in arctic ice cores or in desert bacteria that gave rise to complex life forms—you make these things that are beyond us, beyond our scope of sensing, somehow intimate and of us. In other works, you simply make visible the essential beauty of a place, a glacier, a canyon, a headland, a scrap of forest or field. This is the kind of longer yet closer view that we need now, as the blinkered vision of short-term gains destroys the dazzling weave of life on earth.

Sometimes you do this work through old ways of seeing, through working with materials by hand. You then sometimes join this handmade techne with new ways of seeing through high-tech tools. How are ideas from science refining or stimulating your understanding and your vision? (I recall Martin Kemp speaking of your interest in flow patterns and chaos and complexity…)

Chris: My first interest in science came from theoretical physics – particle physics, quantum mechanics, chaos and complexity theory, mostly through reading. Science was making Zen-like statements, such as a wave being either a movement or a particle, depending how you look at it at any given moment (the viewer being part of the equation, which was something I had intuited for a long time) – or proposing that effect can come before cause, challenging the meaning of linear time. Also chaos and complexity theory posed such extraordinary ideas. It was complexity theory that lead me towards flow patterns in the heart and eventually became the underlying factor in so many works, particularly Heart of Reeds. The idea is that as things become more complex, instead of descending into chaos, they start to form coherent patterns, which is how we get such incredible biodiversity within natural systems on the planet, in a dynamic shifting balance. When you look at a turbulent mountain stream, what you see in the water seems to be a chaotic pattern, but is in fact a number of very coherent forms working together, all built around vortices which turn out to be a pure manifestation of an underlying energy or force in the Universe. It is there in the microcosm, sub-atomically, and then in blood flow, in rivers, but also in the macrocosm, in weather systems and the formation of galaxies. Theodore Schwenk, in his elegant book Sensitive Chaos, saw it all before chaos theory.

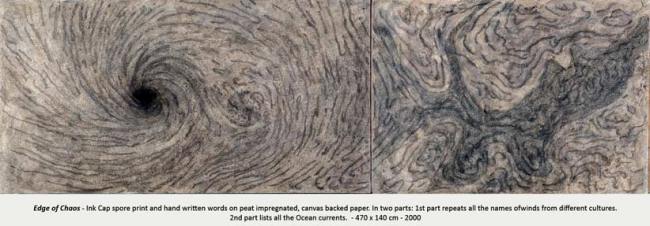

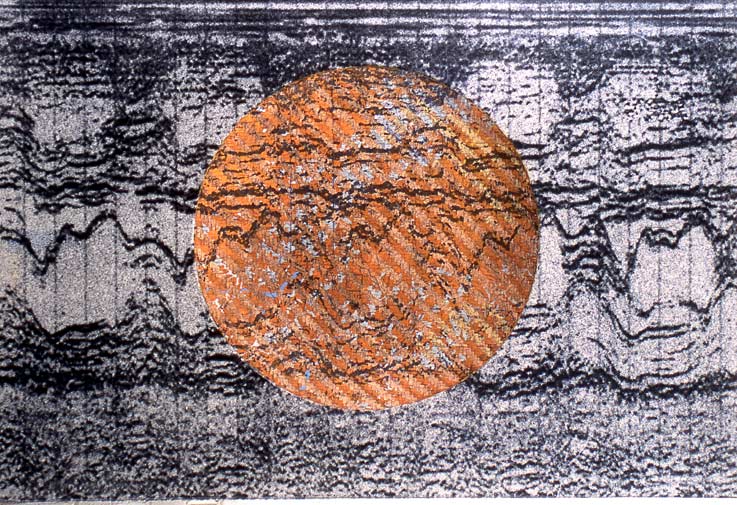

Out of this thinking a seminal work of mine emerged in 1999 through a flash of insight. This was the large work on paper, Edge of Chaos, and was a way of looking at climate as a coherent pattern, based around the relationship between ocean currents and wind, giving us our dynamic local climates. This work takes two complex patterns: one based on the double vortex pattern from the cross-section of tissue at the apex of the heart (illustrated by Theodore Schwenk after Benninghoff), what is now referred to in medicine as a Cardiac Twist; and the other a complex pattern of wood grain in a redwood trunk found washed up on the beach of the Lost Coast of California.

The work is in two parts made up of densely hand-written words in ink which overlay a painted wash of these two flow patterns. The one on the left, on the heart pattern, lists and repeats all the names of winds from different cultures in the world from zephyrs to hurricanes. On the other redwood pattern is repeated all the names of ocean currents. This is an illustration of complexity but it also makes links to culture. Wind can actually shape the psyche of nations; think of the Foen and the Mistral in the Mediterranean, the typhoons of Asia, the hurricanes in the West Indies and the monsoons of India and the Himalayas. I think what you and Mahoney call rta [MS: occurring later in the interview] is embedded in Edge of Chaos.

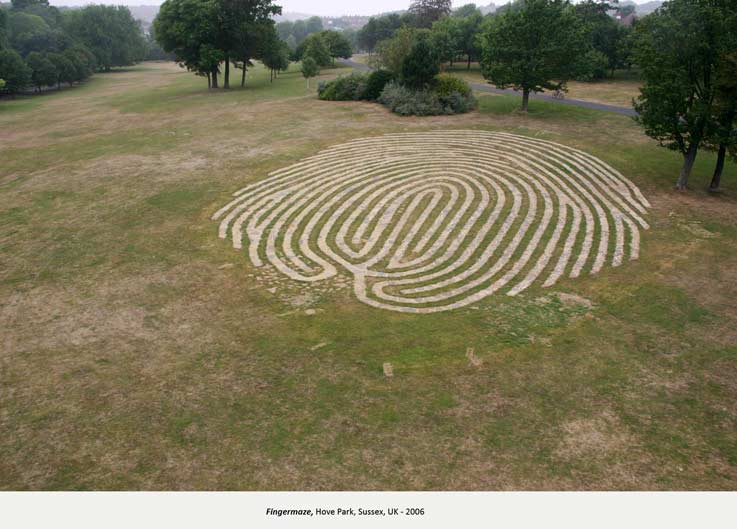

It was this work which drew me towards working with heart surgeons and radiographers looking at similar systems within our own bodies and comparing these to systems on the planet. The work which emerged from these collaborations and residencies within hospitals lead to the biodiversity work Heart of Reeds, all the vortex and whirlpool works: Carbon Sink, Echoes of the Heart, Rivers of Stone, Fingermaze and Redwood Vortex. It also led me to working with astronomers at Vanderbilt in Nashville where we made Star Chamber, and to Antarctica working with glaciologists looking at the flow patterns of 4 kilometer-deep glaciers.

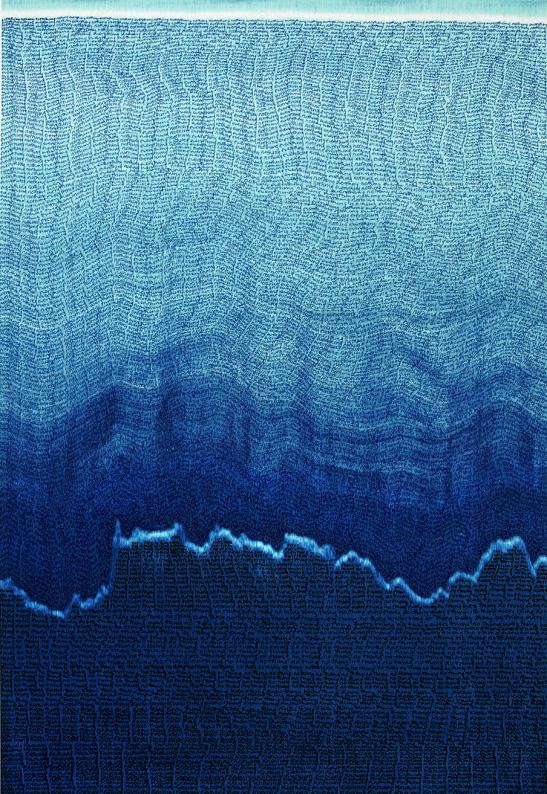

In a small tent close to the Ellsworth Mountains, deep in the interior and a short flight to the pole, Hugh Corr, a scientist working on echograms of this particular glacier, got out a laptop and showed me some radar images of the cross-sections of ice beneath our feet. “You may be interested in blood flow in the heart,” he said, “ but these echograms show the heartbeat of the earth.” This poetic statement came from one of the most pragmatic men I know. It was he who saw the connections to what I was doing and realized there was ground for cross-fertilization – a way, perhaps, of bringing the observer into the observed.

(See more about this echogram of the Antarctic print in Works for Sale

http://chrisdrury.co.uk/everythingnothing-iii/)

Mothership: This “bringing the observer into the observed” brings me to how your work is often a kind of reworking of the old sacred geography, attentive, reverent ways of relating to a region that that became a region’s official religion, until nationalism took over. These older traditions of sacred place often involved myths of deities’ bodies fallen to earth, or they mapped a divine human figure to the land. Yours is a global and contemporary sacred geography in which you reconnect our (increasingly disembodied) human bodies to the earth. Such as in this mapping of the glaciologist’s heart with the pulse of the earth’s plates shifting below the Arctic. Can you say more about your work with doctors/hospitals? With maps and mapping the body to the land?

Chris: I moved towards Medicine because through Schwenk I found that blood moved in the heart the same way water and weather moves on the planet, and just when I discovered that, somebody asked me if I would like to do a residency in a hospital in Hastings, Sussex. Just down the road. I jumped at it and asked to work within a cardiac ward and have access to all sorts of body imaging data. At the same time I was introduced to Frances Wells, a heart surgeon at Papworth in Cambridge, who invited me to come up and witness an open heart operation. It was Francis Wells who later used my blood drawing, Heart River, to illustrate to students what a Cardiac Twist is. A year or so after this I made two installation flow works (Rivers of Stone and Fingerprint) in adjoining courtyards at Russell’s Hall Hospital in the Midlands. Here I was able to start making concrete all the research into blood flow of the previous years. Finally, I was invited by the heart surgeon Mark Dancy to make a blood flow courtyard (Echoes of the Heart) at Central Middlesex Hospital, adjoining his Cardiac ward. It was Mark’s department which agreed to do an echocardiogram on the pilot who flew those echogram flights in Antarctica and so enabled me to make the work Double Echo, a print of which hangs on the walls of that particular ward.

MS: You’ve mentioned the stale air of the art world, (“like a steamed up car”—ha), what I think of as ingrown vision. And so in your art you often turn towards a wider-minded participation with the world, not only with these scientists and physicians, but also with communities who are stewarding the land where they live. It seems that collaboration always opens up and refreshes how and how much we can see…

Chris: I know a few artists who collaborate with a particular scientist and they may start from the same point exploring together one particular aspect to see what arises for them both; I am quite envious of this because it is pure collaboration. However, in my experience in talking with scientists from many disciplines they all complain that their process is one of continual data collection and experimentation, the empirical method where there is no space to play and wonder – and they often envy the artist’s freedom. Also their area is often so specialized that there is no space and time to see how one area might connect with another, how particle physics might have a bearing on ecology or meteorology, for example. But as an artist I can look at the bigger picture and act as a linking conduit between many disciplines.

Science may be one, but then local indigenous knowledge is often just as significant. What the farmer knows from continual exposure to the processes of the natural world can be every bit as revealing as the latest findings from CERN. The farmer, however, may not know about the similar findings of the ecologist and vice versa. So I have often seen what I do as a way of making connections through the dance of mind and body with material substance.

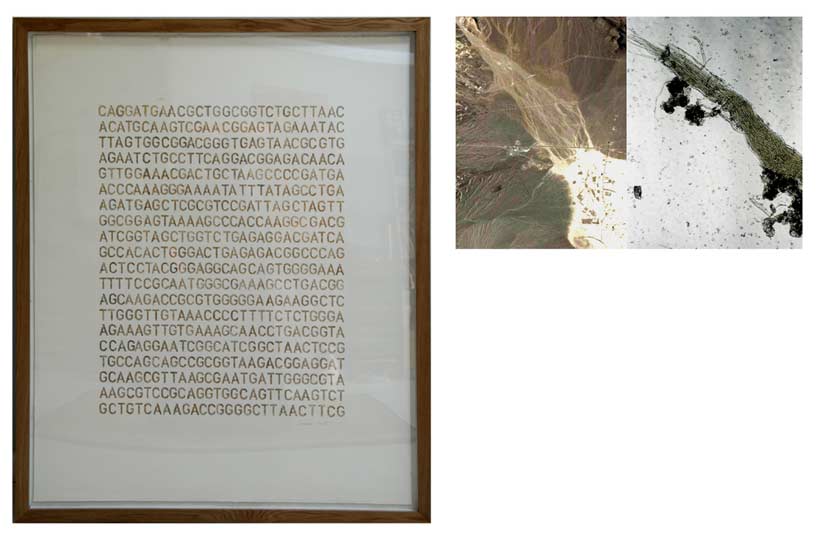

One of the most interesting interactions with a scientist was with Dr. Lynne Fenstermaker at the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Nevada. While I was at the Ellsworth Mountains in Antarctica, one of the scientists there mentioned that they had discovered a very primitive bacterial life form in the rocks of these lifeless mountains. In effect, this bacteria was waiting for a time of warming when it could start the process of breaking down rock into mineral earth on which new life could grow. The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) provided me with the gene sequence for this proto-bacteria and I made the first work in the series Life in the Field of Death by stenciling this gene sequence in Antarctic earth.

By coincidence the BAS had all their Antarctic ice cores analysed by the DRI in Nevada, so when I was at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno working on the show “Mushrooms Clouds”, I was very anxious to see something of the Nuclear TestSite on which the DRI carries out a lot of research, mostly because it is an untouched pristine desert with no cattle ranches. So before I went down to talk to the scientists working there I sent down a list of questions in advance, one of which was ‘what is growing in the soils of ground zero where over 100 bombs were detonated above ground?’

Lynne, who is a soil biologist, saw that I was interested in micro/macro and she remembered that they had a microscope image of Microcoleus vaginata, taken out of those very soils. She then looked up a Google Earth image of the Test Site from space and saw that the two images were very similar, as the Test Site is in a dried-out river wash which mimics the linear strands of the sino-bacteria. It was these two images which she brought to our lunch meeting and which we later used in the show. This formed the basis of the second in the Life in the Field of Death series, for which we stenciled the gene sequence of this life form onto the walls of the museum in Test Site Earth.

Perhaps more interesting, however, was the fact that this minute, strand-like life-form which you can find in many soils is the first plant that learned to turn CO2 into oxygen and so paved the way to life on the planet. We owe our very existence to it, and it is no small wonder that it survived nuclear explosions. Last year in Western Australia, close to the shore, I saw a collection of thrombolites, a very ancient plant and a close relative of Microcoleus, and the previous year in South Africa, on the Cradle of Humankind I had seen fossilized sino-bacterial plants called stromatolites – all the ancient life forms giving rise to the amazing biodiversity we have today.

MS: Again and again in looking at your work, I keep thinking, ‘these are old things; these are true things.’ In an artist’s statement you made some years ago, you say, “What is known is always from the past./Through knowledge the new is a reworking of the old.”Can you say more about this sense of oldness and/or reworking oldness in your work?

Chris: Something that is ancient often has a new equivalent, because in the Universe everything obeys the same laws, it is just that we don’t often see this, so in a way my art acts like a conduit and gently reminds people of these ancient principles. However, anything that is totally new is always revealed in present intuitive time and never through thought or knowledge, although we may later use thought and knowledge to give the new a tangible form. Culture is part of this process, such as when you think about the relationship say of wind, ocean currents and human culture, or the fact that mushrooms are plants which can feed you, kill you, cure you or even make you see visions and as such they are also a human metaphor for life, death and regeneration.

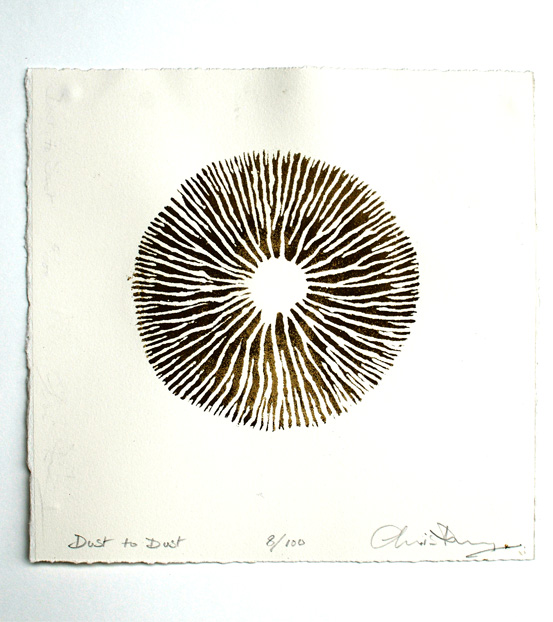

MS: Mushrooms are a recurring image in your work over the years. You speak of mushrooms as killing and curing; this notion of poison as medicine is an element a Buddhist worldview arising from older, underlying ideas. This mushroom image you work with often includes words, spiraling in finely scripted, incantatory rings, matching the mushroom’s delicate fretwork. This killer-curer is a potent image for our time, with the poisons humans are unleashing on global scale. Was the hub of Medicine Wheel your first mushroom image, and how did you arrive at the idea? Have you ever spent time with Cage’s Mushroom Book; it would have been fun to see a collaboration between you two on this!

Chris: Yes, it was, and Medicine Wheel was a key turning point in my work at that early stage. And, yes, there is a link to John Cage, because I read of his interest in fungi while I was a student in London, and I used to go up to Epping Forest and search for both edible and poisonous varieties in the Autumn, often along with the Italian restaurant owners. Cage is someone who I have consistently admired.

MS: You’ve said that Medicine Wheel, that work of daily attention to the ground, was the seedbed of the work you’ve done these past 30 years. Medicine in most cultures is understood as a re-balancing of what has gone out of balance. Your work, as noted earlier, has this sense of restoring us to right relationship and to a deeper attention that is healing. This aspect of your work is seen in Destroying Angel, an installation in Nevada, near the nuclear testing sites, of a mushroom-cloud shape made of sage leaves and sage burning on video nearby—an old local purification ritual set in a contemporary exalted space of the art gallery. In this way, though words are confining here, your works could be called spiritual and political, an integral aesthetics, a way of seeing.

Medicine Wheel was literally a weave of your days. In terms of craft: Have you learned any traditional techniques (such as forms of weaving) directly from craftspeople anywhere in the world? What stuck with you/struck you about their process, about their approach or way of seeing, even if your encounter was only through books?

Chris: Years ago when I was making shelters and baskets, I was doing this because I felt the need to go back to very basic principles and the first human need after food is shelter. The first human containers for collecting, carrying and storing food and water were woven baskets. Ceramics probably came about from a clay-covered basket being left in a fire. So although I did pick the brains of local basket makers, their craft was quite sophisticated in that it used willow grown especially for this. What I needed was a way of making a container from any plant material which I found along the way, because at this time I was walking in wild places where I would stop in some amazing place in an exhilarating time and make a basic shelter out of whatever material was prevalent in that place.

If I was going to use stone, for instance, it had to be right there to hand, even having to carry it more than 10 meters was too far. At the same time I would pick a bunch of plant material and carry that in the rucksack to be made into a basket at a later date. I discovered by trial and error that the easiest way to do this was to make a coil basket, which is in fact the oldest form. It needs any plant material for a stuffing and a material which won’t split or break to wrap around it. So I would test various sticks and grasses by wrapping them around my finger. This practice of using materials to hand created a sound principle which I later applied to commissioned works for particular sites. Material and shape had to be of the place, easily and cheaply available and not transported long distances. In theory this never precluded man-made materials because we are a part of it all, we are every bit as much nature as is a stick or a stone.

One of the basic underlying factors to all of this work was the repetitive task, using repeated movements both with the hands and with the body. To start with, walking day after day is an extraordinary thing to do. The continual movement of the physical body makes the mind very clear. It is not a meditation, thought is very much part of it, but thought is focused because the primary need when you are walking alone in wild places is to stay found and alive. In the same way, a repetitive task with the hands, day after day also focuses the mind. This includes weaving, hand-writing, printing and even some tasks on a computer. The Finnish architect, Juhani Pallasmaa, wrote two books called The Eyes of the Skin and The Thinking Hand about embodied thinking, where thought arises from the whole being, not just the mind.

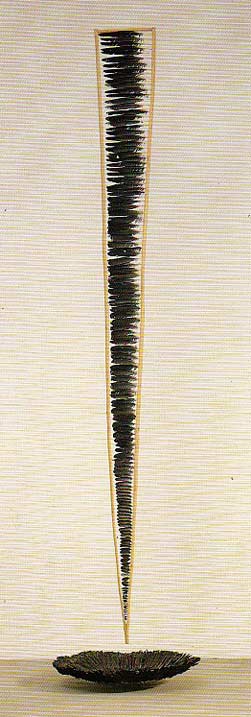

Ultimately, these early baskets later became large outdoor woven installation with Covered Cairn, Vortex, and Redwood Vortex, and in the growing works Time Capsule and Willow Domes on the Este. In some cases, baskets got enlarged and turned upside down to become shelter installations or even Cloud Chambers. What had once been repetitive hand movements became a movement of the whole body, often at the very limits of my strength.

Actually, one of the oldest crafts that I have often employed outside is dry stone wall making. I once asked an dry-stone builder who was repairing an ancient fort what the secret was. He replied, “Well, you put one stone on top of two stones and two stones on top of one stone.” I could have asked a bricklayer the same question but it is a little bit more complicated than that as it takes intense concentration over long periods to see the shape of stones and know which stone will fit where and do that at speed. It is compelling work and not easy particularly as the stones are often very heavy. At one point I worked with an old waller in Lancashire, who as a boy had knocked down a farmer’s wall, watching the stones roll down the hill. When the farmer complained to the boy’s father, he was made to carry the stones back up the hill and rebuild the wall and he just kept building, for the rest of his life.

When you start to turn a wall into a beehive hut you are repeating a process begun in prehistoric times, where not only does one stone have to sit on two, it has to come in a bit on each row, tie into the back with a through stone, follow the curve of the wall, pack in very tight and every now and then a long stone has to stick out the back so you can climb the building as you make it. As you come up the wall which is slowly leaning in, the whole thing is precarious until it is capped with the big flat cap stone at the top. You can’t make a corbelled hut with granite, you need the long flat sedimentary sand stones. I learned all this by trial and error because no modern day dry-stone waller has made such a thing, but if you show them the principle, then any good waller can do it.

MS: In thinking of this patterns in material made by repeating movements of a craft, what older patterns have you seen anew through scientific instruments?

Chris: All of those universal patterns which you see in nature and also in art – the spiral (Nazca Lines), the whirlwind (native baskets of the southern states), the tree, the wave (Hokusai) etc, you can also see in the imaging processes of science, from medicine to particle physics. The echogram images revealing the 900,000 years of the build-up of ice in Antarctica, echo the rings found in the cross-sections of a trunk of an ancient tree. Fingerprints echo vortex patterns and are the macrocosmic equivalent of the pattern seen through microscopes of the nerve endings in the skin of our fingers.  (Fingerprint)

(Fingerprint)

MS: This idea of pattern comes together with the sense of your work as what you have said of some land artists “private rituals in the landscape.” There is a fun book, The Artful Universe, by Sanskrit scholar William K. Mahoney that looks at Vedic ritual as a form of aesthetics and poetics. Early on, he examines a key word ṛta, an idea similar to the Chinese tao, but often translated as universal law. And, interestingly for your connection-making artwork, it also means something “properly joined.” In thinking of your interest in flow patterns, Mahoney offers something that fits with your works’ resonant structures: “Ṛta is that hidden structure on which the divine, physical, and moral worlds are founded, through which they are inextricably connected and by which they are sustained.” He goes on to say:

“It may be of interest to note that the word ṛta is a distant relative not only of the English rite and thus ritual (both of which signify actions that lend or establish dramatic order to the disorder of life as it is often experienced) but also of the English harmony as well as of art and thus of artful.”

He later introduces a word, loka, which means “world,” and yet is interestingly traced to the idea of a clearing, a place to see clearly, in the forest or jungle. He speaks of how the rituals created new realms or worlds, and that “To reside in a loka was…to live where once could see things as they truly are. In other words, to establish a loka was to form a systematic and meaningful “world”…to locate onself in a cosmos, to find a locus of being within the chaos of existence.”

All of this feels like your work, the rightness (ha, ṛta-ness) of the work, the way your art seems to rise up out of the landscape. Your shelters and cairns come to mind and the woven spheres. This articulation of place is the heart of your work. And it feels like this happens because you know how to listen, how to not impose yourself but rather to allow the place to come through. This is a different orientation than the artist-as-individual asserting themselves in the landscape, transposing their vision, but more of an attentive participation with the place itself. Can you say more about this process of making the essence of the place visible, of participating in the landscape?

Chris: When I first went to Japan, to the mountainous rural areas of Kochi province on Shikoku Island, I found the whole culture so very other and different that my way of orienting myself was to go straight into nature and play with it and react to it. I made several simple works very quickly in the first three days by balancing and moving stones. During these three days I made the work Stone Whirlpool, by instinctively rearranging the small flat river stones on a shingle bank close to a waterfall. The whirlpool was in my mind at the time because on the flight over, in an in-flight magazine, I had noticed an image of a whirlpool taken from Sensitive Chaos. It was the swirling vortices of water under the waterfall which triggered the memory and made me start moving stones. This was in fact a key piece and later lead to all those vortex works in hospital courtyards, Echoes of the Heart and Rivers of Stone, as well as the big whirlpool pieces, Carbon Sink, etc.

So it is this process of instinctive inter-reaction with place and materials, coupled with a subliminal thought process, which gives rise to something new, which is, as we know, a reworking of the old.

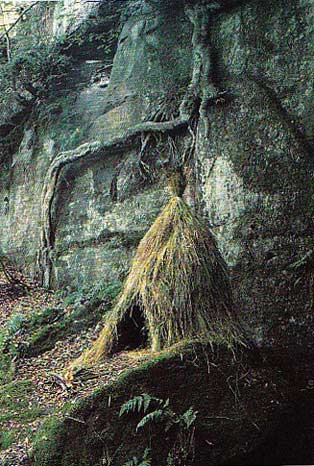

There are many instances of this. When I returned to a different area of Kochi the following year, I came with a few preconceived ideas – a big mistake. I found this incredible site on an abandoned track, cut into the side of a cliff above a rushing mountain torrent; a sensational place which was very alive. For several days I tried to weave bamboo into a shape it wouldn’t twist into. I was trying to use techniques which work with hazel but seemingly not with split bamboo. In frustration I told everyone to stop and let me have a morning just to think.

As I sat quietly in that place, I realized that the shape of the track with its overhanging rock was like an open-sided spherical tunnel and what it needed inside within it was a sphere, not a cone. So we quickly made five spheres in descending diameters from plant materials to hand (Shimanto River Spheres). The ginko trees were at that moment turning an extraordinary chrome yellow and falling from the trees, so school children collected them and we filled the big bamboo sphere with this incredible colour. Later a man took me aside and asked to take me to see something. He took me to a local Shinto Shrine where at the gate stood two huge organic stone spheres which had been taken from that very river. These limestone boulders had natural cups carved into them by water and were acting as wash basins for pilgrims entering the shrine. “This is why you have used spheres,” he said.

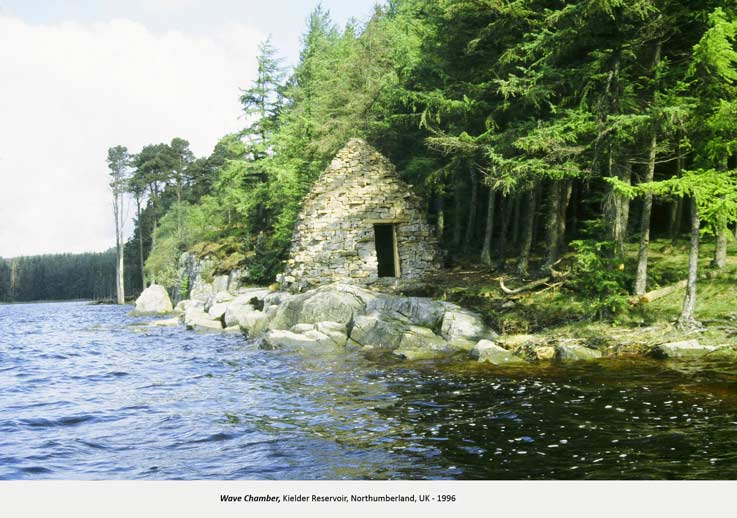

When I was commissioned to make a work on Kielder Reservoir in Northumberland, I was taken to a high point overlooking this vast ribbon of water. From here I could see on the opposite shore what looked like a small rock cliff above the lake, with trees coming right to the edge. This looked like a great place and so it turned out to be. It was an area where before the village was inundated by this man-made lake, people used to rock climb on these cliffs, and now, whatever the depth of the water at the time, there was always deep water at this spot. It was also quite a walk to get there. There were strong winds coming off the hills onto the lake and whipping the water up into big waves. At the same time I discovered that there were many large flagstones on the shorelines with wave patterns on them, the remnants of very ancient beaches. I had the idea of making a stone chamber on the edge of the water, with a floor of ancient wave patterns – a wave chamber. However, it was not until I saw a work using a lens set into the side of a container in Copenhagen Harbour that I began to have the germ of an idea of projecting the image of actual waves onto the floor of the chamber. It took a phone conversation with an optics company in Cambridge to find out how to do this by means of a simple periscope built into the top with a mirror angled at the lake and a lens beneath it to project that mirrored image onto the floor – and so an idea came to fruition.

There are so many instances of this over a lifetime of making works in place, that I could go on forever. The lesson I have learned is first to empty the mind and then to react to the place itself. Often with a big commission I will get a brief site visit and I don’t have long to make up my mind. Last year when doing a site visit at Chaumont on the River Loire in France, I had just one day and it rained so hard on that day it was impossible to get out and think straight. In the last hour of the evening the rain stopped and the sun came out. During my wanderings over the very extensive park within this hour I noticed a big circular clump of cedar trees with an expanse of grass lawn beside it. Instinctively I felt that the circle of trees should be echoed with another flat circle beside it, and that there was a feeling of entropy here, of trees dying and carbon going down into the earth to regenerate as energy in another time. So in that hour the idea of tree trunks moving out of the circle of trees into a whirlpool and down into the earth was born – Carbon Pool.

MS: Have you encountered that kind of strong sense of the place coming through elsewhere, as you did with the water sphere in Japan?

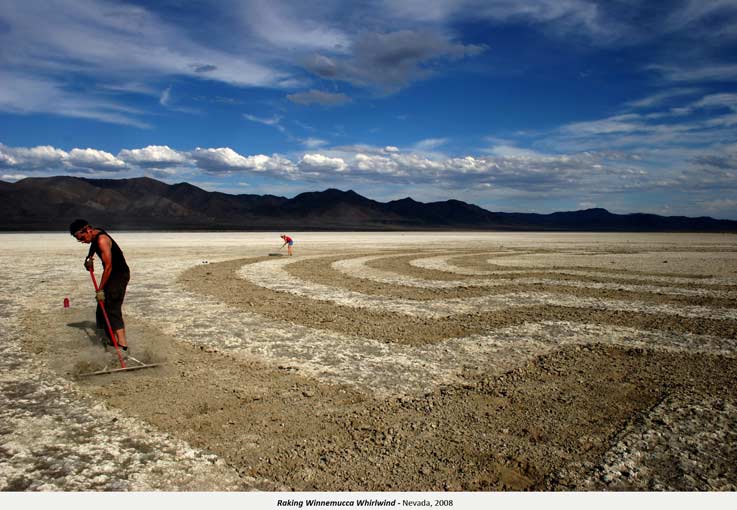

Chris: In every situation, in every place this has been so. I can’t think of a time or place where this hasn’t happened, even working in central London. In Nevada, when we were making the big whirlwind drawing on the dry playa of Lake Winnemucca on Paiute land, it was June and at the start it took us till midday to work out where to place the work and how big it could be. By that time it was very hot and the reflected heat coming off the white saltpan was like an oven. The three of us were in danger of succumbing to heat stroke. Somebody remarked that there would be a full moon that night so we returned at sunset and raked throughout the night in the eerily beautiful moonlight. It took us 18 hours to complete.

The following day we returned in the evening to take photographs with the sun behind us illuminating the drawing. As we did so, big black clouds blew in and not long after the images were in the bag, it rained and the drawing sank back into the playa. A month later the Museum sent a crew out to re-rake it so visitors to the show could go out into the desert to experience it first-hand. Exactly the same thing happened, it poured with rain and the drawing disappeared again. Two years after the show came down, someone passing on the road noticed that the drawing had faintly reappeared and they sent me an image. The one thing about this drawing was that it was exceptionally hard work as before each pull of the rake you had to smash down to break the crust. It was a repetitive, whole body task but mind-numbingly hard and we were all relieved when it was done. But then that is often the case: it is only with hindsight that you realize what a magical thing it was to do.

MS: How does weaving or building help to de-center the self-as-center yet center or ground you in the space?

Chris: In a sense because they are mindless, all repetitive tasks de-centre the self because the focus is elsewhere and we are focusing on hand and body movements. I guess Yoga does the same. Repetitive tasks don’t necessarily ground you in space, however: if I am working in a studio I will also have some kind of talk radio on, but outside, building, weaving, using your whole body – that really does ground you in space.

MS: You mention being moved by Uluru and of course by the Anarctic. Can you say more about either place? What words come for the arctic, in this time when we are bringing about its ending?

Chris: People tell me of a time when you could wander at will on your own and bathe in the rock pools at Uluru, but now has been totally wrecked by the tourist industry, with people climbing it although it is a sacred shrine. Despite all this, it still retains a quite shocking presence. You can stand along with the many hundreds of tourists at sunset and as that enormous ancient geological deposit glows red in the dying sun, the world seems to stop. It is the same at the Olgas. The Antarctic is so beautiful it makes you weep. Sometimes when there is a wind and the sun is shining it is like walking through gold dust, because of the ice particles in the air. There were times when we all just leapt into the air for the sheer joy of just being there. It was also a hard and quite lonely place to be, and in the interior there is no life at all. Parts of Antarctica are getting colder, but the sea is warming and the ice shelves are melting. The more they melt the faster the glaciers move so in time, a long time, the glaciers will literally slide off.

MS: What other places have been powerful for you?

Chris: Too many to list, but suffice to say that all places which have not been ruined by man have something special about them. The only place I know where man has had a totally positive effect on the terrain is in Ladakh, where people have built irrigation channels to take snow melt run-off, so when you come across a village in the brown mountain desert, it shimmers an iridescent green and you can smell herbs and flowers.

MS: Where are you now, and what is striking you about the place you are in today?

Chris: I live in south-east England, an ancient land which has been farmed for thousands of years and over that time man has also had a positive effect on this land and it too is very beautiful. Just now my wife, the poet and novelist Kay Syrad, and I have been engaged in a project commissioned by Cape Farewell involving three farms in Dorset – Thomas Hardy country, three hours’ drive west of our home in Sussex, and still a part of the southern chalk landscape. Over a year we have been getting to know the farmers and their relationship with the land. Two of the farms are organic dairy and the third is a sheep farm under a Government environmental stewardship scheme. The landscape is beautiful in its quiet way but what is more interesting is the cycle of interdependence between, man, animal and landscape and the surprising simplicity of producing food in a sustainable way. The work of these farms shows how it is possible for us all to eat well without destroying the planet, which is our home. I will also be making a thatched cloud chamber on one of the farms next year.

MS: We are living in a culture/time that tends to be anesthetized to nature, to see it in terms of utility. Ecocritic Greg Garrard noted that the prevailing vision in terms of nature is to see things as “gravel for our parking lots” (or pretty stone for our counter tops). Your aesthetics wakes us up; your works made of clay and blood, of willow and hazel wood, reconnect us with the raw power of materials, the inherent “skill,” if you will, of matter—a kind of “genius” within the matter. Part of the power in your works comes from what feels like a finely tuned practice of setting yourself aside and letting the material lead, and what comes of this listening to the material is an essence of a place or even of a wild thing, such as with the marvelous Basket for the Crows—which feels like it encapsulates the playfulness and power of “crowness.”

What material(s) do you find most beguiling to work with? What material has been most difficult for you to find your way within? What material remains a question, a koan? Is there a material you have not yet begun to work with but wonder about?

Chris: I have never had a problem with any material because once a material has revealed itself then that is the right material in the right place at the right time and it is the nature of that material that dictates just how you use it. The material we will be using on the farm for the cloud chamber next year is flint and lime mortar for the walls, because it is there and there is the knowledge how to make a flint wall. We will line this with chalk blocks to make the interior white to take the projected image. There is a barn nearby which is built of hand-cut chalk blocks but our problem will be sourcing that locally today. The work will sit within a depression or bowl in the side of the hill from which chalk has been taken in the past to make a clay field less acid to grow corn. So the shape of the chamber will be upturned bowl-like and will be roofed with thatch, because one of the organic farmers grows an ancient corn with a strong stalk (Maris Widgeon), that he stooks and sells the stalk on to thatchers to thatch many of the houses around there. That particular corn makes a very good roof, so we will use a local thatcher to do the work with material grown half a mile away.

That is the kind of process that I use every time. Mostly I have no idea, when I start, what material I will use, but by the end I will have learned something new and that is what is important. I guess that is the Koan.

In 1993, I wrote this, which seems to fit:

“The thing is not the thing.

The thing points to the thing.

Sometimes the thing points to the

thing which points to the thing.

The thing is in movement.

These words are not the thing.”

MS: In introducing your work, I spoke of seeing art in the natural configurations of stones and branches. Your work has a light touch; it feels of the land. I think of dancer/improviser/writer Miranda Tufnell’s observation that when we see pleasing forms in nature, such as animal footprints in the snow, we see traces of a living process. Your work has that quality. And it allows for weather, time and decay, Ezra Pound’s “the wind is part of the process/the rain is part of the process.” What is it like to work with time as a material, as you have done with your work with trees?

Chris: You always work with time unless you are a particle physicist. As I get older I tend to want to make things which will last into a foreseeable future. But all things have their time; some things are all the more beautiful for being ephemeral. But even if something is built with stone, it will have an allotted time-space. Remember the patient proto-bacteria in Antarctica, waiting for a warmer climate to break down rock, to create soil to grow a forest. However, making a work which will grow and change is an interesting thing to do. I have made five or six of these works, and what I have learned is that you cannot predict how they will turn out, because they depend entirely on a relationship with people down the years. If the work is neglected, it will rapidly die or go back to scrub. Man always has to be a part of the equation.

Two of these works, one at the South Carolina Botanical Garden in Clemson (Time Capsule) and the other in the well-tended grounds of the University of Australia in Canberra (The Way of Trees, Earth and Water), are well looked after by the respective organizations. Heart of Reeds is looked after as a work of biodiversity by Lewes District Council, and in Germany my two works, Willow Domes on the Este and Equinox, are tended each year and so are growing very well. The process is a delicate dance between man and nature, where man has to be mindful of what the work needs. That may in itself be unpredictable.

MS: In the clamor towards the next classification, the next idea, we’ve arrived at “post-nature” and “post-human,” ideas that can be used for help or harm. And yet, it seems sad to be rushing towards post-nature and post-human before we have even the faintest understanding of the complexity of what these are. Perhaps we are post-human in that we don’t know how to see in; post-nature in that we don’t know how to see out.

You create spaces that help us remember ourselves in these ways, places to come to our senses, senses we have forgotten we have. In terms of helping us get to know our insides and the outside at the same time, your cloud chambers give us places to look inside, while the outside is projected within through a pinhole camera in a soft impressionistic image rather like a dream. You have created tipi-like shelters and stayed within in them, meditatively, marking the hours there. One form you often work with is temporary shelters made of the branches and grasses, the moss and stone of the place you are in. Some are rather like sweatlodges in appearance. Your shelters for nonhuman entities such as “shelter for the northern glaciers” and “shelter for the forest deer” point to fragility of these presences in a time when humanity is changing the landscape and climate.

How does this quiet call to wake up fit with your artists’ statement below? Would you speak to the final five lines in particular? What do they mean when the idea of nature as a manmade term, is happening alongside the displacement of nature with more parking lots? What do they mean when the culture has become toxic? And how do these last five lines play out in your work?

Chris: “Culture is the veil through which we describe nature.”

Culture is our conditioning, from how we are brought up as kids to how our society is conditioned to act out in the world. Nature simply “is”, but nature is a word from culture so it becomes language. Culture isn’t the ‘isness’ of nature, it is how we are conditioned to see and experience it. It is the veil through which we view the world.

“The process of nature continues despite our analysis.”

So we analyze it with thought and language and all the time nature just gets on with it.

“Our analysis is part of the process of nature.” Since we too are nature, as you say – made of stardust, then the working of our brains is part of the process of nature.

“The process of nature must include the actions of man”

As it surely does.

“whether or not they are destructive.”

Which it certainly is ..

“Man’s description of ‘nature’ as something separate –

out of town – where the edge is the division

between ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, is an illusion.

‘Nature’ and ‘culture’ are the same thing.

There is no division.”

The trouble is we see ourselves as something separate and we are not. That is the illusion of self, of language and culture. In language, nature and culture are the same thing as they arise from the same process – thought. It is only when we see that and go beyond it, can we really be nature. But that nature, especially when it is caught in thought and ego, is very destructive. But the Universe created us and it may just be the way that our living earth lives and evolves and perhaps dies, although some other living entity will surely take our place. We are caught in a universal process of entropy and the Universe is still exhaling. However that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t live meaningful and sustainable lives.

With respect to my own work, it is all overshadowed by the veil: it is culture. However it very often arises through intuition and instinct; from not thinking, from the body mind. That first instinctive reaction then gets translated through thought and knowledge (culture), into art.

MS: You recently put together a retrospective of some of your work in Norway. What struck you most looking back at your work over the years—did you notice any formal aspect of it that you had not seen before?

Chris: One of the difficulties dealers and curators have with my work is that it seems unpredictable and eclectic. It isn’t obvious that there is one particular strand that runs through it. What I have always said is that what I do does not have one particular style, method, material or form, rather it uses what is appropriate to time and place, and this might be very different from show to show. But looking back over the years, as I did in Norway with a small archival room, I noticed that there is a clear trajectory to the work, a very consistent interest in Nature/Culture, Inner/Outer and Micro/Macro. This interest takes different forms but here too is a great consistency – shelters, baskets and bundles linked to walking in landscapes, inner and outer (seen particularly in cloud chambers) and the microcosm and macrocosm seen though all of the work to do with systems in the body and on the planet. I would add to that cycles of life, death and regeneration represented by the mushroom.

MS: The Carbon Sink piece that the big-money coal executives revoked from the grounds of the University of Wyoming in 2012 brings to the foreground the idea of “rival minds” and “rival visions for society” that Hugh Brody talks about in his book about Inuit perceptions and ways of living, The Other Side of Eden. This clash of minds/social visions, determines how we see and what we make of this life here with nature and with others: Whether we tend to see things and others as always involving our own personal gain, and that filter in turn always involving competition and territory and threat. Or whether we see things in ways very different than all that….You have mentioned an upcoming project involving uranium mines in Australia. What is the issue at stake? What form might this project take? How will you collaborate with the community there? Is this the first time you will have worked closely with people who uphold indigenous culture?

Chris: In 2013 I gave a lecture in Denmark about the South Western coast of Australia, among the vast eucalypt forests, and then took a trip up to the desert north of Kalgoorlie to meet Kado Muir, an aboriginal elder involved in protesting against uranium mining on native lands. Kado explained the importance of land and ancestors and sacred sites to his people, and how it is their job to care for that land, whilst the mining companies, on whom the local communities depend for work, are digging up yellow cake and exporting it to countries all over the world who were using it to make weapons that would kill people and energy that would pollute other lands. Their feelings of duty, of care for people and land were completely in conflict with this. He also explained the water serpent myth of his people, which mirrors the geographical fact of the centre of Australia once being a vast inland sea. If you pollute that ground water now, then cities like Adelaide, Perth and Melbourne, which are all connected by that underground sea, will also be affected in time, to say nothing of the people who will have nuclear bombs dropped on them.

We talked about making a Mushroom Cloud work using suspended objects from the desert and doing that in cities, but really it was Kado who was creating a living, breathing political art form by arranging a yearly ‘Walk for Country’, which took place over several weeks each autumn. Here people from all walks of life, his own community and from around the world would gather at the mining site and would walk though the desert to Leonora. They traveled at the pace of the slowest, with children and the elderly taking part, and during this slow walk through country, the country itself would enter the spirit of those people and the whole ethos of caring for land would be embodied.

This of course, goes radically further than any thing that I might propose – and it doesn’t need funding. They just do it. Much as I would like to contribute, I think that maybe it is superfluous unless some unforeseen set of circumstances intervenes.

I’ve learnt from all my experience of working with indigenous native peoples, including the Paiute in Nevada, that you have to be very sensitive to a community’s deep-rooted sense of who they are and how they belong. Most often, these peoples have been treated to genocide in the past and their culture has been ignored and trashed – even by artists. Incredibly careful and respectful exchanges need to take place before a site is selected, for example. Anthony Gormley’s work, Inside Australia at Lake Ballard, a stone’s throw from Leonora, is a case in point. Despite the assistance of Hugh Brody in negotiating with the indigenous peoples of the area, the women elders were not consulted, and a very male work was installed on a women’s sacred site known as the Seven Sisters.

MS: You are also beginning to do work with organic farms in the UK. You’ve done some prints of plants from these farms—can you say more about what other work you are doing with the farms? What kind of collaboration—and learning—is happening with the farmers and the communities around the farms?

Chris: The Cape Farewell project that I mentioned earlier is called Exchange, and we would ideally like the exhibition to travel around various old corn exchange buildings in England. After a year of research we are close now to completing a hand-made book and a collection of works on paper which map our year and theirs. We have really needed those farmers to give us a picture of their way of life and underlying philosophy. Without their cooperation we could not have done the work. As such this is a collaboration and hopefully a little of the importance and poetry of what they do will be communicated further afield.

I have been making portraits of the farmers, layering their own hand-written statements over black and white images, to produce portrait images of them made up of their own words. You can’t read the words because they are reduced to a scribble, but there is a kind of homeopathic exchange between their image and their thinking.

I’ve also made a work which comprises woven maps of the area, fingerprints in soil pigment and weather patterns in the macrocosm; and the main work is a large (A2) hand-made artist’s book which attempts to encapsulate the work of the farmers, soil, plants, animals and food. The visual element is complex. We buried 100 sheets of A1 artists 300 gm paper in the soil of one of the farms for 10 months. We then dug up a square cubit of turf from one of the fields on the escarpment close to a site of special scientific interest. From this turf I took 60 plants, or clumps of plants, scanned them and then mono-printed them onto the formerly buried paper. I did that by printing the plant image (in duotone) onto the smooth side of OHP acetate, wetting the paper and then transferring the image by rolling the back of the acetate. What you get is an image like a very subtle drawing – almost dreamlike, on this amazing mottled and earthy paper. These 60 images are interspersed with 60 pages of text by Kay Syrad, which is part poem, part quotation, part list, part breakdown of the minutiae of farm work – all of which goes towards creating the organic food they produce and the bio-diverse landscape in which the community live.

I will be returning next year to make a cloud chamber, close to the place where the cubit of turf was dug up and this will involve more of the local expertise in the area. This is something I am very much looking forward to doing next year.

MS: What project(s) are you currently most excited about beginning?

Chris: I intend to write a book about encounters I’ve had with people and animals in the many different cultures and wild places that I have found myself in over my working life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.