On Monday, November 26, I returned to work from the long holiday weekend and found in my inbox an email from Dennis Doros, AMIA Board President, notifying me that they were suddenly and unexpectedly without a keynote speaker for the upcoming AMIA conference in Portland, OR. They very kindly asked if I wanted to step in and deliver some remarks to my colleagues that Thursday morning instead. This conference was deeply meaningful to me — AMIA has been my must-go professional gathering since the first time I attended in 2001, and it happens that my very first AMIA was also held in Portland. Seventeen years later, I was being offered the chance to return as director of the MLIS degree program I’d only just graduated from back in 2001, and to deliver a speech that would help welcome a new generation of students and first-time attendees as warmly as I was welcomed then (by colleagues like Stephen Parr, Bill O’Farrell, Sam Kula, and Alan Stark, all of whom are sadly no longer with us). I said yes, of course, and delivered the following remarks — which might have been longer, but not necessarily better or more heartfelt, had I more time to prepare them.

*

Transcending the national: Some thoughts on becoming a community of practice

As I think most of you know, Fackson Banda couldn’t be here today, as originally scheduled, because of visa issues and international travel restrictions. On Friday afternoon, during the Further Freaky Film Formats session, I’ll be pinch-hitting for another colleague, Stefanie Zingl from the Austrian Film Museum.

She had hoped to be here to speak about the short-lived Mroz Farbenfilm technology, but her application for travel funding was approved only last week—too late for her to make arrangements to attend in person. It’s upsetting when these things happen, because these people are part of our professional community. Their voices are the ones we wanted to hear this week—not mine, speaking in their place. The imposition of other regimes—geographical, bureaucratic, political, or financial—on their ability to come home to us feels wrong.

Communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.

– Etienne Wenger (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction.

The regular interaction with others to deepen our knowledge and broaden our perspectives on areas of shared concern is a definitive aspect of the community of practice. Our own Ray Edmondson, who will be deservedly honored this week with AMIA’s first Advocacy Award for his decades of work to unite the global community of media archivists, also touched on this in his consideration of us as a profession.

A profession is a field of remunerative work which involves university level training and preparation, has a sense of vocation or long term commitment, involves distinctive skills and expertise, worldview, standards and ethics. It implies continuing development of its defining knowledge base, and of its individual practitioners.

-Edmondson, R. (1995). Is Film Archiving a Profession?

Film History, 7(3), 245–255.

And Terry Cook may have put it best and most succinctly when he spoke of archives, and the archive, as a foreign country. At times like this, when geopolitical boundaries are encroaching on our archival ones, I especially feel the truth of this—that we are a nation unto ourselves, and negotiating our sovereignty.

The archive(s) is a foreign country.

Cook, T. (2011). The Archive(s) Is a Foreign Country:

Historians, Archivists, and the Changing Archival Landscape.

The American Archivist, 74(2), 600–632.

I am confident that the folks in this room who have taken my Intro to Media Archiving and Preservation class at UCLA will also have picked up on the reference in the title of my talk to Caroline Frick’s book Saving Cinema. But even if you didn’t do the assigned readings (and yeah, I know who you are), you can see that the unit of observation in her account of film preservation’s social and political history is the nation.  As I thought about what I would want to say in this venue, and how national origin and being from somewhere in particular is one of the things that still dictates whether or not one could participate in our community of practice, it seemed the me that we are, together, writing a new chapter in this history. We may be trying to move beyond the national, or perhaps to become a nation of our own—not foreign, as Cook would have it, but familiar, and familial.

As I thought about what I would want to say in this venue, and how national origin and being from somewhere in particular is one of the things that still dictates whether or not one could participate in our community of practice, it seemed the me that we are, together, writing a new chapter in this history. We may be trying to move beyond the national, or perhaps to become a nation of our own—not foreign, as Cook would have it, but familiar, and familial.

So let’s look at what makes a nation: Language. Culture. Shared history. Systems of governance and social order. A common currency and a shared identity. And a national anthem, which I think it’s safe to say we now have!

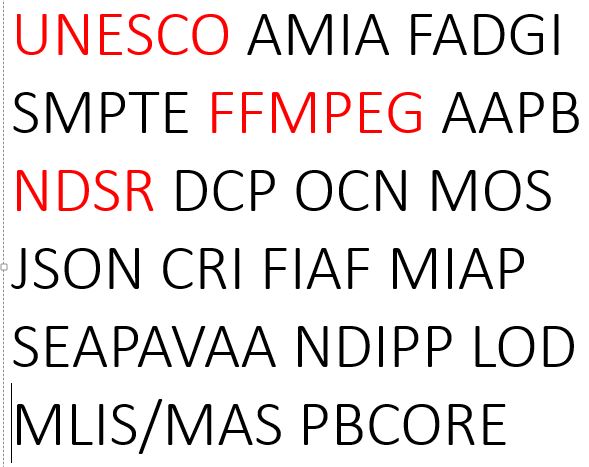

As to language: We speak our own. To the uninitiated, it is a Babel dialect comprising mainly acronyms and words with all the vowels taken out. Is this Hebrew? Or Italian? or Welsh? (Come on, ffmpeg has to be Welsh for something.) The only way to really learn it is through immersion, it seems, and like all languages, it’s evolving and changing all the time. Whether or not they did the readings in my class, I think every media preservation student I’ve taught will remember my insistence that they be conscientious in their use of the words “film” and “video”—which are so often used indiscriminately, and whose specificity are really important in the context of our work with moving images. And these images do move, across and around the world!

Here in the U.S., our own National Film Preservation Foundation has repatriated American films from all over the globe, through collaborative efforts with the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, Nga Taonga Sound & Vision in New Zealand, and the EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam. And last year’s feature screening at AMIA, Bill Morrison’s Dawson City: Frozen Time, documented the Yukon Territory film find that had already become legendary by the time I attended my first AMIA conference back in 2001.

But when I think about how these images move, I also think of home movies—many of which were, paradoxically, shot far away from home, by vacationers and missionaries, emigres and refugees, over the last century or so. Projects like the international Home Movie Day event and the work of regional archives that collect home movies and amateur films have helped us see that the “home” in home movies refers not to our domestic environments, but to our home planet, this earth where we live. We are most at home in the foreign country that is this archive.

We are also citizens of a land where time matters both a lot less and a lot more than the rest of the world. Our work bridges the past and the present; I like to say that film archivists have one foot in the 19th century and on foot in the 22nd. In fact, the technologies we use today have their roots in not just photography, but the artistic experiments of the 16th century, and the scientific advances of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the optical toys of the 19th, and ideas like neuroscience that emerged in the 20th.

The critical affordances of all of these earlier media and tools of creation and understanding reverberate in the digital capture, storage, manipulation, and transmission methods we use today, and are working to preserve into the next century.

As we do so, we sometimes exceed our own boundaries. Our knowledge of what to do and how to do it, while always growing, is necessarily incomplete. Venues like the Orphan Film Symposium and the Bastard Film Encounter are where we consciously explore no-man’s land—try to decide what to do when our maps and methods are insufficient for dealing with the materials we encounter in our collections. We can—and do—take pictures of everything. Must we save it all? The exploitative pornography, the documentation of experiments on animals? The creepy footage of women’s feet and the Army’s “dental cripples” and developmentally disabled children—all shot without their knowledge or consent and then shared (in the latter cases, at least) with audiences of medical professionals? What about the inscrutable, taped-off-the-television VHS compilations of a queer teenager, growing up closeted and confused in the Midwest? The myriad fragments of censored material that someone put on a reel a long time ago, and that just seem innocuous now? What about the merely mediocre and the entirely too typical? What laws govern the nation where material like this comprises the national cinema? We’re still figuring this out, and we’re doing so as a community of practice.

Connecting is easier in a networked world. That’s as true for our data, our shared standards and descriptive practices, as it is on a human level. And that is a major argument for us to continue strengthening our capacity to allow virtual presence and telepresence. AMIA wasn’t the only organization that struggled this year with unexpected difficulties getting scheduled speakers to where their conference was being held.

But part of why we are here today because we also, and still, value being in one another’s actual presence. We value the ability to touch the same object with our hands that someone else touched with theirs. We value the act of eating a meal together, of raising our glasses in a toast to one another. We revel, too, in digging through the trash for the things that can still be salvaged; in fact, you might call that our national pastime. And of all people, we are the people who most understand the power of sitting together quietly in the darkness, our eyes all turned to the bright light we see before us. My country, tis of thee! We are AMIA, and in the words of our new national anthem, we are saving the world one frame at a time.